- Publisher : Soho Press

- Published : 13 Jun 2023

- Pages : 336

- ISBN-10 : 1641294841

- ISBN-13 : 9781641294843

- Language : English

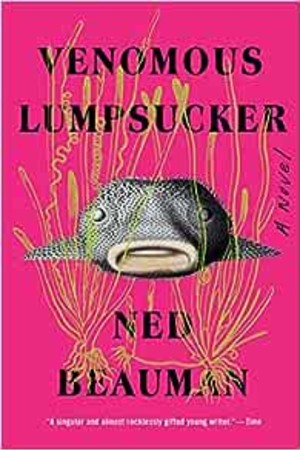

Venomous Lumpsucker

A dark and witty story of environmental collapse and runaway capitalism from the Booker-listed author of The Teleportation Accident.

The near future. Tens of thousands of species are going extinct every year. And a whole industry has sprung up around their extinctions, to help us preserve the remnants, or perhaps just assuage our guilt. For instance, the biobanks: secure archives of DNA samples, from which lost organisms might someday be resurrected . . . But then, one day, it's all gone. A mysterious cyber-attack hits every biobank simultaneously, wiping out the last traces of the perished species. Now we're never getting them back.

Karin Resaint and Mark Halyard are concerned with one species in particular: the venomous lumpsucker, a small, ugly bottom-feeder that happens to be the most intelligent fish on the planet. Resaint is an animal cognition scientist consumed with existential grief over what humans have done to nature. Halyard is an exec from the extinction industry, complicit in the mining operation that destroyed the lumpsucker's last-known habitat.

Across the dystopian landscapes of the 2030s-a nature reserve full of toxic waste; a floating city on the ocean; the hinterlands of a totalitarian state-Resaint and Halyard hunt for a surviving lumpsucker. And the further they go, the deeper they're drawn into the mystery of the attack on the biobanks. Who was really behind it? And why would anyone do such a thing?

Virtuosic and profound, witty and despairing, Venomous Lumpsucker is Ned Beauman at his very best.

The near future. Tens of thousands of species are going extinct every year. And a whole industry has sprung up around their extinctions, to help us preserve the remnants, or perhaps just assuage our guilt. For instance, the biobanks: secure archives of DNA samples, from which lost organisms might someday be resurrected . . . But then, one day, it's all gone. A mysterious cyber-attack hits every biobank simultaneously, wiping out the last traces of the perished species. Now we're never getting them back.

Karin Resaint and Mark Halyard are concerned with one species in particular: the venomous lumpsucker, a small, ugly bottom-feeder that happens to be the most intelligent fish on the planet. Resaint is an animal cognition scientist consumed with existential grief over what humans have done to nature. Halyard is an exec from the extinction industry, complicit in the mining operation that destroyed the lumpsucker's last-known habitat.

Across the dystopian landscapes of the 2030s-a nature reserve full of toxic waste; a floating city on the ocean; the hinterlands of a totalitarian state-Resaint and Halyard hunt for a surviving lumpsucker. And the further they go, the deeper they're drawn into the mystery of the attack on the biobanks. Who was really behind it? And why would anyone do such a thing?

Virtuosic and profound, witty and despairing, Venomous Lumpsucker is Ned Beauman at his very best.

Editorial Reviews

CHAPTER ONE

At a primate research institute in Leipzig, a scientist was caught disabling the surveillance cameras inside the enclosure of an orangutan who knew two thousand words of sign language. He had with him a container of prunes, the orangutan's favorite snack, and upon these prunes suspicion soon fell; perhaps the scientist let something slip under questioning, or perhaps he was seen casting nervous glances at the container. So the prunes were examined, and a pill was found hidden in one of them. Tests revealed that the pill was a 4mg dose of the memory-suppressing drug bamaluzole.

In other words, he was planning to roofie the orangutan.

After the story got out, nearly everyone assumed that the scientist's intentions were sexual, and this became gag material for comedians all over the world. But Karin Resaint, who had once seen this scientist taking part in a panel on animal cognition-who remembered a remark he had made about "unspeakable loss"-understood at once that the scientist didn't want to have sex with the orangutan. He wanted something far more extreme.

