Historical

- Publisher : Crown

- Published : 21 Feb 2023

- Pages : 304

- ISBN-10 : 0593135687

- ISBN-13 : 9780593135686

- Language : English

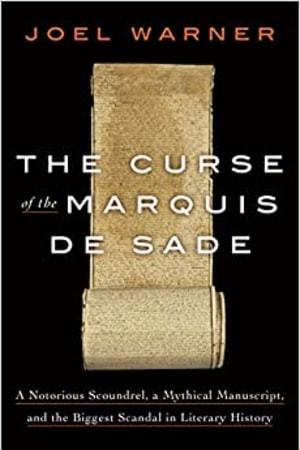

The Curse of the Marquis de Sade: A Notorious Scoundrel, a Mythical Manuscript, and the Biggest Scandal in Literary History

The captivating, deeply reported true story of how one of the most notorious novels ever written-Marquis de Sade's 120 Days of Sodom-landed at the heart of one of the biggest scams in modern literary history.

"Reading The Curse of the Marquis de Sade, with the Marquis, the sabotage of rare manuscript sales, and a massive Ponzi scheme at its center,felt like a twisty waterslide shooting through a sleazy and bizarre landscape. This book is wild."-Adam McKay, Academy Award–winning filmmaker

Described as both "one of the most important novels ever written" and "the gospel of evil," 120 Days of Sodom was written by the Marquis de Sade, a notorious eighteenth-century aristocrat who waged a campaign of mayhem and debauchery across France, evaded execution, and inspired the word "sadism," which came to mean receiving pleasure from pain. Despite all his crimes, Sade considered this work to be his greatest transgression.

The original manuscript of 120 Days of Sodom, a tiny scroll penned in the bowels of the Bastille in Paris, would embark on a centuries-spanning odyssey across Europe, passing from nineteenth-century banned book collectors to pioneering sex researchers to avant-garde artists before being hidden away from Nazi book burnings. In 2014, the world heralded its return to France when the scroll was purchased for millions by Gérard Lhéritier, the self-made son of a plumber who had used his savvy business skills to upend France's renowned rare-book market. But the sale opened the door to vendettas by the government, feuds among antiquarian booksellers, manuscript sales derailed by sabotage, a record-breaking lottery jackpot, and allegations of a decade-long billion-euro con, the specifics of which, if true, would make the scroll part of France's largest-ever Ponzi scheme.

Told with gripping reporting and flush with deceit and scandal, The Curse of the Marquis de Sade weaves together the sweeping odyssey of 120 Days of Sodom and the spectacular rise and fall of Lhéritier, once the "king of manuscripts" and now known to many as the Bernie Madoff of France. At its center is an urgent question for all those who cherish the written word: As the age of handwriting comes to an end, what do we owe the original texts left behind?

"Reading The Curse of the Marquis de Sade, with the Marquis, the sabotage of rare manuscript sales, and a massive Ponzi scheme at its center,felt like a twisty waterslide shooting through a sleazy and bizarre landscape. This book is wild."-Adam McKay, Academy Award–winning filmmaker

Described as both "one of the most important novels ever written" and "the gospel of evil," 120 Days of Sodom was written by the Marquis de Sade, a notorious eighteenth-century aristocrat who waged a campaign of mayhem and debauchery across France, evaded execution, and inspired the word "sadism," which came to mean receiving pleasure from pain. Despite all his crimes, Sade considered this work to be his greatest transgression.

The original manuscript of 120 Days of Sodom, a tiny scroll penned in the bowels of the Bastille in Paris, would embark on a centuries-spanning odyssey across Europe, passing from nineteenth-century banned book collectors to pioneering sex researchers to avant-garde artists before being hidden away from Nazi book burnings. In 2014, the world heralded its return to France when the scroll was purchased for millions by Gérard Lhéritier, the self-made son of a plumber who had used his savvy business skills to upend France's renowned rare-book market. But the sale opened the door to vendettas by the government, feuds among antiquarian booksellers, manuscript sales derailed by sabotage, a record-breaking lottery jackpot, and allegations of a decade-long billion-euro con, the specifics of which, if true, would make the scroll part of France's largest-ever Ponzi scheme.

