History & Criticism

- Publisher : Biblioasis

- Published : 01 Jun 2021

- Pages : 336

- ISBN-10 : 1771964111

- ISBN-13 : 9781771964111

- Language : English

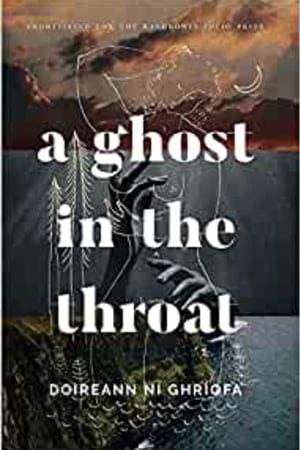

A Ghost in the Throat

An Post Irish Book Awards Nonfiction Book of the Year • A Guardian Best Book of 2020 • Shortlisted for the 2021 Rathbones Folio Prize • Longlisted for the 2021 Republic of Consciousness Prize • Winner of the James Tait Black Biography Prize • A New York Times New & Noteworthy Title • Longlisted for the 2021 Gordon Burn Prize • A Buzzfeed Recommended Summer Read • A Publishers Weekly Best Book of 2021 • A Book Riot Best Book of 2022 • An NPR Best Book of 2021 • A Chicago Public Library Best Book of 2021 • A Globe and Mail Book of the Year • A Winnipeg Free Press Top Read of 2021 • An Entropy Magazine Best of the Year • A LitHub Best Book of 2021 • A New York Times Critics' Top Book of 2021 • A National Book Critics Circle Award Finalist

When we first met, I was a child, and she had been dead for centuries.

On discovering her murdered husband's body, an eighteenth-century Irish noblewoman drinks handfuls of his blood and composes an extraordinary lament. Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill's poem travels through the centuries, finding its way to a new mother who has narrowly avoided her own fatal tragedy. When she realizes that the literature dedicated to the poem reduces Eibhlín Dubh's life to flimsy sketches, she wants more: the details of the poet's girlhood and old age; her unique rages, joys, sorrows, and desires; the shape of her days and site of her final place of rest. What follows is an adventure in which Doireann Ní Ghríofa sets out to discover Eibhlín Dubh's erased life-and in doing so, discovers her own.

Moving fluidly between past and present, quest and elegy, poetry and those who make it, A Ghost in the Throat is a shapeshifting book: a record of literary obsession; a narrative about the erasure of a people, of a language, of women; a meditation on motherhood and on translation; and an unforgettable story about finding your voice by freeing another's.

When we first met, I was a child, and she had been dead for centuries.

On discovering her murdered husband's body, an eighteenth-century Irish noblewoman drinks handfuls of his blood and composes an extraordinary lament. Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill's poem travels through the centuries, finding its way to a new mother who has narrowly avoided her own fatal tragedy. When she realizes that the literature dedicated to the poem reduces Eibhlín Dubh's life to flimsy sketches, she wants more: the details of the poet's girlhood and old age; her unique rages, joys, sorrows, and desires; the shape of her days and site of her final place of rest. What follows is an adventure in which Doireann Ní Ghríofa sets out to discover Eibhlín Dubh's erased life-and in doing so, discovers her own.

Moving fluidly between past and present, quest and elegy, poetry and those who make it, A Ghost in the Throat is a shapeshifting book: a record of literary obsession; a narrative about the erasure of a people, of a language, of women; a meditation on motherhood and on translation; and an unforgettable story about finding your voice by freeing another's.

Editorial Reviews

Praise for A Ghost in the Throat

"The ardent, shape-shifting A Ghost in the Throat is Ní Ghríofa's offering ... She pieces together Ní Chonaill's life as if she is darning a hem, keeping the story from unraveling further. She interrupts herself to stuff a child into a car seat, wrestle a duvet into its cover, pick pieces of pasta off the floor ... What is this ecstasy of self-abnegation, what are its costs? She documents this tendency without shame or fear but with curiosity, even amusement ... The real woman Ní Ghríofa summons forth is herself."

