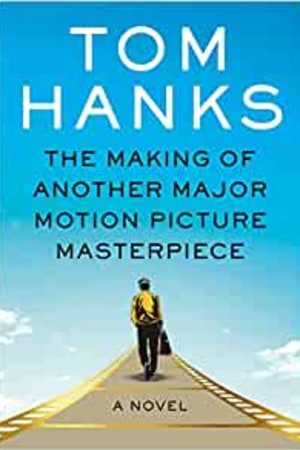

Genre Fiction

- Publisher : Knopf

- Published : 09 May 2023

- Pages : 448

- ISBN-10 : 052565559X

- ISBN-13 : 9780525655596

- Language : English

The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece: A novel

From the legendary actor and best-selling author: a novel about the making of a star-studded, multimillion-dollar superhero action film...and the humble comic books that inspired it. Funny, touching, and wonderfully thought-provoking, while also capturing the changes in America and American culture since World War II.

"Wild, ambitious and exceptionally enjoyable." -Matt Haig, best-selling author The Midnight Library, The Humans and Reasons to Stay Alive

Part One of this story takes place in 1947. A troubled soldier, returning from the war, meets his talented five-year-old nephew, leaves an indelible impression, and then disappears for twenty-three years.

Cut to 1970: The nephew, now drawing underground comic books in Oakland, California, reconnects with his uncle and, remembering the comic book he saw when he was five, draws a new version with his uncle as a World War II fighting hero.

Cut to the present day: A commercially successful director discovers the 1970 comic book and decides to turn it into a contemporary superhero movie.

Cue the cast: We meet the film's extremely difficult male star, his wonderful leading lady, the eccentric writer/director, the producer, the gofer production assistant, and everyone else on both sides of the camera.

Bonus material: Interspersed throughout are three comic books that are featured in the story-all created by Tom Hanks himself-including the comic book that becomes the official tie-in to this novel's "major motion picture masterpiece."

"Wild, ambitious and exceptionally enjoyable." -Matt Haig, best-selling author The Midnight Library, The Humans and Reasons to Stay Alive

Part One of this story takes place in 1947. A troubled soldier, returning from the war, meets his talented five-year-old nephew, leaves an indelible impression, and then disappears for twenty-three years.

Cut to 1970: The nephew, now drawing underground comic books in Oakland, California, reconnects with his uncle and, remembering the comic book he saw when he was five, draws a new version with his uncle as a World War II fighting hero.

Cut to the present day: A commercially successful director discovers the 1970 comic book and decides to turn it into a contemporary superhero movie.

Cue the cast: We meet the film's extremely difficult male star, his wonderful leading lady, the eccentric writer/director, the producer, the gofer production assistant, and everyone else on both sides of the camera.

Bonus material: Interspersed throughout are three comic books that are featured in the story-all created by Tom Hanks himself-including the comic book that becomes the official tie-in to this novel's "major motion picture masterpiece."

Editorial Reviews

1 Backstory

A little over five years back, I had a message on my voice mail from one Al Mac-Teer-which I heard as Almick Tear-from a number in the 310 area code. This no-nonsense woman asked me to call her back regarding a thin little memoir I had written called A Stairway Down to Heaven about my years of tending bar in a small subterranean club that played live music way back in the '80s. At the time, I was also, sort of, a freelance journalist in and around Pittsburgh, PA. And I wrote movie reviews. These days I teach Creative Writing, Common Literature, and Film Studies at Mount Chisholm College of the Arts in the hills of Montana. Bozeman is a gorgeous if stark drive away. I get very few voice mails from Los Angeles, California.

"My boss read your memoir," Ms. Mac-Teer told me. "He says you write like he thinks."

"Your boss is brilliant," I told her, then asked, "Who is your boss?" When she told me she worked for Bill Johnson, that I had reached her on her cell as she was driving from her home in Santa Monica to her office in the Capitol Records Building in Hollywood for a meeting with him, I hollered, "You work for Bi-Bi-Bi-Bill JOHNSON? The movie director? Prove it."

