Community & Culture

- Publisher : Avid Reader Press / Simon & Schuster

- Published : 05 Sep 2023

- Pages : 352

- ISBN-10 : 198218647X

- ISBN-13 : 9781982186470

- Language : English

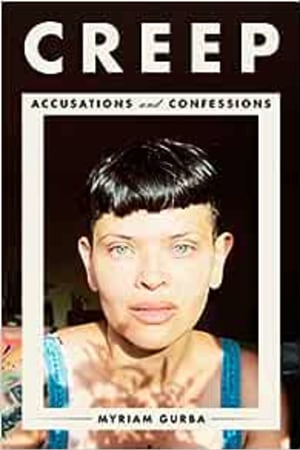

Creep: Accusations and Confessions

A ruthless and razor-sharp essay collection that tackles the pervasive, creeping oppression and toxicity that has wormed its way into society-in our books, schools, and homes, as well as the systems that perpetuate them-from the acclaimed author of Mean, and one of our fiercest, foremost explorers of intersectional Latinx identity.

A creep can be a singular figure, a villain who makes things go bump in the night. Yet creep is also what the fog does-it lurks into place to do its dirty work, muffling screams, obscuring the truth, and providing cover for those prowling within it.

Creep is Myriam Gurba's informal sociology of creeps, a deep dive into the dark recesses of the toxic traditions that plague the United States and create the abusers who haunt our books, schools, and homes. Through cultural criticism disguised as personal essay, Gurba studies the ways in which oppression is collectively enacted, sustaining ecosystems that unfairly distribute suffering and premature death to our most vulnerable. Yet identifying individual creeps, creepy social groups, and creepy cultures is only half of this book's project-the other half is examining how we as individuals, communities, and institutions can challenge creeps and rid ourselves of the fog that seeks to blind us.

With her ruthless mind, wry humor, and adventurous style, Gurba implicates everyone from Joan Didion to her former abuser, everything from Mexican stereotypes to the carceral state. Braiding her own history and identity throughout, she argues for a new way of conceptualizing oppression, and she does it with her signature blend of bravado and humility.

A creep can be a singular figure, a villain who makes things go bump in the night. Yet creep is also what the fog does-it lurks into place to do its dirty work, muffling screams, obscuring the truth, and providing cover for those prowling within it.

Creep is Myriam Gurba's informal sociology of creeps, a deep dive into the dark recesses of the toxic traditions that plague the United States and create the abusers who haunt our books, schools, and homes. Through cultural criticism disguised as personal essay, Gurba studies the ways in which oppression is collectively enacted, sustaining ecosystems that unfairly distribute suffering and premature death to our most vulnerable. Yet identifying individual creeps, creepy social groups, and creepy cultures is only half of this book's project-the other half is examining how we as individuals, communities, and institutions can challenge creeps and rid ourselves of the fog that seeks to blind us.

With her ruthless mind, wry humor, and adventurous style, Gurba implicates everyone from Joan Didion to her former abuser, everything from Mexican stereotypes to the carceral state. Braiding her own history and identity throughout, she argues for a new way of conceptualizing oppression, and she does it with her signature blend of bravado and humility.

Editorial Reviews

1. Tell TELL

It's easy to get sucked into playing morbid games. When I was little, I happily went along with a few.

I played one with Renee Jr., the daughter of the woman who gave me my second perm. She and Renee Sr. lived in a tall apartment building across the street from the used bookstore where I sometimes spent my allowance. Sycamore trees towered in a nearby park, and when their leaves turned penny-colored and crunchy, falling and carpeting the grass, they created the illusion that we lived somewhere that experienced passionate seasons. Santa Maria's seasons could be hard to detect. The closest we came to getting snow were whispers of frost that half dusted our station wagon's windshield, hardly enough to write your name in.