-Parul Sehgal, New York Times

"A powerful, bewitching blend of memoir and literary investigation … Ní Ghríofa is deeply attuned to the gaps, silences and mysteries in women's lives, and the book reveals, perhaps above all else, how we absorb what we love-a child, a lover, a poem-and how it changes us from the inside out."

-Nina Maclaughlin, New York Times

"A Ghost in the Throat moves between past and present with hallucinogenic intensity as the narrator uncovers the details of the dead woman's life, each revelation deepening her own sense of herself as a writer and a woman and creating in the process a brave and beautiful work of art."

-Republic of Consciousness Prize

"Electrifying and genre-bending ... The book's title conveys the uncanny feeling Ní Ghríofa had while writing the book, of having another's voice emanate from her own throat ... Ní Ghríofa's quest sometimes feels like DNA-sleuthing, but with earth and texts taking the place of cheek swabs ... The final act of reciprocity may be that one great work has ultimately spawned another. Ní Ghríofa's book wouldn't exist without Ní Chonaill's poem, in the same way the poem wouldn't exist without the death of Art O'Leary: both are rooted in agonizing, exquisite emotion."

-Globe & Mail

"A detailed tapestry that threads Eibhlín Dubh's family histories with the author's own translations of her poem from the Irish, Ní Ghríofa's essayistic and intimate style recalls the inter-disciplinary perambulations of W.G. Sebald and the uncompromising feminism of Maggie Nelson ... A Ghost in the Throat is a kaleidoscopic book of 'homemaking' that centers the intuitive knowledge of the ...

"The ardent, shape-shifting A Ghost in the Throat is Ní Ghríofa's offering ... She pieces together Ní Chonaill's life as if she is darning a hem, keeping the story from unraveling further. She interrupts herself to stuff a child into a car seat, wrestle a duvet into its cover, pick pieces of pasta off the floor ... What is this ecstasy of self-abnegation, what are its costs? She documents this tendency without shame or fear but with curiosity, even amusement ... The real woman Ní Ghríofa summons forth is herself."

-Parul Sehgal, New York Times

"A powerful, bewitching blend of memoir and literary investigation … Ní Ghríofa is deeply attuned to the gaps, silences and mysteries in women's lives, and the book reveals, perhaps above all else, how we absorb what we love-a child, a lover, a poem-and how it changes us from the inside out."

-Nina Maclaughlin, New York Times

"A Ghost in the Throat moves between past and present with hallucinogenic intensity as the narrator uncovers the details of the dead woman's life, each revelation deepening her own sense of herself as a writer and a woman and creating in the process a brave and beautiful work of art."

-Republic of Consciousness Prize

"Electrifying and genre-bending ... The book's title conveys the uncanny feeling Ní Ghríofa had while writing the book, of having another's voice emanate from her own throat ... Ní Ghríofa's quest sometimes feels like DNA-sleuthing, but with earth and texts taking the place of cheek swabs ... The final act of reciprocity may be that one great work has ultimately spawned another. Ní Ghríofa's book wouldn't exist without Ní Chonaill's poem, in the same way the poem wouldn't exist without the death of Art O'Leary: both are rooted in agonizing, exquisite emotion."

-Globe & Mail

"A detailed tapestry that threads Eibhlín Dubh's family histories with the author's own translations of her poem from the Irish, Ní Ghríofa's essayistic and intimate style recalls the inter-disciplinary perambulations of W.G. Sebald and the uncompromising feminism of Maggie Nelson ... A Ghost in the Throat is a kaleidoscopic book of 'homemaking' that centers the intuitive knowledge of the ...

Readers Top Reviews

FisherwomanRaymond P

perhaps my favorite book of all time..so enthralling..so powerful, so alive...more awards for the author!!

Ethan Zlomke

What does it mean to be a woman? Doireann Ní Ghríofa interweaves the story of her translating an eighteenth century Irish poem with the subject of the poem. She tries to find a balance between being a mother and wife and woman with being an artist and scholar and begins to question whether balance is even possible. I dog-eared many, many pages to mark favorite passages. Highly recommended.