Told with gripping reporting and flush with deceit and scandal, The Curse of the Marquis de Sade weaves together the sweeping odyssey of 120 Days of Sodom and the spectacular rise and fall of Lhéritier, once the "king of manuscripts" and now known to many as the Bernie Madoff of France. At its center is an urgent question for all those who cherish the written word: As the age of handwriting comes to an end, what do we owe the original texts left behind?

Editorial Reviews

"Fans of John Carreyrou's Bad Blood or Billion Dollar Loser by Reeves Wiedeman will probably enjoy the final thread of The Curse of the Marquis de Sade. . . . Warner excels at explaining Lhéritier's complex-and possibly criminal-business operations in easy-to-understand language. And his depiction of France's lively rare-manuscript community is a fascinating look at a largely hidden subculture."-Washington Post

"Lively. . . . Aristophil's downfall reads like the best kind of business thriller. . . . Warner writes like a man having fun with his subject."-The Times

"Warner's research and extensive interviews help him shuttle across centuries to depict remarkable characters. . . . Warner doesn't let infamy flatten Sade's dimensions."-New York Times Book Review

"A fascinating literary scandal. . . . a strange and fantastical journey involving a level of criminality that rivaled the life of Sade himself."-Slate

"Fascinating."-Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star

"Dazzling. . . . Warner's story is a tightly woven braid of three connected themes: a history of the racier aspects of European bibliophilia, a morality tale about rapacity in the art world of recent history, and, finally, the life, work and changing reputation of Sade himself."-The Telegraph

"Compelling. . . . So rich in detail. . . . Obviously meticulously researched."-The Colorado Sun

"Illuminating. . . . The wealth of detail never slows Warner's well-paced narrative. Literary history buffs will want to check this out."-Publishers Weekly

"An engrossing history of the travels of a notorious manuscript across nations and centuries"-Kirkus Reviews

"Joel Warner has written the best kind of history, making the past seem present with wonderful and outrageous characters, a story that jumps propulsively between eras, and ...

"Lively. . . . Aristophil's downfall reads like the best kind of business thriller. . . . Warner writes like a man having fun with his subject."-The Times

"Warner's research and extensive interviews help him shuttle across centuries to depict remarkable characters. . . . Warner doesn't let infamy flatten Sade's dimensions."-New York Times Book Review

"A fascinating literary scandal. . . . a strange and fantastical journey involving a level of criminality that rivaled the life of Sade himself."-Slate

"Fascinating."-Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star

"Dazzling. . . . Warner's story is a tightly woven braid of three connected themes: a history of the racier aspects of European bibliophilia, a morality tale about rapacity in the art world of recent history, and, finally, the life, work and changing reputation of Sade himself."-The Telegraph

"Compelling. . . . So rich in detail. . . . Obviously meticulously researched."-The Colorado Sun

"Illuminating. . . . The wealth of detail never slows Warner's well-paced narrative. Literary history buffs will want to check this out."-Publishers Weekly

"An engrossing history of the travels of a notorious manuscript across nations and centuries"-Kirkus Reviews

"Joel Warner has written the best kind of history, making the past seem present with wonderful and outrageous characters, a story that jumps propulsively between eras, and ...

Readers Top Reviews

Diane Ha delicate

A real-life history of both the Marquis de Sade and the twisted story of his long-lost manuscript sounds like an intriguing tale. However, the organization of The Curse of the Marquis de Sade was so confusing, it was a hard book to read. If you don’t know already, de Sade was a blatant sexual predator who preyed on sex workers and the young. That alone will set off many readers’ triggers. However, if you are already interested in him, the subject, the time period, or old manuscripts, you might enjoy reading The Curse of the Marquis de Sade. To each their own, but for me the book receives 3 stars. Thanks to Crown Publishing and NetGalley for a digital review copy of the book.

