Social Sciences

- Publisher : Crown; 1ST edition

- Published : 17 Oct 2006

- Pages : 375

- ISBN-10 : 0307237699

- ISBN-13 : 9780307237699

- Language : English

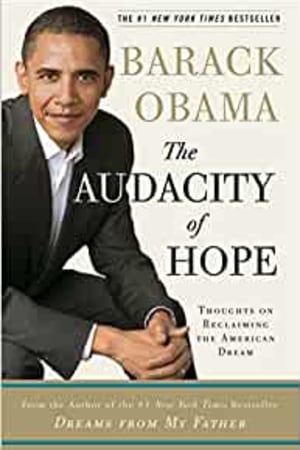

The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream

#1 NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • Barack Obama's lucid vision of America's place in the world and call for a new kind of politics that builds upon our shared understandings as Americans, based on his years in the Senate

"In our lowdown, dispiriting era, Obama's talent for proposing humane, sensible solutions with uplifting, elegant prose does fill one with hope."-Michael Kazin, The Washington Post

In July 2004, four years before his presidency, Barack Obama electrified the Democratic National Convention with an address that spoke to Americans across the political spectrum. One phrase in particular anchored itself in listeners' minds, a reminder that for all the discord and struggle to be found in our history as a nation, we have always been guided by a dogged optimism in the future, or what Obama called "the audacity of hope."

The Audacity of Hope is Barack Obama's call for a different brand of politics-a politics for those weary of bitter partisanship and alienated by the "endless clash of armies" we see in congress and on the campaign trail; a politics rooted in the faith, inclusiveness, and nobility of spirit at the heart of "our improbable experiment in democracy." He explores those forces-from the fear of losing to the perpetual need to raise money to the power of the media-that can stifle even the best-intentioned politician. He also writes, with surprising intimacy and self-deprecating humor, about settling in as a senator, seeking to balance the demands of public service and family life, and his own deepening religious commitment.

At the heart of this book is Barack Obama's vision of how we can move beyond our divisions to tackle concrete problems. He examines the growing economic insecurity of American families, the racial and religious tensions within the body politic, and the transnational threats-from terrorism to pandemic-that gather beyond our shores. And he grapples with the role that faith plays in a democracy-where it is vital and where it must never intrude. Underlying his stories is a vigorous search for connection: the foundation for a radically hopeful political consensus.

Only by returning to the principles that gave birth to our Constitution, Obama says, can Americans repair a political process that is broken, and restore to working order a government that has fallen dangerously out of touch with millions of ordinary Americans. Those Americans are out there, he writes-"waiting for Republicans and Democrats to catch up with them."

"In our lowdown, dispiriting era, Obama's talent for proposing humane, sensible solutions with uplifting, elegant prose does fill one with hope."-Michael Kazin, The Washington Post

In July 2004, four years before his presidency, Barack Obama electrified the Democratic National Convention with an address that spoke to Americans across the political spectrum. One phrase in particular anchored itself in listeners' minds, a reminder that for all the discord and struggle to be found in our history as a nation, we have always been guided by a dogged optimism in the future, or what Obama called "the audacity of hope."

The Audacity of Hope is Barack Obama's call for a different brand of politics-a politics for those weary of bitter partisanship and alienated by the "endless clash of armies" we see in congress and on the campaign trail; a politics rooted in the faith, inclusiveness, and nobility of spirit at the heart of "our improbable experiment in democracy." He explores those forces-from the fear of losing to the perpetual need to raise money to the power of the media-that can stifle even the best-intentioned politician. He also writes, with surprising intimacy and self-deprecating humor, about settling in as a senator, seeking to balance the demands of public service and family life, and his own deepening religious commitment.

At the heart of this book is Barack Obama's vision of how we can move beyond our divisions to tackle concrete problems. He examines the growing economic insecurity of American families, the racial and religious tensions within the body politic, and the transnational threats-from terrorism to pandemic-that gather beyond our shores. And he grapples with the role that faith plays in a democracy-where it is vital and where it must never intrude. Underlying his stories is a vigorous search for connection: the foundation for a radically hopeful political consensus.

Only by returning to the principles that gave birth to our Constitution, Obama says, can Americans repair a political process that is broken, and restore to working order a government that has fallen dangerously out of touch with millions of ordinary Americans. Those Americans are out there, he writes-"waiting for Republicans and Democrats to catch up with them."

Editorial Reviews

PrologueIt's been almost ten years since I first ran for political office. I was thirty-five at the time, four years out of law school, recently married, and generally impatient with life. A seat in the Illinois legislature had opened up, and several friends suggested that I run, thinking that my work as a civil rights lawyer, and contacts from my days as a community organizer, would make me a viable candidate. After discussing it with my wife, I entered the race and proceeded to do what every first-time candidate does: I talked to anyone who would listen. I went to block club meetings and church socials, beauty shops and barbershops. If two guys were standing on a corner, I would cross the street to hand them campaign literature. And everywhere I went, I'd get some version of the same two questions."Where'd you get that funny name?"And then: "You seem like a nice enough guy. Why do you want to go into something dirty and nasty like politics?"I was familiar with the question, a variant on the questions asked of me years earlier, when I'd first arrived in Chicago to work in low-income neighborhoods. It signaled a cynicism not simply with politics but with the very notion of a public life, a cynicism that–at least in the South Side neighborhoods I sought to represent–had been nourished by a generation of broken promises. In response, I would usually smile and nod and say that I understood the skepticism, but that there was–and always had been–another tradition to politics, a tradition that stretched from the days of the country's founding to the glory of the civil rights movement, a tradition based on the simple idea that we have a stake in one another, and that what binds us together is greater than what drives us apart, and that if enough people believe in the truth of that proposition and act on it, then we might not solve every problem, but we can get something meaningful done. It was a pretty convincing speech, I thought. And although I'm not sure that the people who heard me deliver it were similarly impressed, enough of them appreciated my earnestness and youthful swagger that I made it to the Illinois legislature.Six years later, when I decided to run for the United States Senate, I wasn't so sure of myself.By all appearances, my choice of careers seemed to have worked out. After spending my two terms during which I labored in the minority, Democrats had gained control of the state senate, and I had subsequently passed a slew of bills, from reforms of the Illinois death penalty system to an expansion of the state's health program for kids. I had continued to teach at the University of Chicago Law School, a job I enjoyed, and was frequently invited to speak around town. I had preserved my independence, my good name, and my marriage, all of which, statistically speaking, had been pla...

