Americas

- Publisher : Random House Trade Paperbacks; Reprint edition

- Published : 01 Feb 2022

- Pages : 416

- ISBN-10 : 1984855018

- ISBN-13 : 9781984855015

- Language : English

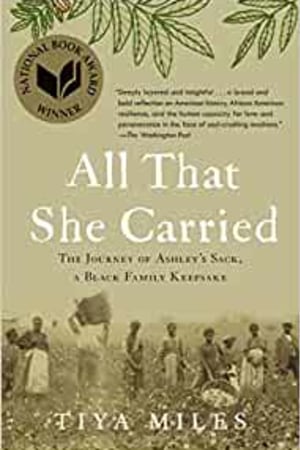

All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley's Sack, a Black Family Keepsake

NATIONAL BOOK AWARD WINNER • A renowned historian traces the life of a single object handed down through three generations of Black women to craft an extraordinary testament to people who are left out of the archives.

KIRKUS PRIZE FINALIST • FINALIST FOR THE PEN/JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH AWARD • ONE OF THE TEN BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR: The Washington Post, Slate, Vulture, Publishers Weekly • ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR: The New York Times, NPR, Time, The Boston Globe, The Atlantic, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Smithsonian Magazine, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Ms. magazine, Book Riot, Library Journal, Kirkus Reviews, Booklist

"Deeply layered and insightful . . . [a] bold reflection on American history, African American resilience, and the human capacity for love and perseverance in the face of soul-crushing madness."-The Washington Post

"A history told with brilliance and tenderness and fearlessness."-Jill Lepore, author of These Truths: A History of the United States

In 1850s South Carolina, an enslaved woman named Rose faced a crisis, the imminent sale of her daughter Ashley. Thinking quickly, she packed a cotton bag with a few precious items as a token of love and to try to ensure Ashley's survival. Soon after, the nine-year-old girl was separated from her mother and sold.

Decades later, Ashley's granddaughter Ruth embroidered this family history on the bag in spare yet haunting language-including Rose's wish that "It be filled with my Love always." Ruth's sewn words, the reason we remember Ashley's sack today, evoke a sweeping family story of loss and of love passed down through generations. Now, in this illuminating, deeply moving book inspired by Rose's gift to Ashley, historian Tiya Miles carefully unearths these women's faint presence in archival records to follow the paths of their lives-and the lives of so many women like them-to write a singular and revelatory history of the experience of slavery, and the uncertain freedom afterward, in the United States.

The search to uncover this history is part of the story itself. For where the historical record falls short of capturing Rose's, Ashley's, and Ruth's full lives, Miles turns to objects and to art as equally important sources, assembling a chorus of women's and families' stories and critiquing the scant archives that for decades have overlooked so many. The contents of Ashley's sack-a tattered dress, handfuls of pecans, a braid of hair, "my Love always"-are eloquent evidence of the lives these women lived. As she follows Ashley's journey, Miles metaphorically unpacks the bag, deepening its emotional resonance and exploring the meanings and significance of everything it contained.

All That She Carried is a poignant story of resilience and of love passed down through generations of women against steep odds. It honors the creativity and fierce resourcefulness of people who preserved family ties even when official systems refused to do so, and it serves as a visionary illustration of how to reconstruct and recount their stories today.

KIRKUS PRIZE FINALIST • FINALIST FOR THE PEN/JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH AWARD • ONE OF THE TEN BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR: The Washington Post, Slate, Vulture, Publishers Weekly • ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR: The New York Times, NPR, Time, The Boston Globe, The Atlantic, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Smithsonian Magazine, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Ms. magazine, Book Riot, Library Journal, Kirkus Reviews, Booklist

"Deeply layered and insightful . . . [a] bold reflection on American history, African American resilience, and the human capacity for love and perseverance in the face of soul-crushing madness."-The Washington Post

"A history told with brilliance and tenderness and fearlessness."-Jill Lepore, author of These Truths: A History of the United States

In 1850s South Carolina, an enslaved woman named Rose faced a crisis, the imminent sale of her daughter Ashley. Thinking quickly, she packed a cotton bag with a few precious items as a token of love and to try to ensure Ashley's survival. Soon after, the nine-year-old girl was separated from her mother and sold.