Gerald O'Malley

This is a very, very good book. A real celebration of female individuals and feminism. The author explores the origins of one of the most famous poems of the 18th century and the woman who wrote it. She sling-shots between 18th century and modern day Ireland drawing from her own experiences giving birth, breastfeeding and running a household full of men with that of the 18th century poet and mother. The author is a poet and frames her observations and comparisons of the female experience in remarkably colorful and creative ways, folding phrases and melting paragraphs into each other, uncovering truths and revealing secrets. Digging through centuries of birth records and cemetery tracings and hospital records and newspapers, the author's search for the fate of the 18th century poet is a sad story - an example of the literary tyranny of men and the ignoring of the vital sex. Ghost in the Throat is a remarkable achievement.

Zisi

Doireann Ní Ghoríofa's "A Ghost in the Throat," which parallels the lives of two Irish women Irish poets, one contemporary, the other 18th century. The work is an amalgam of autobiography, auto-fiction, and translation, but most of all is about the author's obsession with rescuing women erased from history or reduced to mere satellites by their husbands and male children. It is an extraordinary achievement, beautifully written.

Short Excerpt Teaser

The baby sleeps in a third-hand cot held together with black gaff tape, and the walls of our rented bedroom are decorated not with pastel murals, but with a constellation of black mould. I can never think of a lullaby, so I resort to tunes from teenage mixtapes instead. I used to rewind ‘Karma Police' so obsessively that I wondered whether the brown spool might snap, but every time I pressed play the machine gave me the song again. Now, in my exhaustion, I return to that melody, humming it gently as the baby glugs from my breast. Once his jaw relaxes and his eyes roll back, I creep away, struck again by how often moments of my day are lived by countless other women in countless other rooms, through the shared text of our days. I wonder whether they love their drudge-work as I do, whether they take the same joy in slowly erasing a list like mine, filled with such simplicities as:

School-run

Mop

Hoover Upstairs

Pump

Bins

Dishwasher

Laundry

Clean Toilets

Milk/Spinach/Chicken/Porridge

School-run

Bank + Playground

Dinner

Baths

Bedtime I keep my list as close as my phone, and draw a deep sense of satis- faction each time I strike a task from it. In such erasure lies joy. No matter how much I give of myself to household chores, each of the rooms under my control swiftly unravels itself again in my aftermath, as though a shadow hand were already beginning the unwritten lists of my tomorrows: more tidying, more hoovering, more dusting, more wiping and mopping and polishing. When my husband is home, we divide the chores, but when I'm alone, I work alone. I don't tell him, but I prefer it that way. I like to be in control. Despite all the chores on my list, and despite my devotion to their completion, the house looks as cheerily dishevelled as any other home of young children, no cleaner, no dirtier.

So far this morning, I have only crossed off school-run, a task which encompassed waking the children, dressing, washing, and feeding them, clearing the breakfast table, finding coats and hats and shoes, brushing teeth, shouting the word ‘shoes' several times, filling a lunchbox, checking a schoolbag, shouting for shoes again, and then, finally, walking to the school and back. Since returning home, I have still only half-filled the dishwasher, half-helped my son with his jigsaw, and half-mopped the floor – nothing worthy of deletion from my list. I cling to my list because it is this list which holds my hand through my days, breaking the hours into a series of small, achievable tasks. By the end of a good list, when I am held again in my sleeping husband's arms, this text has become a sequence of scribbles, an obliteration which I observe in joy and satisfaction, because the gradual erasure of this handwritten document makes me feel as though I have achieved some- thing of worth in my hours. The list is both my map and my compass.

Now I can feel myself starting to fall behind, so I skim the text of today's tasks to find my bearings, then set the dishwasher humming and draw a line through that word. I smile as I help the toddler find his missing jigsaw piece, clap when he completes it, and finally resort to the remote control. I don't cuddle him close as he watches The Octonauts. I don't sit on the sofa with him and close my weary eyes for ten minutes. Instead, I hurry to the kitchen, finish mopping, empty the bins, and then check those tasks off my list with a flourish.