SHE WAS READY to put the last of the fish into the air when Abdi came running out on deck to warn her. He pointed north into the dusk. Some time ago, Resaint had noticed on the horizon what she had taken for an isolated storm cloud, the mist tightening as night fell into a knot of heavier weather. But now that it had drawn closer, and she looked again, she could make out the three tall columns at the base of the cloud, like chimneys venting the surge out of the sea. A spindrifter, sailing in this direction. The first she'd seen in all her time on the Baltic.

Her cargo drone was supposed to fly due north. That would take it right into the spindrifter's path, she realized, and it would be lashed out of the air. The storm around a spindrifter was like no storm in nature. It was prodigious not in strength but in geometry. Guillemots and herring gulls, which were unfazed by the most furious winter tempests, got tossed around like waste paper. It was too alien to their wings. And this drone, which most of the time did okay in high winds, wouldn't even know what hit it.

She still had the drone's flight path up on the screen of her phone, so she turned on the overlay that showed other nearby vessels. Abdi pointed out the spindrifter, which on the map was just an anonymous white dot. She bent the flight path so the drone would keep a nice safe distance off to the east.

"Thanks," she said, touching him on the arm. She looked again at the spindrifter's course on the map. "It sort of looks like it's heading straight fo...

At a primate research institute in Leipzig, a scientist was caught disabling the surveillance cameras inside the enclosure of an orangutan who knew two thousand words of sign language. He had with him a container of prunes, the orangutan's favorite snack, and upon these prunes suspicion soon fell; perhaps the scientist let something slip under questioning, or perhaps he was seen casting nervous glances at the container. So the prunes were examined, and a pill was found hidden in one of them. Tests revealed that the pill was a 4mg dose of the memory-suppressing drug bamaluzole.

In other words, he was planning to roofie the orangutan.

After the story got out, nearly everyone assumed that the scientist's intentions were sexual, and this became gag material for comedians all over the world. But Karin Resaint, who had once seen this scientist taking part in a panel on animal cognition-who remembered a remark he had made about "unspeakable loss"-understood at once that the scientist didn't want to have sex with the orangutan. He wanted something far more extreme.

SHE WAS READY to put the last of the fish into the air when Abdi came running out on deck to warn her. He pointed north into the dusk. Some time ago, Resaint had noticed on the horizon what she had taken for an isolated storm cloud, the mist tightening as night fell into a knot of heavier weather. But now that it had drawn closer, and she looked again, she could make out the three tall columns at the base of the cloud, like chimneys venting the surge out of the sea. A spindrifter, sailing in this direction. The first she'd seen in all her time on the Baltic.

Her cargo drone was supposed to fly due north. That would take it right into the spindrifter's path, she realized, and it would be lashed out of the air. The storm around a spindrifter was like no storm in nature. It was prodigious not in strength but in geometry. Guillemots and herring gulls, which were unfazed by the most furious winter tempests, got tossed around like waste paper. It was too alien to their wings. And this drone, which most of the time did okay in high winds, wouldn't even know what hit it.

She still had the drone's flight path up on the screen of her phone, so she turned on the overlay that showed other nearby vessels. Abdi pointed out the spindrifter, which on the map was just an anonymous white dot. She bent the flight path so the drone would keep a nice safe distance off to the east.

"Thanks," she said, touching him on the arm. She looked again at the spindrifter's course on the map. "It sort of looks like it's heading straight fo...

Readers Top Reviews

Graham GodfreyKindle

Don’t take this book too seriously, just enjoy it It’s well written and an interesting and well developed plot, but it is meant as a series of interesting and thought provoking ideas rather than a heavyweight “aren’t humans terrible” of the Attenborough persuasion

alexw

A bit like the early Neal Stephenson, before he got lost in Baroque. Thoroughly enjoyed it.

