Literature & Fiction

- Publisher : Random House

- Published : 20 Sep 2022

- Pages : 448

- ISBN-10 : 0593448642

- ISBN-13 : 9780593448649

- Language : English

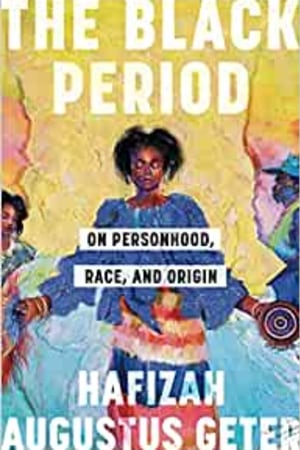

The Black Period: On Personhood, Race, and Origin

An acclaimed poet reclaims her origin story as the queer daughter of a Muslim Nigerian immigrant and a Black American visual artist in this groundbreaking memoir, combining lyrical prose, biting criticism, and haunting visuals.

"Hafizah Augustus Geter is a genuine artist, not bound by genre or form. Her only loyalty is the harrowing beauty of the truth."-Tayari Jones, author of An American Marriage

"I say, ‘the Black Period,' and mean ‘home' in all its shapeshifting ways." In The Black Period, Hafizah creates a space for the beauty of Blackness, Islam, disability, and queerness to flourish, celebrating the many layers of her existence that America has time and again sought to erase.

At nineteen, she lost her mother to a sudden stroke. Weeks later, her father became so heartsick that he needed a triple bypass. By her thirties, she was constantly in pain, pinballing between physical therapy appointments, her grief, and the grind that is the American Dream. Hafizah realized she'd spent years internalizing the narratives that white supremacy had fed her about herself. Suddenly, she says, I was standing at the cliff of my own life, remembering.

Recalling her parents' lessons on the art of Black revision, and mixing history, political analysis, and cultural criticism, alongside stunning original artwork created by her father, renowned artist Tyrone Geter, Hafizah maps out her own narrative, weaving between a childhood populated with Southern and Nigerian relatives; her days in a small Catholic school; a loving but tragically short relationship with her mother; and the feelings of joy and community that the Black Lives Matter protests engendered in her as an adult. All throughout, she forms a new personal and collective history, addressing the systems of inequity that make life difficult for non-able-bodied persons, queer people, and communities of color while capturing a world brimming with potential, art, music, hope, and love.

A unique combination of gripping memoir and Afrofuturist thought, in The Black Period, Hafizah manages to sidestep shame, confront disability, embrace forgiveness, and emerge from the erasures America imposes to exist proudly and unabashedly as herself.

"Hafizah Augustus Geter is a genuine artist, not bound by genre or form. Her only loyalty is the harrowing beauty of the truth."-Tayari Jones, author of An American Marriage

"I say, ‘the Black Period,' and mean ‘home' in all its shapeshifting ways." In The Black Period, Hafizah creates a space for the beauty of Blackness, Islam, disability, and queerness to flourish, celebrating the many layers of her existence that America has time and again sought to erase.

At nineteen, she lost her mother to a sudden stroke. Weeks later, her father became so heartsick that he needed a triple bypass. By her thirties, she was constantly in pain, pinballing between physical therapy appointments, her grief, and the grind that is the American Dream. Hafizah realized she'd spent years internalizing the narratives that white supremacy had fed her about herself. Suddenly, she says, I was standing at the cliff of my own life, remembering.

Recalling her parents' lessons on the art of Black revision, and mixing history, political analysis, and cultural criticism, alongside stunning original artwork created by her father, renowned artist Tyrone Geter, Hafizah maps out her own narrative, weaving between a childhood populated with Southern and Nigerian relatives; her days in a small Catholic school; a loving but tragically short relationship with her mother; and the feelings of joy and community that the Black Lives Matter protests engendered in her as an adult. All throughout, she forms a new personal and collective history, addressing the systems of inequity that make life difficult for non-able-bodied persons, queer people, and communities of color while capturing a world brimming with potential, art, music, hope, and love.

A unique combination of gripping memoir and Afrofuturist thought, in The Black Period, Hafizah manages to sidestep shame, confront disability, embrace forgiveness, and emerge from the erasures America imposes to exist proudly and unabashedly as herself.