At the sink I scrub my hands, nails, and wrists, then scrub them again. I lift sections of funnels and filters from the steam sterilizer to assemble my breastpump. These machines are not cheap and I no longer have a paying job, so I bought mine second-hand. On my screen, the ad seemed almost as poignant as the baby shoes story usually attributed to Ernest Hemingway –

Bought for €209, will sell for €45 ONO.

Used once. Every morning for months this machine and I have followed the same small ritual in order to gather milk for the babies of strangers. I unclip my bra and scoop my breast into the funnel. It's always the right breast, because my left breast is a lazy bastard: by a month post-partum it has all but given up, so both baby and machine must be fully served by the right. I press the switch, wince as it jerks my nipple awkwardly, adjust myself, and then twist the dial that controls the intensity with which the machine pulls the flesh. At first, the mechanism draws fast and firm, mimicking the baby's pattern of quick suck, until it believes that the milk must have begun to emerge. After a moment or two the pump settles into a steady cadence: long tug, release, repeat. The sensation at nipple level is like a series o...

School-run

Mop

Hoover Upstairs

Pump

Bins

Dishwasher

Laundry

Clean Toilets

Milk/Spinach/Chicken/Porridge

School-run

Bank + Playground

Dinner

Baths

Bedtime I keep my list as close as my phone, and draw a deep sense of satis- faction each time I strike a task from it. In such erasure lies joy. No matter how much I give of myself to household chores, each of the rooms under my control swiftly unravels itself again in my aftermath, as though a shadow hand were already beginning the unwritten lists of my tomorrows: more tidying, more hoovering, more dusting, more wiping and mopping and polishing. When my husband is home, we divide the chores, but when I'm alone, I work alone. I don't tell him, but I prefer it that way. I like to be in control. Despite all the chores on my list, and despite my devotion to their completion, the house looks as cheerily dishevelled as any other home of young children, no cleaner, no dirtier.

So far this morning, I have only crossed off school-run, a task which encompassed waking the children, dressing, washing, and feeding them, clearing the breakfast table, finding coats and hats and shoes, brushing teeth, shouting the word ‘shoes' several times, filling a lunchbox, checking a schoolbag, shouting for shoes again, and then, finally, walking to the school and back. Since returning home, I have still only half-filled the dishwasher, half-helped my son with his jigsaw, and half-mopped the floor – nothing worthy of deletion from my list. I cling to my list because it is this list which holds my hand through my days, breaking the hours into a series of small, achievable tasks. By the end of a good list, when I am held again in my sleeping husband's arms, this text has become a sequence of scribbles, an obliteration which I observe in joy and satisfaction, because the gradual erasure of this handwritten document makes me feel as though I have achieved some- thing of worth in my hours. The list is both my map and my compass.

Now I can feel myself starting to fall behind, so I skim the text of today's tasks to find my bearings, then set the dishwasher humming and draw a line through that word. I smile as I help the toddler find his missing jigsaw piece, clap when he completes it, and finally resort to the remote control. I don't cuddle him close as he watches The Octonauts. I don't sit on the sofa with him and close my weary eyes for ten minutes. Instead, I hurry to the kitchen, finish mopping, empty the bins, and then check those tasks off my list with a flourish.

At the sink I scrub my hands, nails, and wrists, then scrub them again. I lift sections of funnels and filters from the steam sterilizer to assemble my breastpump. These machines are not cheap and I no longer have a paying job, so I bought mine second-hand. On my screen, the ad seemed almost as poignant as the baby shoes story usually attributed to Ernest Hemingway –

Bought for €209, will sell for €45 ONO.

Used once. Every morning for months this machine and I have followed the same small ritual in order to gather milk for the babies of strangers. I unclip my bra and scoop my breast into the funnel. It's always the right breast, because my left breast is a lazy bastard: by a month post-partum it has all but given up, so both baby and machine must be fully served by the right. I press the switch, wince as it jerks my nipple awkwardly, adjust myself, and then twist the dial that controls the intensity with which the machine pulls the flesh. At first, the mechanism draws fast and firm, mimicking the baby's pattern of quick suck, until it believes that the milk must have begun to emerge. After a moment or two the pump settles into a steady cadence: long tug, release, repeat. The sensation at nipple level is like a series o...