BillieArt Shapiro

Venomous Lumpsucker by Ned Beauman Science Fiction Dystopia Audio In the future, just about every living animal, plant, and insect are extinct but saved as DNA samples so that 'maybe' 'one day' they could be brought back to life. So now, after paying for extinction credits to make sure samples are banked, companies can wipe out the last of any species. But a cyber hack destroys all those places the samples were saved, and now they are lost forever. Though, other than the stock prices going up on the extinction credits, nobody really cares. Karin and Mark are two who do. Karin because she's trying to save a fish, the venomous lumpsucker, and Mark because he sold some of his company's credit hoping to make a quick buck under the table. When I started this book, I was hoping for a dark comedy, as the blurb hinted at... Eh. There were some funnies, but not enough. And it wasn't dark. It was boring. Very disappointing. A lot of the dialogue switched into a telling; (“I went to this school,” she said, then told them about how her date stood her up. The dress she had bought was dark brown...”). Maybe, if the story had been centered on the science fiction aspect, instead of the daily lives of the characters, and a little bit of action as they travel here and there to find the fish, the story might have worked better, but as is, it read more like a fictionalized memoir than a science fiction novel. And the ending... Lame and not that surprising. 1 Star

NAdorabrooke

The argument that the “Nazis we bad, but they create an environmental code, so the 40 million people dead in ww2 is forgiven”.

Chris Bish

Ned Beauman’s imagination is at the cosmic level. His depiction of our corrupt society is perfect. Not even the real threat of extinction to humans changes the greed index. Beauman’s description of our world as it nears the end of humans is compelling, real and amazingly, funny.

Short Excerpt Teaser

CHAPTER ONE

At a primate research institute in Leipzig, a scientist was caught disabling the surveillance cameras inside the enclosure of an orangutan who knew two thousand words of sign language. He had with him a container of prunes, the orangutan's favorite snack, and upon these prunes suspicion soon fell; perhaps the scientist let something slip under questioning, or perhaps he was seen casting nervous glances at the container. So the prunes were examined, and a pill was found hidden in one of them. Tests revealed that the pill was a 4mg dose of the memory-suppressing drug bamaluzole.

In other words, he was planning to roofie the orangutan.

After the story got out, nearly everyone assumed that the scientist's intentions were sexual, and this became gag material for comedians all over the world. But Karin Resaint, who had once seen this scientist taking part in a panel on animal cognition-who remembered a remark he had made about "unspeakable loss"-understood at once that the scientist didn't want to have sex with the orangutan. He wanted something far more extreme.

SHE WAS READY to put the last of the fish into the air when Abdi came running out on deck to warn her. He pointed north into the dusk. Some time ago, Resaint had noticed on the horizon what she had taken for an isolated storm cloud, the mist tightening as night fell into a knot of heavier weather. But now that it had drawn closer, and she looked again, she could make out the three tall columns at the base of the cloud, like chimneys venting the surge out of the sea. A spindrifter, sailing in this direction. The first she'd seen in all her time on the Baltic.

Her cargo drone was supposed to fly due north. That would take it right into the spindrifter's path, she realized, and it would be lashed out of the air. The storm around a spindrifter was like no storm in nature. It was prodigious not in strength but in geometry. Guillemots and herring gulls, which were unfazed by the most furious winter tempests, got tossed around like waste paper. It was too alien to their wings. And this drone, which most of the time did okay in high winds, wouldn't even know what hit it.

She still had the drone's flight path up on the screen of her phone, so she turned on the overlay that showed other nearby vessels. Abdi pointed out the spindrifter, which on the map was just an anonymous white dot. She bent the flight path so the drone would keep a nice safe distance off to the east.

"Thanks," she said, touching him on the arm. She looked again at the spindrifter's course on the map. "It sort of looks like it's heading straight for us?"

"It won't hit us," Abdi said. "But also it won't care about getting really close. You want to be inside for that, definitely."

In any case, Resaint thought, the Varuna was almost the size of an aircraft carrier, so the spindrifter would probably come off worse in a collision. Which was a pity, in some ways, because she enjoyed the thought of the Varuna getting rent open. Not while she was on board, maybe, but nevertheless this was a ship that deserved to be sunk. That would be a much more productive use of the spindrifter's evening than dazing a few seabirds.

She murmured to her phone, and the drone's rotors began to whirr. It lifted from the deck, trailing four lengths of cable from its underside, until the cables tautened and its cargo heaved up too: a plastic tank that held ten venomous lumpsuckers swimming around in sixty gallons of seawater. The drone continued to rise until the tank was high enough to clear the railing around the deck, and Resaint felt a sacramental sprinkling on her forehead as water slopped out over the side. Then, accelerating gently, like a stork with an especially precious baby in its sling, the drone set off north over the ocean.

