Community & Culture

- Publisher : Anchor

- Published : 27 Sep 2022

- Pages : 320

- ISBN-10 : 0593313003

- ISBN-13 : 9780593313008

- Language : English

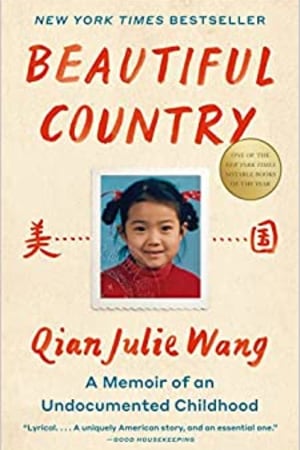

Beautiful Country: A Memoir of an Undocumented Childhood

A NEW YORK TIMES BEST SELLER • The moving story of an undocumented child living in poverty in the richest country in the world-an incandescent debut from an astonishing new talent • A TODAY SHOW #READWITHJENNA PICK

In Chinese, the word for America, Mei Guo, translates directly to "beautiful country." Yet when seven-year-old Qian arrives in New York City in 1994 full of curiosity, she is overwhelmed by crushing fear and scarcity. In China, Qian's parents were professors; in America, her family is "illegal" and it will require all the determination and small joys they can muster to survive.

In Chinatown, Qian's parents labor in sweatshops. Instead of laughing at her jokes, they fight constantly, taking out the stress of their new life on one another. Shunned by her classmates and teachers for her limited English, Qian takes refuge in the library and masters the language through books, coming to think of The Berenstain Bears as her first American friends. And where there is delight to be found, Qian relishes it: her first bite of gloriously greasy pizza, weekly "shopping days," when Qian finds small treasures in the trash lining Brooklyn's streets, and a magical Christmas visit to Rockefeller Center-confirmation that the New York City she saw in movies does exist after all.

But then Qian's headstrong Ma Ma collapses, revealing an illness that she has kept secret for months for fear of the cost and scrutiny of a doctor's visit. As Ba Ba retreats further inward, Qian has little to hold onto beyond his constant refrain: Whatever happens, say that you were born here, that you've always lived here.

Inhabiting her childhood perspective with exquisite lyric clarity and unforgettable charm and strength, Qian Julie Wang has penned an essential American story about a family fracturing under the weight of invisibility, and a girl coming of age in the shadows, who never stops seeking the light.

In Chinese, the word for America, Mei Guo, translates directly to "beautiful country." Yet when seven-year-old Qian arrives in New York City in 1994 full of curiosity, she is overwhelmed by crushing fear and scarcity. In China, Qian's parents were professors; in America, her family is "illegal" and it will require all the determination and small joys they can muster to survive.

In Chinatown, Qian's parents labor in sweatshops. Instead of laughing at her jokes, they fight constantly, taking out the stress of their new life on one another. Shunned by her classmates and teachers for her limited English, Qian takes refuge in the library and masters the language through books, coming to think of The Berenstain Bears as her first American friends. And where there is delight to be found, Qian relishes it: her first bite of gloriously greasy pizza, weekly "shopping days," when Qian finds small treasures in the trash lining Brooklyn's streets, and a magical Christmas visit to Rockefeller Center-confirmation that the New York City she saw in movies does exist after all.

But then Qian's headstrong Ma Ma collapses, revealing an illness that she has kept secret for months for fear of the cost and scrutiny of a doctor's visit. As Ba Ba retreats further inward, Qian has little to hold onto beyond his constant refrain: Whatever happens, say that you were born here, that you've always lived here.

Inhabiting her childhood perspective with exquisite lyric clarity and unforgettable charm and strength, Qian Julie Wang has penned an essential American story about a family fracturing under the weight of invisibility, and a girl coming of age in the shadows, who never stops seeking the light.