Editorial Reviews

Chapter 1

Reverberation, Reverberation

AGE I

The Body

I stare out at the Grand Canyon's Precambrian rock, searching for the oldest way to know a country. Red cliffs thrust into vanishing violets. Some borrow the blue of the sky. This canyon aches inside me. My wife, Stephanie, my best friend Camille-her belly at the end of its first trimester-Andrey, her Belarusian husband, and I have come to see the rarest thing of all: a beginning. Have come in search of a reminder that beyond these bodies, we are rock, river, gully. Though, too, we are a fee we've paid the U.S. government to access once-sovereign sites of emergence for the Hualapai, Havsuw 'Baaja, Hopi, Yavapai-Apache, Diné, Zuni, and Paiute Nations-as a small plaque, designed to be barely visible in our minds, tells us.

Across their kidnapped landscape, white cliffrose and pink Apache plume bloom. Moss, green and purplish shrubs patch the expanse. Shale, sand, and limestone glimmer in the March sun. The Grand Canyon is something both brand-new and familiar, like the hues my father used in the children's books he illustrated me and my sister, Jamila, into-it's like holding each of my nephews for the very first time. Above, the clouds ink up every color. I consider the status of my back. It's been a decade of chiropractors, cortisol shots, these invisible bricks the size of my country that live at my back, neck, and shoulders. Pain has lived in me, with me so long, I no longer name it.

Unlike our white partners, Camille and I have never been to this part of America before. This 1,902-square-mile canyon stretching out in front of us is so beautiful it veers on incomprehensible. Called Ongtupqa by the Hopi, Bidááʼ Haʼaztʼiʼ Tsékooh by the Diné, and Wi:kaʼi:la by the Yavapai, the white colonizers first referred to it as "The Great Unknown." They drew it as a literal blank spot on their maps, but my father would paint this scene blue-violet, paint it into the in-betweens of color to remind me that value, a gradient between light and dark, is an interpretation by the hand of the creator.

My father would say: They can't even look over their shoulders and find a hero. A man aging more and more into non sequiturs, I know he means truth, legacy, and white people. He means beginnings and us. When my father speaks of beginnings, he means this nation is a dangerous place to be stuck. A bad beginning, he's warned me, can make you mistake treading water for swimming. It can be the wrong end of a stick, while the right beginning can be a rescue.

Gazing out at one origin, I find it impossible not to consider the end of mine. My father came home on his lunch break to catch my mother in his arms as she died from a single massive stroke. Her brain burst like a co...

Reverberation, Reverberation

AGE I

The Body

I stare out at the Grand Canyon's Precambrian rock, searching for the oldest way to know a country. Red cliffs thrust into vanishing violets. Some borrow the blue of the sky. This canyon aches inside me. My wife, Stephanie, my best friend Camille-her belly at the end of its first trimester-Andrey, her Belarusian husband, and I have come to see the rarest thing of all: a beginning. Have come in search of a reminder that beyond these bodies, we are rock, river, gully. Though, too, we are a fee we've paid the U.S. government to access once-sovereign sites of emergence for the Hualapai, Havsuw 'Baaja, Hopi, Yavapai-Apache, Diné, Zuni, and Paiute Nations-as a small plaque, designed to be barely visible in our minds, tells us.

Across their kidnapped landscape, white cliffrose and pink Apache plume bloom. Moss, green and purplish shrubs patch the expanse. Shale, sand, and limestone glimmer in the March sun. The Grand Canyon is something both brand-new and familiar, like the hues my father used in the children's books he illustrated me and my sister, Jamila, into-it's like holding each of my nephews for the very first time. Above, the clouds ink up every color. I consider the status of my back. It's been a decade of chiropractors, cortisol shots, these invisible bricks the size of my country that live at my back, neck, and shoulders. Pain has lived in me, with me so long, I no longer name it.

Unlike our white partners, Camille and I have never been to this part of America before. This 1,902-square-mile canyon stretching out in front of us is so beautiful it veers on incomprehensible. Called Ongtupqa by the Hopi, Bidááʼ Haʼaztʼiʼ Tsékooh by the Diné, and Wi:kaʼi:la by the Yavapai, the white colonizers first referred to it as "The Great Unknown." They drew it as a literal blank spot on their maps, but my father would paint this scene blue-violet, paint it into the in-betweens of color to remind me that value, a gradient between light and dark, is an interpretation by the hand of the creator.