Some days later, I was on the phone with Bi-Bi-Bi-Bill Johnson himself, and we were talking about his line of work, one of the subjects I teach. When I told him I'd seen his entire filmography, he accused me of blowing smoke. When I rattled off many salient points from his movies, he told me to shut up, enough already. At that time, he was "noodling" a screenplay about music in the transformative years of the '60s going into the '70s-when bands evolved from matching outfits and three-minute songs for AM radio to LP side-long jams and the Jimi Hendrix Experience. The stories from my book were full of very personal details. Even though my era was twenty years after what he was "noodling"-our club booked unheralded jazz combos and Depeche Mode cover bands-the stuff that happens in live-music venues is timeless, universal. The fights, the drugs, the serious love, the fun sex, the fun love, the serious sex, the laughs and the screaming, the Who-Gets-In and Who-Gets-Bounced-the whole riotous scene of procedures both spoken and intuitive-were the human behaviors that he wanted to nail. He offered me money for my book-the nonexclusive rights to my story, meaning I could still sell the exclusive rights, if there should ever be an offer. Fat chance. Still, I made more money selling him the rights to my book than I did selling copies of the thing.

Bill went off to film Pocket Rockets but kept up with me through calls and many typewritten letters-missives of wandering topics, his Themes of the Moment. The Inevitability of War. Is jazz like math? Frozen yogurt flavors with what toppings? I wrote ...

A little over five years back, I had a message on my voice mail from one Al Mac-Teer-which I heard as Almick Tear-from a number in the 310 area code. This no-nonsense woman asked me to call her back regarding a thin little memoir I had written called A Stairway Down to Heaven about my years of tending bar in a small subterranean club that played live music way back in the '80s. At the time, I was also, sort of, a freelance journalist in and around Pittsburgh, PA. And I wrote movie reviews. These days I teach Creative Writing, Common Literature, and Film Studies at Mount Chisholm College of the Arts in the hills of Montana. Bozeman is a gorgeous if stark drive away. I get very few voice mails from Los Angeles, California.

"My boss read your memoir," Ms. Mac-Teer told me. "He says you write like he thinks."

"Your boss is brilliant," I told her, then asked, "Who is your boss?" When she told me she worked for Bill Johnson, that I had reached her on her cell as she was driving from her home in Santa Monica to her office in the Capitol Records Building in Hollywood for a meeting with him, I hollered, "You work for Bi-Bi-Bi-Bill JOHNSON? The movie director? Prove it."

Some days later, I was on the phone with Bi-Bi-Bi-Bill Johnson himself, and we were talking about his line of work, one of the subjects I teach. When I told him I'd seen his entire filmography, he accused me of blowing smoke. When I rattled off many salient points from his movies, he told me to shut up, enough already. At that time, he was "noodling" a screenplay about music in the transformative years of the '60s going into the '70s-when bands evolved from matching outfits and three-minute songs for AM radio to LP side-long jams and the Jimi Hendrix Experience. The stories from my book were full of very personal details. Even though my era was twenty years after what he was "noodling"-our club booked unheralded jazz combos and Depeche Mode cover bands-the stuff that happens in live-music venues is timeless, universal. The fights, the drugs, the serious love, the fun sex, the fun love, the serious sex, the laughs and the screaming, the Who-Gets-In and Who-Gets-Bounced-the whole riotous scene of procedures both spoken and intuitive-were the human behaviors that he wanted to nail. He offered me money for my book-the nonexclusive rights to my story, meaning I could still sell the exclusive rights, if there should ever be an offer. Fat chance. Still, I made more money selling him the rights to my book than I did selling copies of the thing.

Bill went off to film Pocket Rockets but kept up with me through calls and many typewritten letters-missives of wandering topics, his Themes of the Moment. The Inevitability of War. Is jazz like math? Frozen yogurt flavors with what toppings? I wrote ...

Readers Top Reviews

larryH. Yellen

Waste of time and my money. Read like a "B" movie. Thought I was going to get a book on how movies are made-did not get that. First section "Source Material" not necessary. Great disappointment.

MarijolarryH. Yel

I hope this is how movies are really made. If so, it is instructive. Beyond that, it is a good story with well developed, distinct characters (even if a few too many). Highly recommend it.

Kansas SunflowerM

Not knowing anything about making movies, this was a beginners' guide to the process. The characters in the book are well developed and fascinating to "meet". Lovely to know that one of my favorite actors is so multi-talented.