Decades later, Ashley's granddaughter Ruth embroidered this family history on the bag in spare yet haunting language-including Rose's wish that "It be filled with my Love always." Ruth's sewn words, the reason we remember Ashley's sack today, evoke a sweeping family story of loss and of love passed down through generations. Now, in this illuminating, deeply moving book inspired by Rose's gift to Ashley, historian Tiya Miles carefully unearths these women's faint presence in archival records to follow the paths of their lives-and the lives of so many women like them-to write a singular and revelatory history of the experience of slavery, and the uncertain freedom afterward, in the United States.

The search to uncover this history is part of the story itself. For where the historical record falls short of capturing Rose's, Ashley's, and Ruth's full lives, Miles turns to objects and to art as equally important sources, assembling a chorus of women's and families' stories and critiquing the scant archives that for decades have overlooked so many. The contents of Ashley's sack-a tattered dress, handfuls of pecans, a braid of hair, "my Love always"-are eloquent evidence of the lives these women lived. As she follows Ashley's journey, Miles metaphorically unpacks the bag, deepening its emotional resonance and exploring the meanings and significance of everything it contained.

All That She Carried is a poignant story of resilience and of love passed down through generations of women against steep odds. It honors the creativity and fierce resourcefulness of people who preserved family ties even when official systems refused to do so, and it serves as a visionary illustration of how to reconstruct and recount their stories today.

Editorial Reviews

"A remarkable book."-Jennifer Szalai, The New York Times

"Deeply and lovingly researched . . . a testament to the power of story, witness, and unyielding love."-Atlanta Journal-Constitution

"Through [Miles's] interpretation, the humble things in the sack take on ever-greater meaning, its very survival seems magical, and Rose's gift starts to feel momentous in scale."-Rebecca Onion, Slate

"[An] extraordinary story . . . Unique and unforgettable."-Ms.

"A brilliant exercise in historical excavation and recovery . . . With creativity, determination, and great insight, Miles illuminates the lives of women who suffered much, but never forgot the importance of love and family."-Annette Gordon-Reed, author of The Hemingses of Monticello

"[A] powerful history of women and slavery."-The New Yorker

"[A] sparkling tale."-Oprah Daily

"Tiya Miles is a gentle genius . . . All That She Carried is a gorgeous book and a model for how to read as well as feel the precious artifacts of Black women's lives."-Imani Perry, author of Breathe: A Letter to My Sons

"All That She Carried is a moving literary and visual experience about love between a mother and daughter and about many women descendants down through the years. Above all it is Miles's lyrical story, written in her signature penetrating prose, about the power of objects and memory, as well as human endurance, in the history of slavery. The book is nothing short of a revelation."-David W. Blight, Yale University, author of the Pulitzer Prize–winning Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

"Ashley's Sack, as it is known, with its short and simple message of intergenerational love, becomes a portal through which Tiya Miles views and reimagines the inner lives of Black women. She excavates the history of Black women who face insurmountable odds and invent a language that can travel across time."-Michael Eric Dyson, author of Long Time Coming: Reckoning with Race in America

"Tiya Miles uses the tools of her trade to tend to Black people, to Black mothers and daughters, to our wounds, to collective Black love and loss. This book demonstrates Miles's signature genius in its rare balance of both rigor and care."-Brittney Cooper, author of Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower

"All That She Carried is a masterpiece work of African American women's history that reveals what it takes to survive and even thrive. Read this book and then pass it on to someone you love."-Martha S. Jones, author of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted ...

"Deeply and lovingly researched . . . a testament to the power of story, witness, and unyielding love."-Atlanta Journal-Constitution

"Through [Miles's] interpretation, the humble things in the sack take on ever-greater meaning, its very survival seems magical, and Rose's gift starts to feel momentous in scale."-Rebecca Onion, Slate

"[An] extraordinary story . . . Unique and unforgettable."-Ms.