Readers Top Reviews

Kwame WireduRober

One of the few books that’s made a lasting impact on my personal and professional life. A must read for any young person wanting to serve his/her nation with wit, goodwill and the leadership our generation deserves. I️ am grateful to the author!

Lavonna L. Downin

Once more, I am impressed with the insights into the man and his decisions during his presidency. This writing confirms the soul of a philosopher.

coming soonLavonn

Obama takes you through his early years to is early days as a Junior Illinois Senator. I was surprised to learn of Obama’s more moderate views on capitalism and defense. I also appreciated his honesty about his loss on his first campaign and challenges he faced being a husband and father. This book gives you a glimpse of what Obama felt was important and ultimately lead to his Presidential agenda.

Kindle coming so

Barack Obama our first African American President of the United States tells his story of his life before becoming our President by telling about his family, true values, common goals and differences, and compromises. A must read.

k pollockStanwick

Should be called "The Audacity of Thinking I'm God" He did his best to try to grind us into the ground...Luckily Hillary didn't get to finish the job!

Short Excerpt Teaser

PrologueIt's been almost ten years since I first ran for political office. I was thirty-five at the time, four years out of law school, recently married, and generally impatient with life. A seat in the Illinois legislature had opened up, and several friends suggested that I run, thinking that my work as a civil rights lawyer, and contacts from my days as a community organizer, would make me a viable candidate. After discussing it with my wife, I entered the race and proceeded to do what every first-time candidate does: I talked to anyone who would listen. I went to block club meetings and church socials, beauty shops and barbershops. If two guys were standing on a corner, I would cross the street to hand them campaign literature. And everywhere I went, I'd get some version of the same two questions."Where'd you get that funny name?"And then: "You seem like a nice enough guy. Why do you want to go into something dirty and nasty like politics?"I was familiar with the question, a variant on the questions asked of me years earlier, when I'd first arrived in Chicago to work in low-income neighborhoods. It signaled a cynicism not simply with politics but with the very notion of a public life, a cynicism that–at least in the South Side neighborhoods I sought to represent–had been nourished by a generation of broken promises. In response, I would usually smile and nod and say that I understood the skepticism, but that there was–and always had been–another tradition to politics, a tradition that stretched from the days of the country's founding to the glory of the civil rights movement, a tradition based on the simple idea that we have a stake in one another, and that what binds us together is greater than what drives us apart, and that if enough people believe in the truth of that proposition and act on it, then we might not solve every problem, but we can get something meaningful done. It was a pretty convincing speech, I thought. And although I'm not sure that the people who heard me deliver it were similarly impressed, enough of them appreciated my earnestness and youthful swagger that I made it to the Illinois legislature.Six years later, when I decided to run for the United States Senate, I wasn't so sure of myself.By all appearances, my choice of careers seemed to have worked out. After spending my two terms during which I labored in the minority, Democrats had gained control of the state senate, and I had subsequently passed a slew of bills, from reforms of the Illinois death penalty system to an expansion of the state's health program for kids. I had continued to teach at the University of Chicago Law School, a job I enjoyed, and was frequently invited to speak around town. I had preserved my independence, my good name, and my marriage, all of which, statistically speaking, had been placed at risk the moment I set foot in the state capital.But the years had also taken their toll. Some of it was just a function of my getting older, I suppose, for if you are paying attention, each successive year will make you more intimately acquainted with all of your flaws–the blind spots, the recurring habits of thought that may be genetic or may be environmental, but that will almost certainly worsen with time, as surely as the hitch in your walk turns to pain in your hip. In me, one of those flaws had proven to be a chronic restlessness; an inability to appreciate, no matter how well things were going, those blessings that were right there in front of me. It's a flaw that is endemic to modern life, I think–endemic, too, in the American character–and one that is nowhere more evident than in the field of politics. Whether politics actually encourages the trait or simply attracts those who possess it is unclear. Lyndon Johnson, who knew much about both politics and restlessness, once said that every man is trying to either live up to his father's expectations or make up for his father's mistakes, and I suppose that may explain my particular malady as well as anything else.In any event, it was as a consequence of that restlessness that I decided to challenge a sitting Democratic incumbent for his congressional seat in the 2000 election cycle. It was an ill-considered race, and I lost badly–the sort of drubbing that awakens you to the fact that life is not obliged to work out as you'd planned. A year and a half later, the scars of that loss sufficiently healed, I had lunch with a media consultant who had been encouraging me for some time to run for statewide office. As it happened, the lunch was scheduled for late September 2001."You realize, don't you, that the political dynamics have changed," he said as he picked at his salad."What do you mean?" I asked, knowing full well what he meant. We both looked down at the newspaper beside him. There, on the front page, w...