Science & Math

Nature & Ecology

- Publisher : Milkweed Editions

- Published : 15 Aug 2023

- Pages : 424

- ISBN-10 : 1571313966

- ISBN-13 : 9781571313966

- Language : English

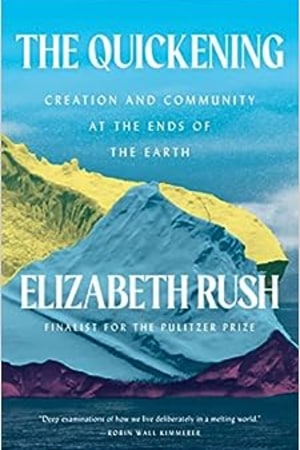

The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth

An August 2023 Indie Next Pick, selected by booksellers

A Vogue Most Anticipated Book of 2023

A WBUR Summer Reading Recommendation

A Next Big Idea Club's August 2023 Must-Read Book

An astonishing, vital book about Antarctica, climate change, and motherhood from the author of Rising, finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in General Nonfiction.

In 2019, fifty-seven scientists and crew set out onboard the Nathaniel B. Palmer. Their destination: Thwaites Glacier. Their goal: to learn as much as possible about this mysterious place, never before visited by humans, and believed to be both rapidly deteriorating and capable of making a catastrophic impact on global sea-level rise.

In The Quickening, Elizabeth Rush documents their voyage, offering the sublime-seeing an iceberg for the first time; the staggering waves of the Drake Passage; the torqued, unfamiliar contours of Thwaites-alongside the workaday moments of this groundbreaking expedition. A ping-pong tournament at sea. Long hours in the lab. All the effort that goes into caring for and protecting human life in a place that is inhospitable to it. Along the way, she takes readers on a personal journey around a more intimate question: What does it mean to bring a child into the world at this time of radical change?

What emerges is a new kind of Antarctica story, one preoccupied not with flag planting but with the collective and challenging work of imagining a better future. With understanding the language of a continent where humans have only been present for two centuries. With the contributions and concerns of women, who were largely excluded from voyages until the last few decades, and of crew members of color, whose labor has often gone unrecognized.The Quickening teems with their voices-with the colorful stories and personalities of Rush's shipmates-in a thrilling chorus.

Urgent and brave, absorbing and vulnerable, The Quickeningis another essential book from Elizabeth Rush.

A Vogue Most Anticipated Book of 2023

A WBUR Summer Reading Recommendation

A Next Big Idea Club's August 2023 Must-Read Book

An astonishing, vital book about Antarctica, climate change, and motherhood from the author of Rising, finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in General Nonfiction.

In 2019, fifty-seven scientists and crew set out onboard the Nathaniel B. Palmer. Their destination: Thwaites Glacier. Their goal: to learn as much as possible about this mysterious place, never before visited by humans, and believed to be both rapidly deteriorating and capable of making a catastrophic impact on global sea-level rise.

In The Quickening, Elizabeth Rush documents their voyage, offering the sublime-seeing an iceberg for the first time; the staggering waves of the Drake Passage; the torqued, unfamiliar contours of Thwaites-alongside the workaday moments of this groundbreaking expedition. A ping-pong tournament at sea. Long hours in the lab. All the effort that goes into caring for and protecting human life in a place that is inhospitable to it. Along the way, she takes readers on a personal journey around a more intimate question: What does it mean to bring a child into the world at this time of radical change?

What emerges is a new kind of Antarctica story, one preoccupied not with flag planting but with the collective and challenging work of imagining a better future. With understanding the language of a continent where humans have only been present for two centuries. With the contributions and concerns of women, who were largely excluded from voyages until the last few decades, and of crew members of color, whose labor has often gone unrecognized.The Quickening teems with their voices-with the colorful stories and personalities of Rush's shipmates-in a thrilling chorus.

Urgent and brave, absorbing and vulnerable, The Quickeningis another essential book from Elizabeth Rush.

Editorial Reviews

Praise for The Quickening

"Elizabeth Rush's The Quickening is one part memoir, one part reporting from the edge-think Elizabeth Kolbert's The Sixth Extinction-a book that feels as though it was written from the brink. In this case the extreme scenario is literal: Rush, a journalist, joins a crew of scientists aboard a ship headed for a glacier in Antarctica that is, like much of the poles, rapidly disappearing. The book brings the environmental crisis into a personal sphere, asking what it means to have a child in the face of such catastrophic change. [. . .] Rush writes with clarity and precision, giving a visceral sense of everything from the gear required to traverse an arctic landscape to the interior landscape of a woman facing change both global and immediate."-Vogue, "Most Anticipated Books of 2023"

