Genre Fiction

- Publisher : Vintage

- Published : 14 Mar 2006

- Pages : 288

- ISBN-10 : 1400078776

- ISBN-13 : 9781400078776

- Language : English

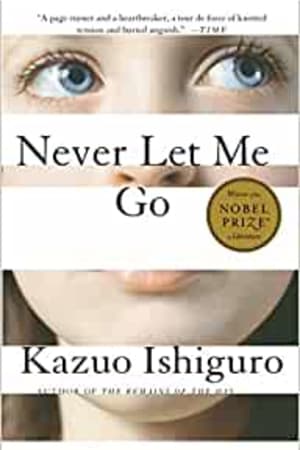

Never Let Me Go

From the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature and author of the Booker Prize–winning novel The Remains of the Day comes a devastating novel of innocence, knowledge, and loss.

As children, Kathy, Ruth, and Tommy were students at Hailsham, an exclusive boarding school secluded in the English countryside. It was a place of mercurial cliques and mysterious rules where teachers were constantly reminding their charges of how special they were. Now, years later, Kathy is a young woman. Ruth and Tommy have reentered her life. And for the first time she is beginning to look back at their shared past and understand just what it is that makes them special-and how that gift will shape the rest of their time together. Suspenseful, moving, beautifully atmospheric, Never Let Me Go is modern classic.

As children, Kathy, Ruth, and Tommy were students at Hailsham, an exclusive boarding school secluded in the English countryside. It was a place of mercurial cliques and mysterious rules where teachers were constantly reminding their charges of how special they were. Now, years later, Kathy is a young woman. Ruth and Tommy have reentered her life. And for the first time she is beginning to look back at their shared past and understand just what it is that makes them special-and how that gift will shape the rest of their time together. Suspenseful, moving, beautifully atmospheric, Never Let Me Go is modern classic.

Editorial Reviews

"A page turner and a heartbreaker, a tour de force of knotted tension and buried anguish." -Time

"A Gothic tour de force. . . . A tight, deftly controlled story . . . . Just as accomplished [as The Remains of the Day] and, in a very different way, just as melancholy and alarming." -The New York Times

"Elegaic, deceptively lovely. . . . As always, Ishiguro pulls you under." -Newsweek

"Superbly unsettling, impeccably controlled . . . . The book's irresistible power comes from Ishiguro's matchless ability to expose its dark heart in careful increments." -Entertainment Weekly

"A Gothic tour de force. . . . A tight, deftly controlled story . . . . Just as accomplished [as The Remains of the Day] and, in a very different way, just as melancholy and alarming." -The New York Times

"Elegaic, deceptively lovely. . . . As always, Ishiguro pulls you under." -Newsweek

"Superbly unsettling, impeccably controlled . . . . The book's irresistible power comes from Ishiguro's matchless ability to expose its dark heart in careful increments." -Entertainment Weekly

Readers Top Reviews

Anne

This is an amazing book. Beautifully written and the mundane style and content of the story makes it equally engrossing, touching and horrifying. It had quite a profound effect on me, it very cleverly explores the way exploitation happens to certain sectors of society, and how people can justify evil behaviour in the name of the greater good, and additionally how people who are treated appallingly just accept their lot.

Michael X SmithWebe

Never Let Me Go is set in an alternative reality late 1990s England where some people are cloned to be organ donors. They are brought up in special schools in ignorance of the larger society in which their fate is decided. What that society is like and how the donors are bred we are never told. The author’s intention seems to be to explore the human condition through an intensified version of it. However, there are problems. Donors have only initials for their surnames, to signify their socially incomplete status and their partial anonymity as containers of spare body parts. Like all donors, the narrator, Kathy H, has limited knowledge. This is appropriate to her situation but frustrating for the reader, who wants to know more about this alternative reality, particularly how could the donor caste be so passive, so accepting of their fate? Even in the most extreme of human circumstances—the Holocaust, for example, or Stalin’s Gulag—there was resistance. Humans simply aren’t made to be passive receptors of a ghastly fate designated by others. Such a situation can be presented convincingly, as in Huxley’s Brave New World, but that novel presents a near-complete system of control, where members of the rigidly class-stratified society are designed in laboratories, are chemically produced, so that an epsilon is content to operate a lift all day. In Never, no explanation is given and the partial picture presented through the limited viewpoint of the narrator leaves too many questions unanswered. Explanations conveniently but awkwardly inserted in an unlikely character monologue cum question-and-answer session towards the end of the novel are inadequate and testify to the author’s awareness of the need for explanation rather than satisfy that need. There is also a problem with the narrative voice. Reading such a limited narrator’s account for almost 300 pages becomes tedious, like listening to the conversation of schoolchildren for hours. The deliberately flat prose style and the endlessly detailed trivia frustrate the reader’s desire for a more engaging narrative voice. Some gain in power towards the end of the novel is not enough to offset the slog of getting there. It may be objected that the position of the donors is simply an emphatic version of mortality and that therefore they represent all of us, but the problem of the limiting narrative voice and sketchy characterisation remains. Never’s alternative or exaggerated reality doesn’t tell us anything we don’t already know about our ultimate fate, and our own thoughts about it may be more interesting than the flat monologue of Kathy H. Ishiguro’s novel is a sincere attempt to explore what it means to be human: our relationships with others, our need for love and achievement, and the inevitability of death, but the device of an incompletely imagined alternative reality nar...