Editorial Reviews

A NEW YORK TIMES NOTABLE BOOK • ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR: The New York Times, NPR, Publishers Weekly, The Guardian, Good Housekeeping, She Reads, and more • One of President Obama's Favorite Books of the Year

"Incredibly important, exquisitely written, harrowing. . . Beautiful Country tells [Wang's] story, well, quite beautifully. It is not only Wang's mastery of the language that makes the story so compelling, but also the passionate yearning for empathy and understanding. Beautiful Country is timely, yes, but more importantly it is a near-masterpiece that will make Qian Julie Wang a literary star."-Shondaland

"For fans of Angela's Ashes and The Glass Castle."-Newsday

"[An] exquisitely crafted memoir."-Oprah Daily

"A heartbreaking and intimate memoir... the storytelling from a young Qian's perspective is riveting."-Politico

"This unforgettable memoir is eye-opening to the nth degree."-Real Simple

"Elegantly affecting."-The Guardian

"A coming-of-age memoir about an undocumented Chinese girl growing up in New York's Chinatown, this lyrical book is full of small moments of joy, heartbreaking pain and the struggles of a family trying to survive in the shadows of society. It's a uniquely American story, and an essential one."...

"Incredibly important, exquisitely written, harrowing. . . Beautiful Country tells [Wang's] story, well, quite beautifully. It is not only Wang's mastery of the language that makes the story so compelling, but also the passionate yearning for empathy and understanding. Beautiful Country is timely, yes, but more importantly it is a near-masterpiece that will make Qian Julie Wang a literary star."-Shondaland

"For fans of Angela's Ashes and The Glass Castle."-Newsday

"[An] exquisitely crafted memoir."-Oprah Daily

"A heartbreaking and intimate memoir... the storytelling from a young Qian's perspective is riveting."-Politico

"This unforgettable memoir is eye-opening to the nth degree."-Real Simple

"Elegantly affecting."-The Guardian

"A coming-of-age memoir about an undocumented Chinese girl growing up in New York's Chinatown, this lyrical book is full of small moments of joy, heartbreaking pain and the struggles of a family trying to survive in the shadows of society. It's a uniquely American story, and an essential one."...

Readers Top Reviews

Sadiah WSatisfied

A powerful read through the eyes of an undocumented child- in this moving memoir, Qian Julie Wang gives voice to the young girl she once was, navigating the reader through often difficult/complex life experiences and lessons she was forced to learn at a young age due to her and her parents undocumented life. References to her former life in China is contrasted often with the American experience. What made me reflect most whilst reading this book on a personal level, is the strong sense of dependance, fragility, vulnerability that often accompanies a child, due to the choices one’s parents make, which can both have a positive and negative impact. But also, this memoir served as an example of how our life experiences and sometimes even our traumas, have the power to not only transform us, but also possess the potential to inevitably provide us with the knowledge and resilience we need to become who we want to be.

Heather L. HurdSa

This is such a poignant, emotional story of immigrant life and the fallacy of the american dream. Seeing through the eyes of an immigrant child brings painful reality to every dark detail.

Ruth Gunter Mitch

Wang has me turning pages as quickly as I can to see how she gets from China to her present career. Her story brings me to tears of compassion and to cheers for her triumphs. Although I have not walked in her shoes as a frightened immigrant, she causes me to worry and fear for her path to peace. In my opinion, Wang’s book deserves a spot on required reading lists for all American students. Her writing itself is a model of perfection to be appreciated. I am most grateful to her for exposing her truth regardless of the pain it causes her.

Norfolk buyerRuth

Qian’s memoir is riveting, powerful, sad, and hopeful all at once. It tells the complex, hard story of immigration to the US in a poignant and personal way. Her voice is at once matter-of-fact and poetic. Her love for her parents is unflinching.

