Social Sciences

- Publisher : One World

- Published : 12 Apr 2022

- Pages : 272

- ISBN-10 : 1984820419

- ISBN-13 : 9781984820419

- Language : English

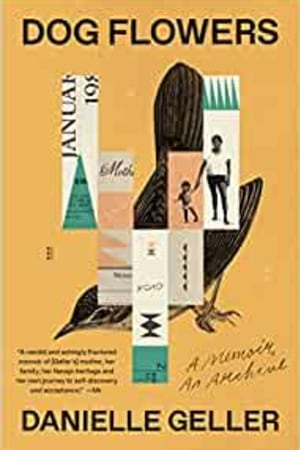

Dog Flowers: A Memoir, an Archive

A daughter returns home to the Navajo reservation to retrace her mother's life in a memoir that is both a narrative and an archive of one family's troubled history.

"A candid and achingly fractured memoir of [Geller's] mother, her family, her Navajo heritage and her own journey to self-discovery and acceptance."-Ms.

ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR: Esquire, She Reads

When Danielle Geller's mother dies of alcohol withdrawal during an attempt to get sober, Geller returns to Florida and finds her mother's life packed into eight suitcases. Most were filled with clothes, except for the last one, which contained diaries, photos, and letters, a few undeveloped disposable cameras, dried sage, jewelry, and the bandana her mother wore on days she skipped a hair wash.

Geller, an archivist and a writer, uses these pieces of her mother's life to try and understand her mother's relationship to home, and their shared need to leave it. Geller embarks on a journey where she confronts her family's history and the decisions that she herself had been forced to make while growing up, a journey that will end at her mother's home: the Navajo reservation.

Dog Flowers is an arresting, photo-lingual memoir that masterfully weaves together images and text to examine mothers and mothering, sisters and caretaking, and colonized bodies. Exploring loss and inheritance, beauty and balance, Danielle Geller pays homage to our pasts, traditions, and heritage, to the families we are given and the families we choose.

"A candid and achingly fractured memoir of [Geller's] mother, her family, her Navajo heritage and her own journey to self-discovery and acceptance."-Ms.

ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR: Esquire, She Reads

When Danielle Geller's mother dies of alcohol withdrawal during an attempt to get sober, Geller returns to Florida and finds her mother's life packed into eight suitcases. Most were filled with clothes, except for the last one, which contained diaries, photos, and letters, a few undeveloped disposable cameras, dried sage, jewelry, and the bandana her mother wore on days she skipped a hair wash.

Geller, an archivist and a writer, uses these pieces of her mother's life to try and understand her mother's relationship to home, and their shared need to leave it. Geller embarks on a journey where she confronts her family's history and the decisions that she herself had been forced to make while growing up, a journey that will end at her mother's home: the Navajo reservation.

Dog Flowers is an arresting, photo-lingual memoir that masterfully weaves together images and text to examine mothers and mothering, sisters and caretaking, and colonized bodies. Exploring loss and inheritance, beauty and balance, Danielle Geller pays homage to our pasts, traditions, and heritage, to the families we are given and the families we choose.

Editorial Reviews

"[A] transcendent story [of] the agonizing cycles of abuse and addiction . . . with deep compassion about the limitations of the people we love."-Esquire

"This shattering memoir . . . combines image and text to reveal a portrait of home."-Elle

"Dog Flowers by Danielle Geller is a journey story we've never read before. Geller travels through snippets of her own life and that of her mother's, creating a narrative where all roads lead to her mother's home in the Navajo Nation. It's an honest, intimate, and heart-wrenching memoir that explores fractured family, the damaging effects of alcoholism and poverty, and what it means to seek healing from legacies of trauma. This book gave me chills. Trained as a librarian and archivist, Geller has created a type of archive, a living collection of memories and documents that speak to a life that is at once precisely individualistic while also being universally resonant. Read this book."-Kali Fajardo-Anstine, author ofSabrina & Corina

"Dog Flowers pulls the few remaining threads of an unraveled family life. This courageous, honest, desperate, tender, and compelling book tells a daughter's story of her troubled mother. In Dog Flowers, we learn that a handful of threads can never reweave the blanket of family, or patch up what a mother's abandonment has torn . . . Even [Geller's] return to her mother's Navajo Nation does not bring about an easy cultural reunion, although it does give us a satisfying sense that while an immediate family can fall apart, an extended family, a tribe, ties a tight web that might just hold."-Heid E. Erdrich, award-winning poet, author, and editor of the award-winning New Poets of Native Nations