Short Excerpt Teaser

The Scroll

Chapter One

Relic of Freedom

July 14, 1789

The summer sky above Paris hung heavy with clouds as a plume of smoke rose east of the city center. The scent of gunpowder wafted through the muggy afternoon air, while the crackle of musket fire and battle yells echoed through the cobblestoned streets.

Four years had passed since Sade had written 120 Days of Sodom. Beyond the walls of the Bastille, the world carried on in one of the largest cities in Europe, a crowded metropolis of 810 streets and twenty-three thousand houses that more than a half million people called home. By many measures, by the late 1780s Paris had come a long way toward achieving Louis XIV's declaration a century before that the French capital should rival the glories of ancient Rome. The old walls that ringed the city had come down, replaced by victory arches and graceful boulevards. The bridges over the Seine had been cleared of the medieval houses that had clogged their thoroughfares and left them on the verge of collapse. Colossal new public squares like the Place Vendôme and the Place de la Concorde provided the capital with new civic spaces, while a long stretch of open fields and kitchen gardens on the city's western fringe had been transformed into a grand boulevard called the Champs-Élysées. In posh suburban neighborhoods like the Faubourg Saint-Honoré and the Faubourg Saint-Germain, palatial mansions had gone up to house the swelling number of wealthy bourgeois, boasting recently minted fortunes and new noble titles awarded or sold to them by the crown.

But in the cramped center of the city, conditions remained intolerable. The maze of dark, narrow streets festered with filth and crime, barely penetrated by the réverbères, or metal oil lamps, installed throughout the capital. On either side of muddy lanes, in shabby row houses of wood, limestone, and plaster that reached four, five, and six stories high, the families of Paris's servants, laborers, and artisans crammed into three-room apartments, many of which lacked a dedicated kitchen, much less a toilet or bath.

Recently city dwellers had seen the price of bread, the main staple of their meager diets, consume an ever-larger portion of their shrinking incomes as years of costly wars, poor harvests, and the timid leadership of the current monarch, King Louis XVI, led to financial crises. Desperate measures by the crown, such as a new wall around Paris to enforce tolls on goods entering the city and a trade agreement that allowed British goods to flood the market, plunged the nation further into debt. Many lost their jobs, and nearly two hundred thousand Parisians came to depend on religious assistance or government handouts. As the drought-ravaged fields around the city deteriorated, troops patrolled the markets to deter riots over bread. And as radical new philosophical movements championed egalitarianism and an upstart middle class jockeyed for political power, the people watched the nobility continue to revel in opulence.

The final provocation had arrived that summer. An attempt by the king to raise revenues and quell dissent by summoning a convention of the Estates General, an assembly of representatives from the country's various social classes, had collapsed amid political infighting over who should have the most say in the nation's affairs. Struggling to afford food and fearful of an aristocratic conspiracy to undermine the middle and lower classes, commoners had taken to the streets. Factories and wealthy monasteries were ransacked, and most of the new customhouses at the city's toll gates were burned to the ground. Around the city, army regiments moved into battle positions.

With rumors spreading of a crackdown, Parisians girded for battle. Theaters and cafés shuttered their doors, and the call went out to erect barricades, gather provisions, and, most important, marshal arms. Early that rainy morning, a mob of citizens raided the army barracks at the Invalides military hospital, coming away with thousands of rifles and several cannons, but very little ammunition. Hundreds of barrels of gunpowder, they learned, were being stored elsewhere: in the Bastille.

The gray stone hulk's eight medieval towers dominated the city skyline and loomed large in the public's imagination. This was where numerous state convicts had rotted away, including the legendary Man in the Iron Mask, a mysterious criminal forced to hide his face and who would eventually die in his cell before anyone could uncover his identity. Tales of prisoners emerging from the citadel fueled a cottage publishing industry, generating page-turners detailing filthy cells, dangerously inadequate rations, and corpse-filled subterranean dungeons. And ...