IsobelSilka AirdN

I have read the book and listened to several interviews with Wang. While I have no doubt that she and her family had a hard time upon arrival in the U.S. and I am sure it was difficult living in the shadows fearing deportation, I am confused by the assertion that her story illustrates the fallacy of the American dream. She is a Yale Law grad and a partner in her own law firm. That seems rather successful to me. Could she have achieved this level of success in China - with a dissident uncle who was arrested and tortured and a father under watch to the point he felt he had to flee or face the same fate as his brother. And would she have been able to write a book trashing China - while living in China - and become even more successful? Somehow I doubt it. She talks about how much more open Canada was to her family. However, apparently her mother worked through a lawyer and petitioned Canada for legal entry as an educated person. Had they followed U.S. immigration rules and petitioned on the same basis, instead of illegally overstaying visas in the U.S., how do we know they would have been denied? At one point in one of her interviews, while talking about how books saved her, she says she identified with some of the characters. She specifically mentions Anne Frank and says she felt a kinship with her as she, herself, was "living in the shadows." While on some level, that may be somewhat true, it is jarring to hear her compare her childhood with a person confined to a room, never allowed to leave, living with the potential of - and finally actual - seizure and extermination. That comparison is even more disconcerting when, in the same interview, she says as a child she loved living in China where everyone looked like her, she had plenty of food, and there was no fear of lacking documents or punishment for same - all of which was so very different from the U.S. where she was constantly discriminated against, was nearly starving, and in constant fear of deportation. Um what, exactly was so bad about deportation if China was so much better than the U.S.? And how, exactly, did that compare to Ann Frank's fate? Now I get that as an adult, she may have realized that China was not the paradise she thought it was as a child, but in the interview, she is talking about her fear - as a child -of being sent back there. Also, while extolling Canada as so much better than the U.S. in terms of welcoming immigrants, I fail to understand - first why she didn't stay there since it was so much better and second, why she doesn't advise her current immigrant clients to go there. Could it be because many of her clients are here illegally without the skills and education her parents had and she knows full well they would not be successful in legal entry to Canada after all? I am glad she has made a success of her...

Short Excerpt Teaser

How It Began

My story starts decades before my birth.

In my father's earliest memory, he is four years old, shooting a toy gun at nearby birds as he skips to the town square. There he halts, arrested by curious, swaying shapes that he is slow to recognize: two men dangling from a muscular tree.

He approaches slowly, pushing past the knees of adults encircling the tree. In the muggy late-summer air, mosquitoes and flies swarm the hanging corpses. The stench of decomposing flesh floods his nose.

He sees on the dirt ground a single character written in blood:

冤

Wrongly accused.

It is 1966 and China's Cultural Revolution has just begun. Even for a country marked by storied upheaval, the next decade would bring unparalleled turmoil. To this date, the actual death toll from the purges remains unspoken and, worse, unknown.

* * *

Three years later, my seven-year-old father watched as his eldest brother was placed under arrest. Weeks prior, my teenage uncle had criticized Mao Zedong in writing for manipulating the innocent people of China by pitting them against one another, just to centralize his power. My uncle had naïvely, heroically, stupidly signed his name to the essay and distributed it.

So there would be no high school graduation for him, only starvation and torture behind prison walls.

From then on, my father would spend his childhood bearing witness to his parents' public beatings, all while enduring his own humiliation at school, where he was forced to stand in the front of the classroom every morning as his teachers and classmates berated him and his "treasonous" family. Outside of school, adults and children alike pelted him with rocks, pebbles, shit. Gone was the honor of his grandfather, whose deft brokering had managed to shield their village from the rape and pillage of the Japanese occupation. Gone were the visitors to the Wang family courtyard who sought his father's calligraphy. From then on, it would just be his mother's bruised face. His father's silent, stoic tears. His four sisters' screams as the Red Guards ransacked their already shredded home.

It is against this backdrop that my parents' beginnings unfurled. My mother's pain was that of a daughter born to a family entangled in the government. None of her father's power was enough to insulate her from the unrest and sexism of her time. She grew up a hundred miles away from my father, and their hardships were at once the same and worlds apart.

Half a century and a migration across the world later, it would take therapy's slow and arduous unraveling for me to see that the thread of trauma was woven into every fiber of my family, my childhood.

* * *

On July 29, 1994, I arrived at JFK Airport on a visa that would expire much too quickly. Five days prior, I had turned seven years old, the same age at which my father had begun his daily wrestle with shame. My parents and I would spend the next five years in the furtive shadows of New York City, pushing past hunger pangs to labor at menial jobs, with no rights, no access to medical care, no hope of legality. The Chinese refer to being undocumented colloquially as "hei": being in the dark, being blacked out. And aptly so, because we spent those years shrouded in darkness while wrestling with hope and dignity.

Memory is a fickle thing, but other than names and certain identifying details-which I have changed out of respect for others' privacy-I have endeavored to document my family's undocumented years as authentically and intimately as possible. I regret that I can do no justice to my father's childhood, for it is pockmarked by more despair than I can ever know.

In some ways, this project has always been in me, but in a much larger way, I have the 2016 election to thank. I took my first laughable stab at this project during my college years, writing it as fiction, not understanding that it was impossible to find perspective on a still-festering wound.