Marcus

The first person narrator, Kathy, draws you gently into her soap opera of insults imagined and slights half-intended, set initially in a private boarding school. Never exciting, but always fascinating, the narrative keeps us turning the pages by its very banality, and its believableness. As the story unfolds, we realise that things are not as straightforward as the blandness of the narrative implies. Is this science fiction? Yet the horror is always tempered by the fatalism and acceptance of the narrator and her schoolmates. Why does this far-fetched story ring so true? As gently as Kathy's narrative, it dawns on us that this is not science fiction, but a description of our own lives. The stoic acceptance the participants have for their truncated, pointless lives mirrors our own acceptance of our mortality, and the ultimate pointlessness of our own existence. This book works because of the form of its narrative -- the soap-opera banality and fine-grained observation. In the detail, Ishiguro finds the soul of his characters, and us his readers.

T SchoenDaphne

I would probably rate this 3.5 stars if that was an option. I found myself pretty detached while reading this...not in my usually hurry to finish and see how the characters and story developed. Perhaps that was part of the author’s effort? I’m not sure. Our narrator, Kathy, was detached as well. Detached from her own experiences and even somewhat detached from the losses she experiences. Only Tommy, who would sometimes give into rages, seemed to FEEL the appropriate outrage at times. But then it would get tucked back inside and hidden. Tommy’s art is what I found most interesting and distinctive. The fact that he quit trying for awhile because his art was ‘no good’ but then later, while his art was still different... it became so stylized and small...maybe mechanical, but precise. I think Tommy’s art and the precision of it shows that each of these people is precise. So many little parts make us into who we are... In the end, I found this book sad. It’s another testament of man’s inhumanity towards man. If we can make ourselves believe someone is ‘less than’ we are, in any way, then we can justify our mistreatment. The fact that we do it ‘in the name of science’ doesn’t work for me. I guess I believe in the soul. I believe in the sanctity of people... of life.

Short Excerpt Teaser

My name is Kathy H. I'm thirty-one years old, and I've been a carer now for over eleven years. That sounds long enough, I know, but actually they want me to go on for another eight months, until the end of this year. That'll make it almost exactly twelve years. Now I know my being a carer so long isn't necessarily because they think I'm fantastic at what I do. There are some really good carers who've been told to stop after just two or three years. And I can think of one carer at least who went on for all of fourteen years despite being a complete waste of space. So I'm not trying to boast. But then I do know for a fact they've been pleased with my work, and by and large, I have too. My donors have always tended to do much better than expected. Their recovery times have been impressive, and hardly any of them have been classified as "agitated," even before fourth donation. Okay, maybe I am boasting now. But it means a lot to me, being able to do my work well, especially that bit about my donors staying "calm." I've developed a kind of instinct around donors. I know when to hang around and comfort them, when to leave them to themselves; when to listen to everything they have to say, and when just to shrug and tell them to snap out of it.

Anyway, I'm not making any big claims for myself. I know carers, working now, who are just as good and don't get half the credit. If you're one of them, I can understand how you might get resentful-about my bedsit, my car, above all, the way I get to pick and choose who I look after. And I'm a Hailsham student-which is enough by itself sometimes to get people's backs up. Kathy H., they say, she gets to pick and choose, and she always chooses her own kind: people from Hailsham, or one of the other privileged estates. No wonder she has a great record. I've heard it said enough, so I'm sure you've heard it plenty more, and maybe there's something in it. But I'm not the first to be allowed to pick and choose, and I doubt if I'll be the last. And anyway, I've done my share of looking after donors brought up in every kind of place. By the time I finish, remember, I'll have done twelve years of this, and it's only for the last six they've let me choose.

And why shouldn't they? Carers aren't machines. You try and do your best for every donor, but in the end, it wears you down. You don't have unlimited patience and energy. So when you get a chance to choose, of course, you choose your own kind. That's natural. There's no way I could have gone on for as long as I have if I'd stopped feeling for my donors every step of the way. And anyway, if I'd never started choosing, how would I ever have got close again to Ruth and Tommy after all those years?