"In The Quickening, Elizabeth Rush takes readers to the precipice of the climate crisis. Aboard the Nathaniel B. Palmer, an American icebreaker, Rush and a crew of scientists, journalists, and support staff set bow and stern in front of Thwaites Glacier for the first time in history [. . .] The Quickening is a poignant, necessary addition to the body of Antarctic literature, one that centers-without glorifying-motherhood, uncertainty, community, vulnerability, and beauty in a rapidly melting world."-Science

"Elizabeth Rush takes readers along as she documents the 2019 Thwaites Glacier expedition in Antarctica. The voyage had 57 scientists, researchers and recorders onboard to document the groundbreaking glacier, which has never been visited by humans. [. . .] Rush ties her findings of the Thwaites Glacier expedition to raising kids and living in a quickly changing world."-WBUR, "8 Books to Add to Your Summer Reading List"

"The fascinating inside story of climate science at the edge of Antarctica [. . .] In this follow-up to Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, Rush shows us how data collection happens, capturing the intriguing details of climate science in the field [. . .] The scientists are not the only heroes of Rush's book, which emphasizes above all the collaborative and interdependent nature of such voyages, where so much depends on the ...

"Elizabeth Rush's The Quickening is one part memoir, one part reporting from the edge-think Elizabeth Kolbert's The Sixth Extinction-a book that feels as though it was written from the brink. In this case the extreme scenario is literal: Rush, a journalist, joins a crew of scientists aboard a ship headed for a glacier in Antarctica that is, like much of the poles, rapidly disappearing. The book brings the environmental crisis into a personal sphere, asking what it means to have a child in the face of such catastrophic change. [. . .] Rush writes with clarity and precision, giving a visceral sense of everything from the gear required to traverse an arctic landscape to the interior landscape of a woman facing change both global and immediate."-Vogue, "Most Anticipated Books of 2023"

"In The Quickening, Elizabeth Rush takes readers to the precipice of the climate crisis. Aboard the Nathaniel B. Palmer, an American icebreaker, Rush and a crew of scientists, journalists, and support staff set bow and stern in front of Thwaites Glacier for the first time in history [. . .] The Quickening is a poignant, necessary addition to the body of Antarctic literature, one that centers-without glorifying-motherhood, uncertainty, community, vulnerability, and beauty in a rapidly melting world."-Science

"Elizabeth Rush takes readers along as she documents the 2019 Thwaites Glacier expedition in Antarctica. The voyage had 57 scientists, researchers and recorders onboard to document the groundbreaking glacier, which has never been visited by humans. [. . .] Rush ties her findings of the Thwaites Glacier expedition to raising kids and living in a quickly changing world."-WBUR, "8 Books to Add to Your Summer Reading List"

"The fascinating inside story of climate science at the edge of Antarctica [. . .] In this follow-up to Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, Rush shows us how data collection happens, capturing the intriguing details of climate science in the field [. . .] The scientists are not the only heroes of Rush's book, which emphasizes above all the collaborative and interdependent nature of such voyages, where so much depends on the ...

Short Excerpt Teaser

Who knows when this all got started? When we became so tangled up in each other, in ice, in obsessing with endings already in motion and what it means to make a little life while the junk drawers overflow, and the jellyfish heap up on the shore, and the pollinator plants just keep blooming, even deep into October, long after the monarchs ought to be gone? What do we make of all that? What do we make amid all that? Each of us begins in our own way. And yet each of us begins the same.

The year I go to Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica is also the year I decide to try to grow a human being inside of my body. It is the year of becoming two: me and you. The year we all get onto that boat, my shipmates and I, the year we sail past 73° south to the untouched edge of Thwaites, is also just another year in which the ice lets go, a little more this time. Let's agree to call it a year––like the Year of Magical Thinking or the Year of Living Dangerously––though let's also agree that it may not coincide with anything that resembles a year on the calendar. It will not start and stop on a certain day, and there will not be 365 of anything. Instead time will flow sideways, the way floodwaters cover the lowest land first, and it will unspool quick as a metal cable lowering a scientific instrument down to the very bottom of the Amundsen Sea.

On our last night on solid earth, many of us sleep in a hotel called Dreams. Everything we do anticipates what we will soon be without. Some call the children they are leaving behind. Some call credit card companies, to set up automatic payments. And some head to the Colonial for a couple of drinks. One person runs along Route 9 to stretch her legs, while another runs to the market to purchase deodorant and a couple empanadas. I go to the steam room just above the hotel's casino. Then I go to the bar around the corner for my last pint, where I eye every person who enters, wondering if we will sail to Antarctica together. In the morning, I drink a glass of honeydew juice, followed by a glass of raspberry juice. I'm thinking: When am I going to drink fresh juice again? And, more importantly: Is this my last chance to be alone?