"A brilliant exercise in historical excavation and recovery . . . With creativity, determination, and great insight, Miles illuminates the lives of women who suffered much, but never forgot the importance of love and family."-Annette Gordon-Reed, author of The Hemingses of Monticello

"[A] powerful history of women and slavery."-The New Yorker

"[A] sparkling tale."-Oprah Daily

"Tiya Miles is a gentle genius . . . All That She Carried is a gorgeous book and a model for how to read as well as feel the precious artifacts of Black women's lives."-Imani Perry, author of Breathe: A Letter to My Sons

"All That She Carried is a moving literary and visual experience about love between a mother and daughter and about many women descendants down through the years. Above all it is Miles's lyrical story, written in her signature penetrating prose, about the power of objects and memory, as well as human endurance, in the history of slavery. The book is nothing short of a revelation."-David W. Blight, Yale University, author of the Pulitzer Prize–winning Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

"Ashley's Sack, as it is known, with its short and simple message of intergenerational love, becomes a portal through which Tiya Miles views and reimagines the inner lives of Black women. She excavates the history of Black women who face insurmountable odds and invent a language that can travel across time."-Michael Eric Dyson, author of Long Time Coming: Reckoning with Race in America

"Tiya Miles uses the tools of her trade to tend to Black people, to Black mothers and daughters, to our wounds, to collective Black love and loss. This book demonstrates Miles's signature genius in its rare balance of both rigor and care."-Brittney Cooper, author of Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower

"All That She Carried is a masterpiece work of African American women's history that reveals what it takes to survive and even thrive. Read this book and then pass it on to someone you love."-Martha S. Jones, author of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted ...

Readers Top Reviews

Janet Zobristdebsfea

This is an amazing g educational poignant book. No matter your race! It’s beautifully and educationally written a look into slavery in the south in the 1700-1800 hundreds

maria

A brilliant historical account of not just one Black woman’s trauma, struggle against and eventual rise above the hatred of slavery and Jim Crow…but also the stories of many, many Black families who lived through similar horrors. A celebration of family love and indomitable will to survive. Highly recommend to any mother, daughter, sister, auntie and human.

Katherine

I read Tiya Miles history of Ashley's sack immediately after reading Honore Jeffers The Love Songs of WEB Du Bois. Both are written by Black Feminist literary scholars who are immersed in their field. I feel as if I have attended a graduate seminar on slavery and Black family culture and structure. Miles traces the genealogy of four generations of women starting in the mid-nineteenth century when a mother gives her child, Ashley, a sack of belongings to help her when she is sold away during slavery. Not only does the reader follow the search for the real Ashley and her mother, but we also learn about the clothing, food, hair styles, and so much more from each of the periods covered. I would highly recommend this book.

Katherine McClugageK

Almost completely speculative regarding Ashley's sack. The research and information about the sack should have been a nice, shorter magazine article, not a book. This book is really about the plight and mistreatment of the "nonfree", not really about the history of the sack. The topic of slavery and review of the terrible daily emotional and physical tortures done to an enslaved people is admirable and important. However, this author used way too many paragraphs/chapters to say the same thing over and over. Poorly edited, and redundant to the point of boredom.

lamae

The moment I picked up this book, I took out my pen. I knew I'd mark it up. I knew I'd be taken on a journey with the author leading the way. I often do this with books I know I will love. I underline, circle and highlight. I placed this book on mud cloth covering a chest beside my bed. It is beside other books that leave me thinking and breathing again. What an exhale. Like Tiya Miles, the author, I have ancestry in Mississippi. Via this book, she took me to the south, but also to the unnameable places where black women/women period have fought for their humanity (indeed, I have seen knitting old women in the frigid North Atlantic doing something similar. Fighting!). They save themselves. They save their families. Some do so via cloth. Each stitch on fabric that may be passed on to a loved one signals their/our determination to live, but also seeable and unseeable histories involving ever-hurting people. They are still strong people. I have not finished this book. I stop to savor what it is saying. I also cannot get the hand-sewn curtains made of cotton that my late grandmother gave me out of my mind's eye. I can still see her uneven stitches. She had arthritis. She also had great love. At the time I received the curtains, which are pictured here, I was leaving for another state, but she wanted to give me something. Something that may not have been much. She gave me a part of herself when she presented those curtains. Miles, an accomplished and amazing historian, has done the same. Read this book. It will remind you of this one thing: we are strong enough to get through this difficult moment in world history. Remember the ancestors. Remember the things they have been stitched, touched, passed down. Remember.