JiminylenaKansas

If Mr. Hanks ever wants to give up his day job, I believe he could have a career as a writer. But I hope he goes on doing both. This was a complicated and fascinating story, very vividly told. I enjoyed it very much.

richard e whitelo

Our granddaughter is in film school so this fictious, yet credible book written by Tom Hanks will serve as an imortant reference in her preparation tp fulfill her childhood dream of being a screen writer, director and producer. It always helps to have knowledhe of what made those who went before you successful. This book will serve as a Primer. It is also a very interesting book for any inquisite reader to enjoy. It talks about a profession we are all knowledgable of.

Short Excerpt Teaser

1 Backstory

A little over five years back, I had a message on my voice mail from one Al Mac-Teer-which I heard as Almick Tear-from a number in the 310 area code. This no-nonsense woman asked me to call her back regarding a thin little memoir I had written called A Stairway Down to Heaven about my years of tending bar in a small subterranean club that played live music way back in the '80s. At the time, I was also, sort of, a freelance journalist in and around Pittsburgh, PA. And I wrote movie reviews. These days I teach Creative Writing, Common Literature, and Film Studies at Mount Chisholm College of the Arts in the hills of Montana. Bozeman is a gorgeous if stark drive away. I get very few voice mails from Los Angeles, California.

"My boss read your memoir," Ms. Mac-Teer told me. "He says you write like he thinks."

"Your boss is brilliant," I told her, then asked, "Who is your boss?" When she told me she worked for Bill Johnson, that I had reached her on her cell as she was driving from her home in Santa Monica to her office in the Capitol Records Building in Hollywood for a meeting with him, I hollered, "You work for Bi-Bi-Bi-Bill JOHNSON? The movie director? Prove it."

Some days later, I was on the phone with Bi-Bi-Bi-Bill Johnson himself, and we were talking about his line of work, one of the subjects I teach. When I told him I'd seen his entire filmography, he accused me of blowing smoke. When I rattled off many salient points from his movies, he told me to shut up, enough already. At that time, he was "noodling" a screenplay about music in the transformative years of the '60s going into the '70s-when bands evolved from matching outfits and three-minute songs for AM radio to LP side-long jams and the Jimi Hendrix Experience. The stories from my book were full of very personal details. Even though my era was twenty years after what he was "noodling"-our club booked unheralded jazz combos and Depeche Mode cover bands-the stuff that happens in live-music venues is timeless, universal. The fights, the drugs, the serious love, the fun sex, the fun love, the serious sex, the laughs and the screaming, the Who-Gets-In and Who-Gets-Bounced-the whole riotous scene of procedures both spoken and intuitive-were the human behaviors that he wanted to nail. He offered me money for my book-the nonexclusive rights to my story, meaning I could still sell the exclusive rights, if there should ever be an offer. Fat chance. Still, I made more money selling him the rights to my book than I did selling copies of the thing.

Bill went off to film Pocket Rockets but kept up with me through calls and many typewritten letters-missives of wandering topics, his Themes of the Moment. The Inevitability of War. Is jazz like math? Frozen yogurt flavors with what toppings? I wrote him back in fountain pen-typewriters? honestly!-because I can match anyone in idiosyncrasy.

I received a single-page letter from him that had only this typed on it:

What films do you hate-walk out of ? Why?

Bill

I wrote him right back.

I don't hate any films. Movies are too hard to make to warrant hatred, even when they are turkeys. If a movie is not great, I just wait it out in my seat. It will be over soon enough. Walking out of a movie is a sin.

I'm guessing the US Postal Service needed two days to deliver my response, and a day was spent getting it to Bill's eyeballs, because three days later Al Mac-Teer called me. Her boss wanted me to "get down here, pronto" and watch him make a movie. The term break was coming up, I had never been to Atlanta, and a movie director was inviting me to see the making of a movie. I teach Film Studies but had never witnessed one being made. I flew to Salt Lake City for the connecting flight.

"You said something I have always thought," Bill said to me when I arrived on the set of Pocket Rockets, somewhere in the endless suburb that is greater Atlanta. "Sure, some movies don't work. Some fail in their intent. But anyone who says they hated a movie is treating a voluntarily shared human experience like a bad Red-Eye out of LAX. The departure is delayed for hours, there's turbulence that scares even the flight attendants, the guy across from you vomits, they can't serve any food and the booze runs out, you're seated next to twin babies with the colic, and you land too late for your meeting in the city. You can hate that. But hating a movie misses the damn point. Would you say you hated the seventh birthday party of your girlfriend's niece or a ball game that went eleven innings and ended 1–0? You hate cake and extra baseball for your money? Hate should be saved for fascism and steamed broccoli that's gone cold. The worst anyone-especially we who take Fountain-should ever say about someon...