From my table at the breakfast buffet, I can see the Nathaniel B. Palmer tied to the pier. The research vessel looks like a winter slipper with the heel facing forward. The low stern flares into a wide bow with a relatively flat rake, so the boat can ride up on top of the sea ice we will soon encounter, forcing it to break. The Palmer's hull appears as orange as the inside of a papaya, its superstructure egg-yolk yellow. The Ice Tower, a boxy room with windows on all sides, sits at the very top, a kind of crow's nest for cold weather. Just beneath it: the bridge, where the officer on watch will oversee ship operations every single minute of every single day for the next nine weeks or more. Later, I will stand in that room and ask Captain Brandon how much the Palmer weighs and he will tell me 10,752,000 pounds. Yet I wouldn't call the ship large. It's roughly the length of a football field, a distance most humans can cross in under a minute without breaking a sweat. I squint through the hotel's smudged window, sip my second cup of coffee, and realize that I know nothing about whatever it is that I've gotten myself into.

Nine months earlier, I received a cryptic missive from Valentine Kass, my program officer at the National Science Foundation (NSF). It read: An interesting opportunity has come up. Call me in the morning. A strong wind blew all night, stripping the cherry blossoms from the trees. Valentine didn't wait for my response; instead she rang first thing to tell me that she had spent the previous day in a planning meeting for a five-year program to study Antarctica's most important and least understood glacier, Thwaites.

"This year they're deploying an icebreaker to investigate. There's one berth remaining, and I recommended it be given to you," Valentine said. Then she asked what was the longest I'd ever been on a boat.

"Five days," I told her, confident.

"Do you think you're up for sixty?"

"Sure," I said, perhaps a little too quickly.

"Where you'd be going, it's incredibly isolated." Valentine paused, as if waiting for me to signal comprehen...

The year I go to Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica is also the year I decide to try to grow a human being inside of my body. It is the year of becoming two: me and you. The year we all get onto that boat, my shipmates and I, the year we sail past 73° south to the untouched edge of Thwaites, is also just another year in which the ice lets go, a little more this time. Let's agree to call it a year––like the Year of Magical Thinking or the Year of Living Dangerously––though let's also agree that it may not coincide with anything that resembles a year on the calendar. It will not start and stop on a certain day, and there will not be 365 of anything. Instead time will flow sideways, the way floodwaters cover the lowest land first, and it will unspool quick as a metal cable lowering a scientific instrument down to the very bottom of the Amundsen Sea.

On our last night on solid earth, many of us sleep in a hotel called Dreams. Everything we do anticipates what we will soon be without. Some call the children they are leaving behind. Some call credit card companies, to set up automatic payments. And some head to the Colonial for a couple of drinks. One person runs along Route 9 to stretch her legs, while another runs to the market to purchase deodorant and a couple empanadas. I go to the steam room just above the hotel's casino. Then I go to the bar around the corner for my last pint, where I eye every person who enters, wondering if we will sail to Antarctica together. In the morning, I drink a glass of honeydew juice, followed by a glass of raspberry juice. I'm thinking: When am I going to drink fresh juice again? And, more importantly: Is this my last chance to be alone?

From my table at the breakfast buffet, I can see the Nathaniel B. Palmer tied to the pier. The research vessel looks like a winter slipper with the heel facing forward. The low stern flares into a wide bow with a relatively flat rake, so the boat can ride up on top of the sea ice we will soon encounter, forcing it to break. The Palmer's hull appears as orange as the inside of a papaya, its superstructure egg-yolk yellow. The Ice Tower, a boxy room with windows on all sides, sits at the very top, a kind of crow's nest for cold weather. Just beneath it: the bridge, where the officer on watch will oversee ship operations every single minute of every single day for the next nine weeks or more. Later, I will stand in that room and ask Captain Brandon how much the Palmer weighs and he will tell me 10,752,000 pounds. Yet I wouldn't call the ship large. It's roughly the length of a football field, a distance most humans can cross in under a minute without breaking a sweat. I squint through the hotel's smudged window, sip my second cup of coffee, and realize that I know nothing about whatever it is that I've gotten myself into.

Nine months earlier, I received a cryptic missive from Valentine Kass, my program officer at the National Science Foundation (NSF). It read: An interesting opportunity has come up. Call me in the morning. A strong wind blew all night, stripping the cherry blossoms from the trees. Valentine didn't wait for my response; instead she rang first thing to tell me that she had spent the previous day in a planning meeting for a five-year program to study Antarctica's most important and least understood glacier, Thwaites.

"This year they're deploying an icebreaker to investigate. There's one berth remaining, and I recommended it be given to you," Valentine said. Then she asked what was the longest I'd ever been on a boat.

"Five days," I told her, confident.

"Do you think you're up for sixty?"

"Sure," I said, perhaps a little too quickly.

"Where you'd be going, it's incredibly isolated." Valentine paused, as if waiting for me to signal comprehen...