The drone would fly about twenty kilometers to the South Kvarken reefs where venomous lumpsuckers gathered every breeding season, and then dump out the contents of the tank. In theory, after finishing her experiments, Resaint could have just lowered the fish over the side of the Varuna and let them find their own way home. They were perfectly capable navigators. But she refused to take the risk. There were so few left. Every one was so precious. Which is why it would have been a particularly shameful mishap if, say, the spindrifter had clobbered the...

At a primate research institute in Leipzig, a scientist was caught disabling the surveillance cameras inside the enclosure of an orangutan who knew two thousand words of sign language. He had with him a container of prunes, the orangutan's favorite snack, and upon these prunes suspicion soon fell; perhaps the scientist let something slip under questioning, or perhaps he was seen casting nervous glances at the container. So the prunes were examined, and a pill was found hidden in one of them. Tests revealed that the pill was a 4mg dose of the memory-suppressing drug bamaluzole.

In other words, he was planning to roofie the orangutan.

After the story got out, nearly everyone assumed that the scientist's intentions were sexual, and this became gag material for comedians all over the world. But Karin Resaint, who had once seen this scientist taking part in a panel on animal cognition-who remembered a remark he had made about "unspeakable loss"-understood at once that the scientist didn't want to have sex with the orangutan. He wanted something far more extreme.

SHE WAS READY to put the last of the fish into the air when Abdi came running out on deck to warn her. He pointed north into the dusk. Some time ago, Resaint had noticed on the horizon what she had taken for an isolated storm cloud, the mist tightening as night fell into a knot of heavier weather. But now that it had drawn closer, and she looked again, she could make out the three tall columns at the base of the cloud, like chimneys venting the surge out of the sea. A spindrifter, sailing in this direction. The first she'd seen in all her time on the Baltic.

Her cargo drone was supposed to fly due north. That would take it right into the spindrifter's path, she realized, and it would be lashed out of the air. The storm around a spindrifter was like no storm in nature. It was prodigious not in strength but in geometry. Guillemots and herring gulls, which were unfazed by the most furious winter tempests, got tossed around like waste paper. It was too alien to their wings. And this drone, which most of the time did okay in high winds, wouldn't even know what hit it.

She still had the drone's flight path up on the screen of her phone, so she turned on the overlay that showed other nearby vessels. Abdi pointed out the spindrifter, which on the map was just an anonymous white dot. She bent the flight path so the drone would keep a nice safe distance off to the east.

"Thanks," she said, touching him on the arm. She looked again at the spindrifter's course on the map. "It sort of looks like it's heading straight for us?"

"It won't hit us," Abdi said. "But also it won't care about getting really close. You want to be inside for that, definitely."

In any case, Resaint thought, the Varuna was almost the size of an aircraft carrier, so the spindrifter would probably come off worse in a collision. Which was a pity, in some ways, because she enjoyed the thought of the Varuna getting rent open. Not while she was on board, maybe, but nevertheless this was a ship that deserved to be sunk. That would be a much more productive use of the spindrifter's evening than dazing a few seabirds.

She murmured to her phone, and the drone's rotors began to whirr. It lifted from the deck, trailing four lengths of cable from its underside, until the cables tautened and its cargo heaved up too: a plastic tank that held ten venomous lumpsuckers swimming around in sixty gallons of seawater. The drone continued to rise until the tank was high enough to clear the railing around the deck, and Resaint felt a sacramental sprinkling on her forehead as water slopped out over the side. Then, accelerating gently, like a stork with an especially precious baby in its sling, the drone set off north over the ocean.

The drone would fly about twenty kilometers to the South Kvarken reefs where venomous lumpsuckers gathered every breeding season, and then dump out the contents of the tank. In theory, after finishing her experiments, Resaint could have just lowered the fish over the side of the Varuna and let them find their own way home. They were perfectly capable navigators. But she refused to take the risk. There were so few left. Every one was so precious. Which is why it would have been a particularly shameful mishap if, say, the spindrifter had clobbered the...