Chapter One

Relic of Freedom

July 14, 1789

The summer sky above Paris hung heavy with clouds as a plume of smoke rose east of the city center. The scent of gunpowder wafted through the muggy afternoon air, while the crackle of musket fire and battle yells echoed through the cobblestoned streets.

Four years had passed since Sade had written 120 Days of Sodom. Beyond the walls of the Bastille, the world carried on in one of the largest cities in Europe, a crowded metropolis of 810 streets and twenty-three thousand houses that more than a half million people called home. By many measures, by the late 1780s Paris had come a long way toward achieving Louis XIV's declaration a century before that the French capital should rival the glories of ancient Rome. The old walls that ringed the city had come down, replaced by victory arches and graceful boulevards. The bridges over the Seine had been cleared of the medieval houses that had clogged their thoroughfares and left them on the verge of collapse. Colossal new public squares like the Place Vendôme and the Place de la Concorde provided the capital with new civic spaces, while a long stretch of open fields and kitchen gardens on the city's western fringe had been transformed into a grand boulevard called the Champs-Élysées. In posh suburban neighborhoods like the Faubourg Saint-Honoré and the Faubourg Saint-Germain, palatial mansions had gone up to house the swelling number of wealthy bourgeois, boasting recently minted fortunes and new noble titles awarded or sold to them by the crown.

But in the cramped center of the city, conditions remained intolerable. The maze of dark, narrow streets festered with filth and crime, barely penetrated by the réverbères, or metal oil lamps, installed throughout the capital. On either side of muddy lanes, in shabby row houses of wood, limestone, and plaster that reached four, five, and six stories high, the families of Paris's servants, laborers, and artisans crammed into three-room apartments, many of which lacked a dedicated kitchen, much less a toilet or bath.

Recently city dwellers had seen the price of bread, the main staple of their meager diets, consume an ever-larger portion of their shrinking incomes as years of costly wars, poor harvests, and the timid leadership of the current monarch, King Louis XVI, led to financial crises. Desperate measures by the crown, such as a new wall around Paris to enforce tolls on goods entering the city and a trade agreement that allowed British goods to flood the market, plunged the nation further into debt. Many lost their jobs, and nearly two hundred thousand Parisians came to depend on religious assistance or government handouts. As the drought-ravaged fields around the city deteriorated, troops patrolled the markets to deter riots over bread. And as radical new philosophical movements championed egalitarianism and an upstart middle class jockeyed for political power, the people watched the nobility continue to revel in opulence.

The final provocation had arrived that summer. An attempt by the king to raise revenues and quell dissent by summoning a convention of the Estates General, an assembly of representatives from the country's various social classes, had collapsed amid political infighting over who should have the most say in the nation's affairs. Struggling to afford food and fearful of an aristocratic conspiracy to undermine the middle and lower classes, commoners had taken to the streets. Factories and wealthy monasteries were ransacked, and most of the new customhouses at the city's toll gates were burned to the ground. Around the city, army regiments moved into battle positions.

With rumors spreading of a crackdown, Parisians girded for battle. Theaters and cafés shuttered their doors, and the call went out to erect barricades, gather provisions, and, most important, marshal arms. Early that rainy morning, a mob of citizens raided the army barracks at the Invalides military hospital, coming away with thousands of rifles and several cannons, but very little ammunition. Hundreds of barrels of gunpowder, they learned, were being stored elsewhere: in the Bastille.

The gray stone hulk's eight medieval towers dominated the city skyline and loomed large in the public's imagination. This was where numerous state convicts had rotted away, including the legendary Man in the Iron Mask, a mysterious criminal forced to hide his face and who would eventually die in his cell before anyone could uncover his identity. Tales of prisoners emerging from the citadel fueled a cottage publishing industry, generating page-turners detailing filthy cells, dangerously inadequate rations, and corpse-filled subterranean dungeons. And ...