After graduating from Yale Law School-where I could not have fit in less-I clerked for a federal appellate judge who instilled in me, even beyond my greatest, most idealistic hopes, an abiding faith in justice. During that clerkship year, I watched as the Obama administration talked out of both sides of its mouth, at once championing deferred action for Dreamers while issuing deportations at unprecedented rates. By the time the immigration cases got to our chambers on appeal, there was often very little my judge could do.

In May 2016, just shy of eight thousand days after I first landed in New York City-the only place my heart and spirit call home-I finally became a U.S. citizen. My...

My story starts decades before my birth.

In my father's earliest memory, he is four years old, shooting a toy gun at nearby birds as he skips to the town square. There he halts, arrested by curious, swaying shapes that he is slow to recognize: two men dangling from a muscular tree.

He approaches slowly, pushing past the knees of adults encircling the tree. In the muggy late-summer air, mosquitoes and flies swarm the hanging corpses. The stench of decomposing flesh floods his nose.

He sees on the dirt ground a single character written in blood:

冤

Wrongly accused.

It is 1966 and China's Cultural Revolution has just begun. Even for a country marked by storied upheaval, the next decade would bring unparalleled turmoil. To this date, the actual death toll from the purges remains unspoken and, worse, unknown.

* * *

Three years later, my seven-year-old father watched as his eldest brother was placed under arrest. Weeks prior, my teenage uncle had criticized Mao Zedong in writing for manipulating the innocent people of China by pitting them against one another, just to centralize his power. My uncle had naïvely, heroically, stupidly signed his name to the essay and distributed it.

So there would be no high school graduation for him, only starvation and torture behind prison walls.

From then on, my father would spend his childhood bearing witness to his parents' public beatings, all while enduring his own humiliation at school, where he was forced to stand in the front of the classroom every morning as his teachers and classmates berated him and his "treasonous" family. Outside of school, adults and children alike pelted him with rocks, pebbles, shit. Gone was the honor of his grandfather, whose deft brokering had managed to shield their village from the rape and pillage of the Japanese occupation. Gone were the visitors to the Wang family courtyard who sought his father's calligraphy. From then on, it would just be his mother's bruised face. His father's silent, stoic tears. His four sisters' screams as the Red Guards ransacked their already shredded home.

It is against this backdrop that my parents' beginnings unfurled. My mother's pain was that of a daughter born to a family entangled in the government. None of her father's power was enough to insulate her from the unrest and sexism of her time. She grew up a hundred miles away from my father, and their hardships were at once the same and worlds apart.

Half a century and a migration across the world later, it would take therapy's slow and arduous unraveling for me to see that the thread of trauma was woven into every fiber of my family, my childhood.

* * *

On July 29, 1994, I arrived at JFK Airport on a visa that would expire much too quickly. Five days prior, I had turned seven years old, the same age at which my father had begun his daily wrestle with shame. My parents and I would spend the next five years in the furtive shadows of New York City, pushing past hunger pangs to labor at menial jobs, with no rights, no access to medical care, no hope of legality. The Chinese refer to being undocumented colloquially as "hei": being in the dark, being blacked out. And aptly so, because we spent those years shrouded in darkness while wrestling with hope and dignity.

Memory is a fickle thing, but other than names and certain identifying details-which I have changed out of respect for others' privacy-I have endeavored to document my family's undocumented years as authentically and intimately as possible. I regret that I can do no justice to my father's childhood, for it is pockmarked by more despair than I can ever know.

In some ways, this project has always been in me, but in a much larger way, I have the 2016 election to thank. I took my first laughable stab at this project during my college years, writing it as fiction, not understanding that it was impossible to find perspective on a still-festering wound.

After graduating from Yale Law School-where I could not have fit in less-I clerked for a federal appellate judge who instilled in me, even beyond my greatest, most idealistic hopes, an abiding faith in justice. During that clerkship year, I watched as the Obama administration talked out of both sides of its mouth, at once championing deferred action for Dreamers while issuing deportations at unprecedented rates. By the time the immigration cases got to our chambers on appeal, there was often very little my judge could do.

In May 2016, just shy of eight thousand days after I first landed in New York City-the only place my heart and spirit call home-I finally became a U.S. citizen. My...