Renee Sr.'s face was as gorgeous as my mother's. The scar above her lip accented her beauty. Above her living room TV hung a framed cross-stitch, God Bless Our Pad. I sat on a black dining room chair in the kitchen, trying to look out the window above the sink. The sky was a boring blue. Cars chugged along Main Street. A gust of wind sent sycamore leaves scattering. Renee Sr. gathered my hair in her hands, winding it around rollers. The ragged cash my mother had paid her was stacked on the kitchen counter. Beside the money, chicken thighs defrosted.

My feet rubbed the spotless linoleum floor. I liked the sensation of my tight socks gliding against it.

"Hold still," said Renee Sr. "Quit squirming." Renee Sr. had a perm and an odd, impatient voice. She sounded how I imagined an ant would. Dangerously high-pitched. Venomous.

Once her mother was done setting my hair, a grinning Renee Jr. waved at me, inviting me to her bedroom. I accepted. Renee Jr. had inherited her mother's beauty, accented by long teeth instead of a knotty scar.

Renee Jr. and I knelt on her chocolate-colored carpet. The apartment, including her room, smelled of buttered flour tortillas and fabric softener. The scent made me feel held, safe, and I couldn't wait to rinse the perm solution out of my hair so that I could sniff that fragrance again. The stuff Renee Sr. had squirted on me made my head stink and my scalp burn.

Renee Jr. dumped a pile of Barbie dolls between us. Lifting one by her asymmetrical pageboy, I asked, "You're allowed to cut their hair?"

Renee Jr. petted a blonde and nodded.

"They're mine," she said. "I can do whatever I want to them."

I tried not to act envious. I wasn't allowed to cut my dolls' hair or my own. My mother had put that rule in place after I tried giving myself Cleopatra bangs.

With the bedroom door closed, Renee Jr.'s dolls enacted scenes inspired by US and Latin-American soap operas. They yelled, wept, shook, and made murde...

It's easy to get sucked into playing morbid games. When I was little, I happily went along with a few.

I played one with Renee Jr., the daughter of the woman who gave me my second perm. She and Renee Sr. lived in a tall apartment building across the street from the used bookstore where I sometimes spent my allowance. Sycamore trees towered in a nearby park, and when their leaves turned penny-colored and crunchy, falling and carpeting the grass, they created the illusion that we lived somewhere that experienced passionate seasons. Santa Maria's seasons could be hard to detect. The closest we came to getting snow were whispers of frost that half dusted our station wagon's windshield, hardly enough to write your name in.

Renee Sr.'s face was as gorgeous as my mother's. The scar above her lip accented her beauty. Above her living room TV hung a framed cross-stitch, God Bless Our Pad. I sat on a black dining room chair in the kitchen, trying to look out the window above the sink. The sky was a boring blue. Cars chugged along Main Street. A gust of wind sent sycamore leaves scattering. Renee Sr. gathered my hair in her hands, winding it around rollers. The ragged cash my mother had paid her was stacked on the kitchen counter. Beside the money, chicken thighs defrosted.

My feet rubbed the spotless linoleum floor. I liked the sensation of my tight socks gliding against it.

"Hold still," said Renee Sr. "Quit squirming." Renee Sr. had a perm and an odd, impatient voice. She sounded how I imagined an ant would. Dangerously high-pitched. Venomous.

Once her mother was done setting my hair, a grinning Renee Jr. waved at me, inviting me to her bedroom. I accepted. Renee Jr. had inherited her mother's beauty, accented by long teeth instead of a knotty scar.

Renee Jr. and I knelt on her chocolate-colored carpet. The apartment, including her room, smelled of buttered flour tortillas and fabric softener. The scent made me feel held, safe, and I couldn't wait to rinse the perm solution out of my hair so that I could sniff that fragrance again. The stuff Renee Sr. had squirted on me made my head stink and my scalp burn.

Renee Jr. dumped a pile of Barbie dolls between us. Lifting one by her asymmetrical pageboy, I asked, "You're allowed to cut their hair?"

Renee Jr. petted a blonde and nodded.

"They're mine," she said. "I can do whatever I want to them."

