Politics & Government

- Publisher : Random House Trade Paperbacks; Reprint edition

- Published : 24 May 2022

- Pages : 384

- ISBN-10 : 1984856073

- ISBN-13 : 9781984856074

- Language : English

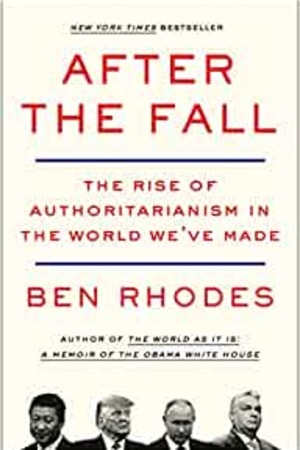

After the Fall: The Rise of Authoritarianism in the World We've Made

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • "Vital reading for Americans and people anywhere who seek to understand what is happening ‘after the fall' of the global system created by the United States" (New York Journal of Books), from the former White House aide, close confidant to President Barack Obama, and author of The World as It Is

At a time when democracy in the United States is endangered as never before, Ben Rhodes spent years traveling the world to understand why. He visited dozens of countries, meeting with politicians and activists confronting the same nationalism and authoritarianism that are tearing America apart. Along the way, he discusses the growing authoritarianism of Vladimir Putin, and his aggression towards Ukraine, with the foremost opposition leader in Russia, who was subsequently poisoned and imprisoned; he profiled Hong Kong protesters who saw their movement snuffed out by China under Xi Jinping; and America itself reached the precipice of losing democracy before giving itself a fragile second chance.

The characters and issues that Rhodes illuminates paint a picture that shows us where we are today-from Barack Obama to a rising generation of international leaders; from the authoritarian playbook endangering democracy to the flood of disinformation enabling authoritarianism. Ultimately, Rhodes writes personally and powerfully about finding hope in the belief that looking squarely at where America has gone wrong can make clear how essential it is to fight for what America is supposed to be, for our own country and the entire world.

At a time when democracy in the United States is endangered as never before, Ben Rhodes spent years traveling the world to understand why. He visited dozens of countries, meeting with politicians and activists confronting the same nationalism and authoritarianism that are tearing America apart. Along the way, he discusses the growing authoritarianism of Vladimir Putin, and his aggression towards Ukraine, with the foremost opposition leader in Russia, who was subsequently poisoned and imprisoned; he profiled Hong Kong protesters who saw their movement snuffed out by China under Xi Jinping; and America itself reached the precipice of losing democracy before giving itself a fragile second chance.

The characters and issues that Rhodes illuminates paint a picture that shows us where we are today-from Barack Obama to a rising generation of international leaders; from the authoritarian playbook endangering democracy to the flood of disinformation enabling authoritarianism. Ultimately, Rhodes writes personally and powerfully about finding hope in the belief that looking squarely at where America has gone wrong can make clear how essential it is to fight for what America is supposed to be, for our own country and the entire world.

Editorial Reviews

Praise for The World as It Is

"A classic coming-of-age story, about the journey from idealism to realism, told with candor and immediacy . . . [Ben Rhodes's] achievement is rare for a political memoir: He has written a humane and honorable book."-The New York Times Book Review

"More than any other White House memoirist, Rhodes is a creature of the man he served."-The New Yorker

"Insightful, funny, and moving, this is a beautifully observed, essential record of what it was like to be there."-Samantha Power

"A classic coming-of-age story, about the journey from idealism to realism, told with candor and immediacy . . . [Ben Rhodes's] achievement is rare for a political memoir: He has written a humane and honorable book."-The New York Times Book Review

"More than any other White House memoirist, Rhodes is a creature of the man he served."-The New Yorker

"Insightful, funny, and moving, this is a beautifully observed, essential record of what it was like to be there."-Samantha Power

Readers Top Reviews

PattyFirebrain Fi

I thought this book was extraordinary. Rhodes is a beautiful writer who takes us on a clear eyed journey around the world. The book left me feeling hopeful and I’m better for reading it.

Steven KelberJohn

Ben Rhodes' retrospective on history demonstrates the power of the saying there are none so blind as those who will not see 7 different times he asserts that America had achieved world hegemony then lost it through a financial crisis of its own making in 2008. Never mind the lack of support for that position - YOU WERE IN POWER THEN! In eight years what did you do to make things better. Tortured analogies of mismatched countries and leaders is a poor substitute for rational discussion and makes for an empirically flawed and uninteresting text

Laura P.Steven Ke

I inhaled this book as soon as it arrived, and it did not disappoint. I generally dislike political analysis, but this book has so much more. We learn through story, and this is above all else a fascinating story.