"Combining images and text, Dog Flowers tells Geller's personal story. She writes of the loss of her mother to alcohol withdrawal and the journey she took to learn more about her mother's life. The search takes her to a Navajo reservation, her mother's onetime home, where an uneasy reunion and revelations-equal parts hopeful and heartbreaking-await. A beautiful book by a Native American author, Dog Flowers

"This shattering memoir . . . combines image and text to reveal a portrait of home."-Elle

"Dog Flowers by Danielle Geller is a journey story we've never read before. Geller travels through snippets of her own life and that of her mother's, creating a narrative where all roads lead to her mother's home in the Navajo Nation. It's an honest, intimate, and heart-wrenching memoir that explores fractured family, the damaging effects of alcoholism and poverty, and what it means to seek healing from legacies of trauma. This book gave me chills. Trained as a librarian and archivist, Geller has created a type of archive, a living collection of memories and documents that speak to a life that is at once precisely individualistic while also being universally resonant. Read this book."-Kali Fajardo-Anstine, author ofSabrina & Corina

"Dog Flowers pulls the few remaining threads of an unraveled family life. This courageous, honest, desperate, tender, and compelling book tells a daughter's story of her troubled mother. In Dog Flowers, we learn that a handful of threads can never reweave the blanket of family, or patch up what a mother's abandonment has torn . . . Even [Geller's] return to her mother's Navajo Nation does not bring about an easy cultural reunion, although it does give us a satisfying sense that while an immediate family can fall apart, an extended family, a tribe, ties a tight web that might just hold."-Heid E. Erdrich, award-winning poet, author, and editor of the award-winning New Poets of Native Nations

"Combining images and text, Dog Flowers tells Geller's personal story. She writes of the loss of her mother to alcohol withdrawal and the journey she took to learn more about her mother's life. The search takes her to a Navajo reservation, her mother's onetime home, where an uneasy reunion and revelations-equal parts hopeful and heartbreaking-await. A beautiful book by a Native American author, Dog Flowers

Readers Top Reviews

Td3Kitties & Kind

Danielle Gellar’s memoir was a bit different from what I was expecting, but I found I was very much invested in how she moved on with her life after growing up in such a dysfunctional family. It’s sad to think that such an unstable family situation is what some children know as normal and this was the case with Gellar’s family. Alcoholism and brief stints in jail become somewhat of a regular occurrence. Raised mainly by their paternal grandmother, Danielle and her sister manage to keep a connection with their parents, even though they see them sporadically. Danielle’s mother was raised on a Navajo reservation, but left as a young woman and seemingly abandoned her heritage, having little contact with her family remaining on the reservation. As a result, Danielle and her sister are only able to fill in the blanks after their mother has passed away. There wasn’t as much information about the Navajo traditions and life on the reservation as I was hoping for. It seems as if Gellar may have been a bit overwhelmed and unable to absorb it all in the few visits she made. Also, there were some situations on the reservation she wisely began to avoid. I did like the fact that she learned to weave, so it was good to see her embrace that part of her heritage. Trigger warnings for those readers sensitive to drug and alcohol abuse. Many thanks to NetGalley and Random House Publishing Group for allowing me to read an advance copy and give my honest review.

Ashley HubbardAsh

I’d like to thank One World/Random House and Netgalley for so generously providing me a copy of Dog Flowers. All opinions are, of course, my own. "I was angry at things outside our control. I was angry at the broken communities we were born into, and the godly men who perpetuated the cycles of abuse. Who told us to seek happiness in ignorance and faith in a God who seemed indifferent to our suffering. Who taught us to forgive too readily, and that forgiveness restored power, when in my experience, forgiveness had only taken my power away." In Dog Flowers, Danielle Geller rips your heart out. She presents her own life in this heart-wrenching memoir that partly revisits her childhood and young adulthood and partly her mother’s life. Geller recalls all the moments that shaped her and they’re not necessarily pretty. Everything from abuse, neglect, abandonment, hopelessness, mental illness, and loneliness. The memoir begins in real-life after her mother’s death and in the book it begins when Danielle receives a phone call that her mother, Lauren “Tweety” Lee is in the hospital, dying. She makes the decision to go despite the hell she went through. Her mother was never a real presence in her life. Her and her sister, Eileen, were shuffled from their alcoholic and abusive father and their grandmother (father’s mother). After visiting her mother in the hospital, Danielle returns to Boston with a suitcase full of letters, receipts, diaries, and photos from her mother’s relatively short life. This memoir is heavy, raw, and doesn’t hold anything back. Not only does it bring to light very important issues that many face whether it be abandonment, abuse, alcoholism, addiction, and more, but it also gives a real snippet into the life of Navajo culture and what it’s like to be born into a life where the cards are stacked against you. The style of writing was a bit unusual for me, but I soon came to love it. Danielle can abruptly change scenes, but somehow it works.