My father would say: They can't even look over their shoulders and find a hero. A man aging more and more into non sequiturs, I know he means truth, legacy, and white people. He means beginnings and us. When my father speaks of beginnings, he means this nation is a dangerous place to be stuck. A bad beginning, he's warned me, can make you mistake treading water for swimming. It can be the wrong end of a stick, while the right beginning can be a rescue.

Gazing out at one origin, I find it impossible not to consider the end of mine. My father came home on his lunch break to catch my mother in his arms as she died from a single massive stroke. Her brain burst like a co...

Short Excerpt Teaser

Chapter 1

Reverberation, Reverberation

AGE I

The Body

I stare out at the Grand Canyon's Precambrian rock, searching for the oldest way to know a country. Red cliffs thrust into vanishing violets. Some borrow the blue of the sky. This canyon aches inside me. My wife, Stephanie, my best friend Camille-her belly at the end of its first trimester-Andrey, her Belarusian husband, and I have come to see the rarest thing of all: a beginning. Have come in search of a reminder that beyond these bodies, we are rock, river, gully. Though, too, we are a fee we've paid the U.S. government to access once-sovereign sites of emergence for the Hualapai, Havsuw 'Baaja, Hopi, Yavapai-Apache, Diné, Zuni, and Paiute Nations-as a small plaque, designed to be barely visible in our minds, tells us.

Across their kidnapped landscape, white cliffrose and pink Apache plume bloom. Moss, green and purplish shrubs patch the expanse. Shale, sand, and limestone glimmer in the March sun. The Grand Canyon is something both brand-new and familiar, like the hues my father used in the children's books he illustrated me and my sister, Jamila, into-it's like holding each of my nephews for the very first time. Above, the clouds ink up every color. I consider the status of my back. It's been a decade of chiropractors, cortisol shots, these invisible bricks the size of my country that live at my back, neck, and shoulders. Pain has lived in me, with me so long, I no longer name it.

Unlike our white partners, Camille and I have never been to this part of America before. This 1,902-square-mile canyon stretching out in front of us is so beautiful it veers on incomprehensible. Called Ongtupqa by the Hopi, Bidááʼ Haʼaztʼiʼ Tsékooh by the Diné, and Wi:kaʼi:la by the Yavapai, the white colonizers first referred to it as "The Great Unknown." They drew it as a literal blank spot on their maps, but my father would paint this scene blue-violet, paint it into the in-betweens of color to remind me that value, a gradient between light and dark, is an interpretation by the hand of the creator.

My father would say: They can't even look over their shoulders and find a hero. A man aging more and more into non sequiturs, I know he means truth, legacy, and white people. He means beginnings and us. When my father speaks of beginnings, he means this nation is a dangerous place to be stuck. A bad beginning, he's warned me, can make you mistake treading water for swimming. It can be the wrong end of a stick, while the right beginning can be a rescue.

Gazing out at one origin, I find it impossible not to consider the end of mine. My father came home on his lunch break to catch my mother in his arms as she died from a single massive stroke. Her brain burst like a colossal star. I was a sophomore in college. Now, she's been gone so long, is all that's left of her, her propagation? Me, my sister, the grandchildren she loves but will never meet or know.

I don't see the capital of the Havasupai Indian Reservation, the village of Supai, at the base of the canyon. I'm too far away to see the fresh footprints on their ancestral footpaths. Still, I know, like all Indigenous peoples, the Havsuw 'Baaja have to fight for their ancestral lands inside the young laws of illegitimate governments. They have had to take "beginnings" to court, despite having called the base of the canyon home since AD 1300. For both Native and Black folks, white America tries to legislate the start of our narratives, overwriting our beginnings with "manifest destiny," smiling slaves, mascots, in classrooms-on TV, in history and children's books-and through marginalizing tactics like redlining, censorship, and incarceration and policing. This need to guard our origin stories I recognize as one of the many things our people have in common.

"We didn't ask to be put on a reservation . . . [this] was imposed on us," Coleen Kaska, a former Havasupai tribal council member, tells a reporter in 2017, reminding me of the 1964 Malcolm that so many of the Black adults of my childhood loved to shout: "We didn't land on Plymouth Rock! The rock was landed on us!"

Kaska, whose parents taught her that her duty was "to grow up and pursue the lands that we have lost."

But I won't read Kaska's words until months later when I finally google this place I've come to so easily, not knowing much of anything about it. For now, from our vantage point, it is easy to assume that there is no one here but us.