Short Excerpt Teaser

Chapter 1

Ruth's Record

My great-grandmama told my grandmama the part she lived through that my grandmama didn't live through and my grandmama told my mama what they both lived through and my mama told me what they all lived through and we were suppose to pass it down like that from generation to generation so we'd never forget.

-Gayl Jones, Corregidora, 1975

Then I found the slave lists. There were bundles of them, in thick sheaves, each sheaf containing a stack. When a rice planter handed out shoes, he wrote down the names of who got them. To pay taxes, he made an inventory of his human property. If he bought fabric so people could make clothes, he noted how many yards were given to each person. When a woman gave birth, the date and name of the child appeared.

-Edward Ball, Slaves in the Family, 1998

As a young woman with modest means and few prospects, Ruth Middleton transformed her life by moving north. Taking a leap into the unknown as a Black woman in the 1910s required tremendous courage. Ruth was still a teenager at the time, living in Columbia, South Carolina, and laboring as a domestic. She may have already met her future fiancé, Arthur Middleton, a South Carolinian from Camden and a tiremaker by trade. And she would have known from what she heard and saw, and perhaps from incidents in her own life, that the South was still a dangerous place for African Americans at the start of the new century. The first generations to be born to freedom found few job opportunities beyond the agricultural work their forebears had done, risked indebtedness in the sharecropping system, and faced public humiliation as well as unpredictable violence in everyday life. Perhaps Ruth and Arthur evaluated their situation and determined that only drastic change would better it. For they, like so many other African Americans fed up with the dusty prejudice of the South, packed their retinue of things and traveled northward seeking safety and opportunity.

Ruth and Arthur made this move amid the uncertainty of World War I and a deadly flu epidemic, joining what historians have called the first wave of the Great Migration, which would, by the 1970s, reshape the demography and political landscape of the entire United States. African Americans who had predominantly lived in the rural South relocated in the hundreds of thousands to the urban South, urban Midwest, urban West, and urban North in search of physical security and economic opportunity. Half a million of these travelers relocated to northern cities in the period when Ruth uprooted herself, between 1914 and 1920. They pulled up stakes, packed their bags, and left behind all they knew and many whom they loved. Those who departed must have faced tough decisions about which items they could afford to bring along on the journey and which things they would give away or abandon. Practical objects like skillets and skirts, cherished things like handmade quilts, and valuable items like tools and books might each have been scrutinized, weighed, and considered. We have no inventory of a great migration of things that accompanied African Americans northward and westward. Ruth Middleton's case stands as a precious exception.

When Ruth arrived in Philadelphia around the year 1918, she brought along the cotton sack that Rose had prepared for Ashley. Ruth's attachment to the textile reflects an important aspect of women's historical experience with things. While free men have historically owned and passed down "real" property (especially in the form of land), women have typically had only "movable" property (like furniture and linens-and, if the women in question were slaveholders, people) at their disposal. Although American women possessed a limited form of property, they used that property intentionally to "assert identities, build alliances, and weave family bonds torn by marriage, death, or migration." A New England–born white woman in the colonial era, for example, cherished a passed-down painted chest not only for its function but also for the ways in which the object connected her to her women forebears, reinforcing a sense of belonging not to male ancestors but to a line of women. Ruth Middleton, who would take her husband's name upon marriage, as was the American legal custom, also took her foremother's sack as she traveled north. And one day, when she was herself on the verge of motherhood, Ruth decided to annotate it.