But these days, of course, there are fewer and fewer donors left who I remember, and so in practice, I haven't been choosing that much. As I say, the work gets a lot harder when you don't have that deeper link with the donor, and though I'll miss being a carer, it feels just about right to be finishing at last come the end of the year.

Ruth, incidentally, was only the third or fourth donor I got to choose. She already had a carer assigned to her at the time, and I remember it taking a bit of nerve on my part. But in the end I managed it, and the instant I saw her again, at that recovery centre in Dover, all our differences-while they didn't exactly vanish-seemed not nearly as important as all the other things: like the fact that we'd grown up together at Hailsham, the fact that we knew and remembered things no one else did. It's ever since then, I suppose, I started seeking out for my donors people from the past, and whenever I could, people from Hailsham.

There have been times over the years when I've tried to leave Hailsham behind, when I've told myself I shouldn't look back so much. But then there came a point when I just stopped resisting. It had to do with this particular donor I had once, in my third year as a carer; it was his reaction when I mentioned I was from Hailsham. He'd just come through his third donation, it hadn't gone well, and he must have known he wasn't going to make it. He could hardly breathe, but he looked towards me and said: "Hailsham. I bet that was a beautiful place." Then the next morning, when I was making conversation to keep his mind off it all, and I asked where he'd grown up, he mentioned some place in Dorset and his face beneath the blotches went into a completely new kind of grimace. And I realised then how desperately he didn't want reminded. Instead, he wanted to hear about Hailsham.

So over the next five or six days, I told him whatever he wanted to know, and he'd lie there, all hooked up, a gentle smile breaking through. He'd ask me about the big things and the little things. About our guardians, about how w...

Anyway, I'm not making any big claims for myself. I know carers, working now, who are just as good and don't get half the credit. If you're one of them, I can understand how you might get resentful-about my bedsit, my car, above all, the way I get to pick and choose who I look after. And I'm a Hailsham student-which is enough by itself sometimes to get people's backs up. Kathy H., they say, she gets to pick and choose, and she always chooses her own kind: people from Hailsham, or one of the other privileged estates. No wonder she has a great record. I've heard it said enough, so I'm sure you've heard it plenty more, and maybe there's something in it. But I'm not the first to be allowed to pick and choose, and I doubt if I'll be the last. And anyway, I've done my share of looking after donors brought up in every kind of place. By the time I finish, remember, I'll have done twelve years of this, and it's only for the last six they've let me choose.

And why shouldn't they? Carers aren't machines. You try and do your best for every donor, but in the end, it wears you down. You don't have unlimited patience and energy. So when you get a chance to choose, of course, you choose your own kind. That's natural. There's no way I could have gone on for as long as I have if I'd stopped feeling for my donors every step of the way. And anyway, if I'd never started choosing, how would I ever have got close again to Ruth and Tommy after all those years?

But these days, of course, there are fewer and fewer donors left who I remember, and so in practice, I haven't been choosing that much. As I say, the work gets a lot harder when you don't have that deeper link with the donor, and though I'll miss being a carer, it feels just about right to be finishing at last come the end of the year.

Ruth, incidentally, was only the third or fourth donor I got to choose. She already had a carer assigned to her at the time, and I remember it taking a bit of nerve on my part. But in the end I managed it, and the instant I saw her again, at that recovery centre in Dover, all our differences-while they didn't exactly vanish-seemed not nearly as important as all the other things: like the fact that we'd grown up together at Hailsham, the fact that we knew and remembered things no one else did. It's ever since then, I suppose, I started seeking out for my donors people from the past, and whenever I could, people from Hailsham.

There have been times over the years when I've tried to leave Hailsham behind, when I've told myself I shouldn't look back so much. But then there came a point when I just stopped resisting. It had to do with this particular donor I had once, in my third year as a carer; it was his reaction when I mentioned I was from Hailsham. He'd just come through his third donation, it hadn't gone well, and he must have known he wasn't going to make it. He could hardly breathe, but he looked towards me and said: "Hailsham. I bet that was a beautiful place." Then the next morning, when I was making conversation to keep his mind off it all, and I asked where he'd grown up, he mentioned some place in Dorset and his face beneath the blotches went into a completely new kind of grimace. And I realised then how desperately he didn't want reminded. Instead, he wanted to hear about Hailsham.

So over the next five or six days, I told him whatever he wanted to know, and he'd lie there, all hooked up, a gentle smile breaking through. He'd ask me about the big things and the little things. About our guardians, about how w...