The Havsuw 'Baaja are "the Blue Creek people," named the Havasupai tribe by the federal government. They are the first people documented in North America, more than twenty thousand years ago, and their language is suspected to be the first spoken in t...

Reverberation, Reverberation

AGE I

The Body

I stare out at the Grand Canyon's Precambrian rock, searching for the oldest way to know a country. Red cliffs thrust into vanishing violets. Some borrow the blue of the sky. This canyon aches inside me. My wife, Stephanie, my best friend Camille-her belly at the end of its first trimester-Andrey, her Belarusian husband, and I have come to see the rarest thing of all: a beginning. Have come in search of a reminder that beyond these bodies, we are rock, river, gully. Though, too, we are a fee we've paid the U.S. government to access once-sovereign sites of emergence for the Hualapai, Havsuw 'Baaja, Hopi, Yavapai-Apache, Diné, Zuni, and Paiute Nations-as a small plaque, designed to be barely visible in our minds, tells us.

Across their kidnapped landscape, white cliffrose and pink Apache plume bloom. Moss, green and purplish shrubs patch the expanse. Shale, sand, and limestone glimmer in the March sun. The Grand Canyon is something both brand-new and familiar, like the hues my father used in the children's books he illustrated me and my sister, Jamila, into-it's like holding each of my nephews for the very first time. Above, the clouds ink up every color. I consider the status of my back. It's been a decade of chiropractors, cortisol shots, these invisible bricks the size of my country that live at my back, neck, and shoulders. Pain has lived in me, with me so long, I no longer name it.

Unlike our white partners, Camille and I have never been to this part of America before. This 1,902-square-mile canyon stretching out in front of us is so beautiful it veers on incomprehensible. Called Ongtupqa by the Hopi, Bidááʼ Haʼaztʼiʼ Tsékooh by the Diné, and Wi:kaʼi:la by the Yavapai, the white colonizers first referred to it as "The Great Unknown." They drew it as a literal blank spot on their maps, but my father would paint this scene blue-violet, paint it into the in-betweens of color to remind me that value, a gradient between light and dark, is an interpretation by the hand of the creator.

My father would say: They can't even look over their shoulders and find a hero. A man aging more and more into non sequiturs, I know he means truth, legacy, and white people. He means beginnings and us. When my father speaks of beginnings, he means this nation is a dangerous place to be stuck. A bad beginning, he's warned me, can make you mistake treading water for swimming. It can be the wrong end of a stick, while the right beginning can be a rescue.

Gazing out at one origin, I find it impossible not to consider the end of mine. My father came home on his lunch break to catch my mother in his arms as she died from a single massive stroke. Her brain burst like a colossal star. I was a sophomore in college. Now, she's been gone so long, is all that's left of her, her propagation? Me, my sister, the grandchildren she loves but will never meet or know.

I don't see the capital of the Havasupai Indian Reservation, the village of Supai, at the base of the canyon. I'm too far away to see the fresh footprints on their ancestral footpaths. Still, I know, like all Indigenous peoples, the Havsuw 'Baaja have to fight for their ancestral lands inside the young laws of illegitimate governments. They have had to take "beginnings" to court, despite having called the base of the canyon home since AD 1300. For both Native and Black folks, white America tries to legislate the start of our narratives, overwriting our beginnings with "manifest destiny," smiling slaves, mascots, in classrooms-on TV, in history and children's books-and through marginalizing tactics like redlining, censorship, and incarceration and policing. This need to guard our origin stories I recognize as one of the many things our people have in common.

"We didn't ask to be put on a reservation . . . [this] was imposed on us," Coleen Kaska, a former Havasupai tribal council member, tells a reporter in 2017, reminding me of the 1964 Malcolm that so many of the Black adults of my childhood loved to shout: "We didn't land on Plymouth Rock! The rock was landed on us!"

Kaska, whose parents taught her that her duty was "to grow up and pursue the lands that we have lost."

But I won't read Kaska's words until months later when I finally google this place I've come to so easily, not knowing much of anything about it. For now, from our vantage point, it is easy to assume that there is no one here but us.

The Havsuw 'Baaja are "the Blue Creek people," named the Havasupai tribe by the federal government. They are the first people documented in North America, more than twenty thousand years ago, and their language is suspected to be the first spoken in t...