ElayneLaura P.Ste

Super insightful! I loved the perspective this book gave me on the rise of nationalism across the world. Rhode's writing is beautiful. The book left me feeling hopeful and informed about the current state of affairs and how we can improve. Highly recommend!

Rashid N KapadiaE

Ben Rhodes is a superb writer. It is hard to put this book down. He has unique perspective, access and determination. He transports us to an inner world which may well decide the fate of democracy. His selection of protagonists (all citizen warriors) is remarkable. For me, this book beautifully stitches together multiple fears, stories, and threads into a comprehensive whole. One book which gives you a complete picture of what's at stake and what lies ahead. This is compulsory reading for anyone who is involved in or interested in the global political war between democracy & dictatorship.

Short Excerpt Teaser

7

The House of Soviets

For much of the twenty-first century, Russia has led the counterrevolution to American domination-not by seeking to upend the global order that America constructed, but rather by disrupting it from within, turning it (and ultimately America itself) into the ugliest version of itself. I think of how Russians must have seen us Americans as I was growing up: capitalist stooges, driven entirely by a lust for profit; a militarized empire, unconcerned with the lives of the distant people harmed by our foreign policies; racist hypocrites, preaching human rights abroad and practicing systemic oppression at home. That's the America that Putin wants the world to see, and that's the America that Putin wants us to be.

Think about it. Isn't that what you would want for someone that humiliated you? For them to be revealed, before the world, as the worst version of themselves? By doing so, Putin leveled the playing field-the world is what it is, a hard place in which might makes right, capitalism is as fungible as Communism, and a ruthless Russia will always have to be treated with the respect that it was denied after the wall came crashing down.

The city of Kaliningrad is one of those oddities of history, traded back and forth between empires and nation-states, swapping languages and ethnic majorities, caught in the shifting currents of history. Nestled between Poland and Lithuania along the Baltic Sea, it used to be the German city of Königsberg even though it didn't border Germany. After its brutal conquest by the Red Army, the city was renamed, Stalin repopulated it with Russians, and Kaliningrad served as the home for the Soviet Baltic fleet during the Cold War (as well as the home for some unverifiable number of nuclear weapons). After the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the Russians hung on to Kaliningrad even as neighboring Lithuania became free, leaving the city once again cut off from its nation-a part of Russia, two hundred miles from the Russian border. It was this peculiar political identity that drew me there in the summer of 2001-a twenty-three-year-old part-time teacher and graduate student with little idea what I was going to do with the rest of my life.

Before I got to Kaliningrad, I set foot on Russian soil for the first time, traveling through St. Petersburg and then the three Baltic nations, independent states for just a decade. St. Petersburg-Putin's hometown-seemed to be covered in a layer of dust. The Hermitage held masterpieces on a par with those of any museum in the world, but it lacked what you'd take for granted in the West: fresh paint on the walls, central air conditioning, a pristine gift shop. The boulevards were grand, but trash piled up on the sidewalks. In parks, menacing-looking men drank out of tall cans. Even the beer had an edge to it, a higher alcohol content that could more quickly make you forget whatever it was you didn't want to remember. On the train ride out of the country, I fell asleep and my camera was stolen out of my backpack. By contrast, the Baltic capitals were largely refurbished, on their way to becoming newly embraced members of the Western clubs-the European Union, NATO. Visiting the Baltics in 2001 was like going to a neighborhood in Brooklyn on the cusp of gentrification.

Kaliningrad, by contrast, felt forgotten by time. The only foreign tourists there other than stray backpackers like me were busloads of Germans, hoping to reconnect with some lost piece of their heritage. They walked in packs, cameras around their necks, the losers of World War II now exponentially wealthier than the Russians who'd conquered them and repopulated their city.