SvennAshley Hubba

I enjoyed this memoir. The author has a nice writing style and I appreciated the details of Navajo culture as she experienced her family.

Liz ShannonSvennA

A story that is simultaneously tragic and beautiful. Danielle Geller does a brilliant job of telling a difficult story, incorporating archival materials to give the reader a real sense of the real-life characters.

D. H. Greyerbiehl

This is a gritty outpouring of a Navaho woman’s real experiences growing up in a dysfunctional household. It details stories of alcoholism and violence by her parents and other relationships and it’s effect on her struggling to find safety and love.

Short Excerpt Teaser

and boy it burns me up

My mother left the Navajo reservation almost as soon as she could. At nineteen, she moved to the city, as many do, to continue her education. In a brown and water-stained copy of an incomplete job application, I found evidence of these early years: From April 4, 1983, until July 1, 1984, she took classes on cultural awareness, health education, and leadership at the "Albuquerque Job Corps Center." ("It was the best," a woman who attended the school in the late eighties wrote in a recent Google review. "I will always remember the good times I had.") For work experience, my mother found part-time jobs in retail at Kirtland Air Force Base; as a file clerk at the "Albuquerque Rehab. Med. Center"; and as a typist at the "New Mexico State Labor Com.," a position she held for only a month.

In August, my mother moved to Prescott, Arizona, and began working as a waitress at the "Palace Hotel Restaurant," where my parents met. My father told me they met at the Hotel St. Michael, which was not true, but my father always loved the sound of his own name.

My father worked for his brother's computer company as a traveling technician. Those were his glittering days: He charged expensive rental cars to disposable credit cards and drove back and forth across the country. He gave the keys to his cars and hotel rooms to the homeless and traveling people he met. He dropped acid in the desert and once, he claimed, met a man entirely surrounded by a golden aura-Jesus Christ himself.

The way my father told their story, I always believed my parents fell in love quickly. That after those early smoke-filled nights, she left with him when he returned to Florida, where I was born in the summer of 1986. But the application I found was dated March 27, 1985, a few months after she quit her job in Prescott and moved back to New Mexico. The reason given: "Looking for Another type of job."

When I asked my father how my mother got to Florida, he said she called him months after they first met. "I could come see you," she said.

When I called Eileen to tell her our mother was dying, I wasn't sure what words to use. I repeated the doctor's words: Sick. Heart attack. Nonresponsive. Very, very sick.

She asked, from a distance, what I meant.

Eileen and I were not good sisters to each other. We never held each other, and we didn't end conversations with love. But in that moment, I would have given anything to take her in my arms, to give her some small comfort. "Her heart doesn't work anymore," I told her. "She's not going to get better."

"What?" My sister's voice edged on anger, an anger I had always feared.

"She's dying," I said, simply, and then listened as her anger dropped into heavy, wracking sobs. I couldn't take my words back, and I couldn't think of anything else to say. All I could do was listen to her cry until she finally decided to hang up.

She called me a few hours later. Her voice sounded like smoke rising, faint and curling. She was high. She asked if I planned to go down to Florida.

I had been sitting in front of my computer with flights mapped out, but I hadn't been able to convince myself to buy a ticket. I wasn't sure I wanted to go.

"Someone has to be with her," Eileen said. She was somewhere in Montana, and she said she would try to buy a bus ticket, but she worried she wouldn't make it to Florida in time.

The walls of my room were painted cornflower blue.

"I'll go," I promised.

"You can't go down there alone," she said, but we both knew I would. "I'm sorry, Danielle," she added, beginning to cry again. "I'm sorry."