Ruth's fabric testament to Black love and women's perseverance did not-perhaps could not-exist in any historical archive. Though necessary to the work of uncovering the past, archives are nevertheless limited and misleading storehouses of information. While at times imposing and formal enough as to seem all-encompassing in th...

Ruth's Record

My great-grandmama told my grandmama the part she lived through that my grandmama didn't live through and my grandmama told my mama what they both lived through and my mama told me what they all lived through and we were suppose to pass it down like that from generation to generation so we'd never forget.

-Gayl Jones, Corregidora, 1975

Then I found the slave lists. There were bundles of them, in thick sheaves, each sheaf containing a stack. When a rice planter handed out shoes, he wrote down the names of who got them. To pay taxes, he made an inventory of his human property. If he bought fabric so people could make clothes, he noted how many yards were given to each person. When a woman gave birth, the date and name of the child appeared.

-Edward Ball, Slaves in the Family, 1998

As a young woman with modest means and few prospects, Ruth Middleton transformed her life by moving north. Taking a leap into the unknown as a Black woman in the 1910s required tremendous courage. Ruth was still a teenager at the time, living in Columbia, South Carolina, and laboring as a domestic. She may have already met her future fiancé, Arthur Middleton, a South Carolinian from Camden and a tiremaker by trade. And she would have known from what she heard and saw, and perhaps from incidents in her own life, that the South was still a dangerous place for African Americans at the start of the new century. The first generations to be born to freedom found few job opportunities beyond the agricultural work their forebears had done, risked indebtedness in the sharecropping system, and faced public humiliation as well as unpredictable violence in everyday life. Perhaps Ruth and Arthur evaluated their situation and determined that only drastic change would better it. For they, like so many other African Americans fed up with the dusty prejudice of the South, packed their retinue of things and traveled northward seeking safety and opportunity.

Ruth and Arthur made this move amid the uncertainty of World War I and a deadly flu epidemic, joining what historians have called the first wave of the Great Migration, which would, by the 1970s, reshape the demography and political landscape of the entire United States. African Americans who had predominantly lived in the rural South relocated in the hundreds of thousands to the urban South, urban Midwest, urban West, and urban North in search of physical security and economic opportunity. Half a million of these travelers relocated to northern cities in the period when Ruth uprooted herself, between 1914 and 1920. They pulled up stakes, packed their bags, and left behind all they knew and many whom they loved. Those who departed must have faced tough decisions about which items they could afford to bring along on the journey and which things they would give away or abandon. Practical objects like skillets and skirts, cherished things like handmade quilts, and valuable items like tools and books might each have been scrutinized, weighed, and considered. We have no inventory of a great migration of things that accompanied African Americans northward and westward. Ruth Middleton's case stands as a precious exception.

When Ruth arrived in Philadelphia around the year 1918, she brought along the cotton sack that Rose had prepared for Ashley. Ruth's attachment to the textile reflects an important aspect of women's historical experience with things. While free men have historically owned and passed down "real" property (especially in the form of land), women have typically had only "movable" property (like furniture and linens-and, if the women in question were slaveholders, people) at their disposal. Although American women possessed a limited form of property, they used that property intentionally to "assert identities, build alliances, and weave family bonds torn by marriage, death, or migration." A New England–born white woman in the colonial era, for example, cherished a passed-down painted chest not only for its function but also for the ways in which the object connected her to her women forebears, reinforcing a sense of belonging not to male ancestors but to a line of women. Ruth Middleton, who would take her husband's name upon marriage, as was the American legal custom, also took her foremother's sack as she traveled north. And one day, when she was herself on the verge of motherhood, Ruth decided to annotate it.

Ruth's fabric testament to Black love and women's perseverance did not-perhaps could not-exist in any historical archive. Though necessary to the work of uncovering the past, archives are nevertheless limited and misleading storehouses of information. While at times imposing and formal enough as to seem all-encompassing in th...