Among the low-rise apartment blocks and storefronts, a tower loomed. The House of Soviets was visible from almost all parts of the city. Construction had begun on the building more than forty years earlier, in 1970, among the ruins of the old Königsberg castle. The House of Soviets would be a living symbol of the fact that Communism triumphed over fascism. But the impulse for triumphalism backfired because the wet soil that the castle ruins sat on was like quicksand beneath the Soviet tower. Once the House of Soviets reached twenty-one stories, the engineers realized that it wasn't going to be safe to complete without risking collapse. Construction was halted in the 1980s, and the giant structure stood empty until I laid eyes on it, an unfinished ruin. It did not take a literary mind to see the unpleasant concrete structure as a metaphor for the Soviet Union itself: an ideal that triumphed in war but proved incapable of meeting the basic needs of human beings or keeping pace with a changing world.

I passed a couple of uneven...

The House of Soviets

For much of the twenty-first century, Russia has led the counterrevolution to American domination-not by seeking to upend the global order that America constructed, but rather by disrupting it from within, turning it (and ultimately America itself) into the ugliest version of itself. I think of how Russians must have seen us Americans as I was growing up: capitalist stooges, driven entirely by a lust for profit; a militarized empire, unconcerned with the lives of the distant people harmed by our foreign policies; racist hypocrites, preaching human rights abroad and practicing systemic oppression at home. That's the America that Putin wants the world to see, and that's the America that Putin wants us to be.

Think about it. Isn't that what you would want for someone that humiliated you? For them to be revealed, before the world, as the worst version of themselves? By doing so, Putin leveled the playing field-the world is what it is, a hard place in which might makes right, capitalism is as fungible as Communism, and a ruthless Russia will always have to be treated with the respect that it was denied after the wall came crashing down.

The city of Kaliningrad is one of those oddities of history, traded back and forth between empires and nation-states, swapping languages and ethnic majorities, caught in the shifting currents of history. Nestled between Poland and Lithuania along the Baltic Sea, it used to be the German city of Königsberg even though it didn't border Germany. After its brutal conquest by the Red Army, the city was renamed, Stalin repopulated it with Russians, and Kaliningrad served as the home for the Soviet Baltic fleet during the Cold War (as well as the home for some unverifiable number of nuclear weapons). After the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the Russians hung on to Kaliningrad even as neighboring Lithuania became free, leaving the city once again cut off from its nation-a part of Russia, two hundred miles from the Russian border. It was this peculiar political identity that drew me there in the summer of 2001-a twenty-three-year-old part-time teacher and graduate student with little idea what I was going to do with the rest of my life.

Before I got to Kaliningrad, I set foot on Russian soil for the first time, traveling through St. Petersburg and then the three Baltic nations, independent states for just a decade. St. Petersburg-Putin's hometown-seemed to be covered in a layer of dust. The Hermitage held masterpieces on a par with those of any museum in the world, but it lacked what you'd take for granted in the West: fresh paint on the walls, central air conditioning, a pristine gift shop. The boulevards were grand, but trash piled up on the sidewalks. In parks, menacing-looking men drank out of tall cans. Even the beer had an edge to it, a higher alcohol content that could more quickly make you forget whatever it was you didn't want to remember. On the train ride out of the country, I fell asleep and my camera was stolen out of my backpack. By contrast, the Baltic capitals were largely refurbished, on their way to becoming newly embraced members of the Western clubs-the European Union, NATO. Visiting the Baltics in 2001 was like going to a neighborhood in Brooklyn on the cusp of gentrification.

Kaliningrad, by contrast, felt forgotten by time. The only foreign tourists there other than stray backpackers like me were busloads of Germans, hoping to reconnect with some lost piece of their heritage. They walked in packs, cameras around their necks, the losers of World War II now exponentially wealthier than the Russians who'd conquered them and repopulated their city.

Among the low-rise apartment blocks and storefronts, a tower loomed. The House of Soviets was visible from almost all parts of the city. Construction had begun on the building more than forty years earlier, in 1970, among the ruins of the old Königsberg castle. The House of Soviets would be a living symbol of the fact that Communism triumphed over fascism. But the impulse for triumphalism backfired because the wet soil that the castle ruins sat on was like quicksand beneath the Soviet tower. Once the House of Soviets reached twenty-one stories, the engineers realized that it wasn't going to be safe to complete without risking collapse. Construction was halted in the 1980s, and the giant structure stood empty until I laid eyes on it, an unfinished ruin. It did not take a literary mind to see the unpleasant concrete structure as a metaphor for the Soviet Union itself: an ideal that triumphed in war but proved incapable of meeting the basic needs of human beings or keeping pace with a changing world.

I passed a couple of uneven...