A few months after my mother moved to South Florida, she was pregnant with me. My father claimed she could get pregnant off a toilet seat. My father's mother convinced her to keep the baby, and she offered them a two-bedroom apartment in a building she owned on Nokomis Avenue, a chalk-white dirt road.

Our neighbors were inconstant. My grandmother's tenants were as poor as our neighborhood, and no one seemed to stay for long. She liked to tell the story of one of her tenants who dragged all his furniture, even the refrigerator, onto the lawn in the middle of the day. She couldn't get a reason out of him-he talked nonsense, raving about who knew what, so she called an ambulance. Later she found out his rotting teeth were the cause of his madness, but she found the story funny and laughed each time she told it.

I was too young to remember most of our time in that apartment, but in my mother's things I find ...

My mother left the Navajo reservation almost as soon as she could. At nineteen, she moved to the city, as many do, to continue her education. In a brown and water-stained copy of an incomplete job application, I found evidence of these early years: From April 4, 1983, until July 1, 1984, she took classes on cultural awareness, health education, and leadership at the "Albuquerque Job Corps Center." ("It was the best," a woman who attended the school in the late eighties wrote in a recent Google review. "I will always remember the good times I had.") For work experience, my mother found part-time jobs in retail at Kirtland Air Force Base; as a file clerk at the "Albuquerque Rehab. Med. Center"; and as a typist at the "New Mexico State Labor Com.," a position she held for only a month.

In August, my mother moved to Prescott, Arizona, and began working as a waitress at the "Palace Hotel Restaurant," where my parents met. My father told me they met at the Hotel St. Michael, which was not true, but my father always loved the sound of his own name.

My father worked for his brother's computer company as a traveling technician. Those were his glittering days: He charged expensive rental cars to disposable credit cards and drove back and forth across the country. He gave the keys to his cars and hotel rooms to the homeless and traveling people he met. He dropped acid in the desert and once, he claimed, met a man entirely surrounded by a golden aura-Jesus Christ himself.

The way my father told their story, I always believed my parents fell in love quickly. That after those early smoke-filled nights, she left with him when he returned to Florida, where I was born in the summer of 1986. But the application I found was dated March 27, 1985, a few months after she quit her job in Prescott and moved back to New Mexico. The reason given: "Looking for Another type of job."

When I asked my father how my mother got to Florida, he said she called him months after they first met. "I could come see you," she said.

When I called Eileen to tell her our mother was dying, I wasn't sure what words to use. I repeated the doctor's words: Sick. Heart attack. Nonresponsive. Very, very sick.

She asked, from a distance, what I meant.

Eileen and I were not good sisters to each other. We never held each other, and we didn't end conversations with love. But in that moment, I would have given anything to take her in my arms, to give her some small comfort. "Her heart doesn't work anymore," I told her. "She's not going to get better."

"What?" My sister's voice edged on anger, an anger I had always feared.

"She's dying," I said, simply, and then listened as her anger dropped into heavy, wracking sobs. I couldn't take my words back, and I couldn't think of anything else to say. All I could do was listen to her cry until she finally decided to hang up.

She called me a few hours later. Her voice sounded like smoke rising, faint and curling. She was high. She asked if I planned to go down to Florida.

I had been sitting in front of my computer with flights mapped out, but I hadn't been able to convince myself to buy a ticket. I wasn't sure I wanted to go.

"Someone has to be with her," Eileen said. She was somewhere in Montana, and she said she would try to buy a bus ticket, but she worried she wouldn't make it to Florida in time.

The walls of my room were painted cornflower blue.

"I'll go," I promised.

"You can't go down there alone," she said, but we both knew I would. "I'm sorry, Danielle," she added, beginning to cry again. "I'm sorry."

A few months after my mother moved to South Florida, she was pregnant with me. My father claimed she could get pregnant off a toilet seat. My father's mother convinced her to keep the baby, and she offered them a two-bedroom apartment in a building she owned on Nokomis Avenue, a chalk-white dirt road.

Our neighbors were inconstant. My grandmother's tenants were as poor as our neighborhood, and no one seemed to stay for long. She liked to tell the story of one of her tenants who dragged all his furniture, even the refrigerator, onto the lawn in the middle of the day. She couldn't get a reason out of him-he talked nonsense, raving about who knew what, so she called an ambulance. Later she found out his rotting teeth were the cause of his madness, but she found the story funny and laughed each time she told it.

I was too young to remember most of our time in that apartment, but in my mother's things I find ...