A little over five years back, I had a message on my voice mail from one Al Mac-Teer-which I heard as Almick Tear-from a number in the 310 area code. This no-nonsense woman asked me to call her back regarding a thin little memoir I had written called A Stairway Down to Heaven about my years of tending bar in a small subterranean club that played live music way back in the '80s. At the time, I was also, sort of, a freelance journalist in and around Pittsburgh, PA. And I wrote movie reviews. These days I teach Creative Writing, Common Literature, and Film Studies at Mount Chisholm College of the Arts in the hills of Montana. Bozeman is a gorgeous if stark drive away. I get very few voice mails from Los Angeles, California.

"My boss read your memoir," Ms. Mac-Teer told me. "He says you write like he thinks."

"Your boss is brilliant," I told her, then asked, "Who is your boss?" When she told me she worked for Bill Johnson, that I had reached her on her cell as she was driving from her home in Santa Monica to her office in the Capitol Records Building in Hollywood for a meeting with him, I hollered, "You work for Bi-Bi-Bi-Bill JOHNSON? The movie director? Prove it."

Some days later, I was on the phone with Bi-Bi-Bi-Bill Johnson himself, and we were talking about his line of work, one of the subjects I teach. When I told him I'd seen his entire filmography, he accused me of blowing smoke. When I rattled off many salient points from his movies, he told me to shut up, enough already. At that time, he was "noodling" a screenplay about music in the transformative years of the '60s going into the '70s-when bands evolved from matching outfits and three-minute songs for AM radio to LP side-long jams and the Jimi Hendrix Experience. The stories from my book were full of very personal details. Even though my era was twenty years after what he was "noodling"-our club booked unheralded jazz combos and Depeche Mode cover bands-the stuff that happens in live-music venues is timeless, universal. The fights, the drugs, the serious love, the fun sex, the fun love, the serious sex, the laughs and the screaming, the Who-Gets-In and Who-Gets-Bounced-the whole riotous scene of procedures both spoken and intuitive-were the human behaviors that he wanted to nail. He offered me money for my book-the nonexclusive rights to my story, meaning I could still sell the exclusive rights, if there should ever be an offer. Fat chance. Still, I made more money selling him the rights to my book than I did selling copies of the thing.

Bill went off to film Pocket Rockets but kept up with me through calls and many typewritten letters-missives of wandering topics, his Themes of the Moment. The Inevitability of War. Is jazz like math? Frozen yogurt flavors with what toppings? I wrote him back in fountain pen-typewriters? honestly!-because I can match anyone in idiosyncrasy.

I received a single-page letter from him that had only this typed on it:

What films do you hate-walk out of ? Why?

Bill

I wrote him right back.

I don't hate any films. Movies are too hard to make to warrant hatred, even when they are turkeys. If a movie is not great, I just wait it out in my seat. It will be over soon enough. Walking out of a movie is a sin.

I'm guessing the US Postal Service needed two days to deliver my response, and a day was spent getting it to Bill's eyeballs, because three days later Al Mac-Teer called me. Her boss wanted me to "get down here, pronto" and watch him make a movie. The term break was coming up, I had never been to Atlanta, and a movie director was inviting me to see the making of a movie. I teach Film Studies but had never witnessed one being made. I flew to Salt Lake City for the connecting flight.

"You said something I have always thought," Bill said to me when I arrived on the set of Pocket Rockets, somewhere in the endless suburb that is greater Atlanta. "Sure, some movies don't work. Some fail in their intent. But anyone who says they hated a movie is treating a voluntarily shared human experience like a bad Red-Eye out of LAX. The departure is delayed for hours, there's turbulence that scares even the flight attendants, the guy across from you vomits, they can't serve any food and the booze runs out, you're seated next to twin babies with the colic, and you land too late for your meeting in the city. You can hate that. But hating a movie misses the damn point. Would you say you hated the seventh birthday party of your girlfriend's niece or a ball game that went eleven innings and ended 1–0? You hate cake and extra baseball for your money? Hate should be saved for fascism and steamed broccoli that's gone cold. The worst anyone-especially we who take Fountain-should ever say about someon...