I tried not to act envious. I wasn't allowed to cut my dolls' hair or my own. My mother had put that rule in place after I tried giving myself Cleopatra bangs.

With the bedroom door closed, Renee Jr.'s dolls enacted scenes inspired by US and Latin-American soap operas. They yelled, wept, shook, and made murde...

Short Excerpt Teaser

1. Tell TELL

It's easy to get sucked into playing morbid games. When I was little, I happily went along with a few.

I played one with Renee Jr., the daughter of the woman who gave me my second perm. She and Renee Sr. lived in a tall apartment building across the street from the used bookstore where I sometimes spent my allowance. Sycamore trees towered in a nearby park, and when their leaves turned penny-colored and crunchy, falling and carpeting the grass, they created the illusion that we lived somewhere that experienced passionate seasons. Santa Maria's seasons could be hard to detect. The closest we came to getting snow were whispers of frost that half dusted our station wagon's windshield, hardly enough to write your name in.

Renee Sr.'s face was as gorgeous as my mother's. The scar above her lip accented her beauty. Above her living room TV hung a framed cross-stitch, God Bless Our Pad. I sat on a black dining room chair in the kitchen, trying to look out the window above the sink. The sky was a boring blue. Cars chugged along Main Street. A gust of wind sent sycamore leaves scattering. Renee Sr. gathered my hair in her hands, winding it around rollers. The ragged cash my mother had paid her was stacked on the kitchen counter. Beside the money, chicken thighs defrosted.

My feet rubbed the spotless linoleum floor. I liked the sensation of my tight socks gliding against it.

"Hold still," said Renee Sr. "Quit squirming." Renee Sr. had a perm and an odd, impatient voice. She sounded how I imagined an ant would. Dangerously high-pitched. Venomous.

Once her mother was done setting my hair, a grinning Renee Jr. waved at me, inviting me to her bedroom. I accepted. Renee Jr. had inherited her mother's beauty, accented by long teeth instead of a knotty scar.

Renee Jr. and I knelt on her chocolate-colored carpet. The apartment, including her room, smelled of buttered flour tortillas and fabric softener. The scent made me feel held, safe, and I couldn't wait to rinse the perm solution out of my hair so that I could sniff that fragrance again. The stuff Renee Sr. had squirted on me made my head stink and my scalp burn.

Renee Jr. dumped a pile of Barbie dolls between us. Lifting one by her asymmetrical pageboy, I asked, "You're allowed to cut their hair?"

Renee Jr. petted a blonde and nodded.

"They're mine," she said. "I can do whatever I want to them."

I tried not to act envious. I wasn't allowed to cut my dolls' hair or my own. My mother had put that rule in place after I tried giving myself Cleopatra bangs.

With the bedroom door closed, Renee Jr.'s dolls enacted scenes inspired by US and Latin-American soap operas. They yelled, wept, shook, and made murderous threats. They lied and broke promises. They trembled, got naked, and banged stiff pubic areas. Clack, clack, clack. They slapped and bit. They hurt one another on purpose and laughed instead of apologizing. They cheated, broke up, got back together, and cheated again.

They were lesbians.

They had no choice.

Renee Jr. had no male dolls.

Renee Jr. carried a distraught lesbian to the open window. I hurried after her.

She shrieked, "I can't take it anymore! I'm gonna jump!"

Silhouetted against the boring blue, we watched the doll go up, pause, and then plummet. Face-first, she smacked the ground unceremoniously.

She's dead, I thought.

Renee Jr. and I looked at each other. Smiled. We had discovered something fun. Throwing dolls out the window and watching them fall ten stories was something we probably weren't supposed to be doing. Soon, all of Renee Jr.'s dolls were scattered along the sidewalk beneath her window, contorted in death poses, and we had nothing left to play with but ourselves.

My parents owned a book with glossy reproductions of paintings and drawings by Frida Kahlo. One of the paintings, The Suicide of Dorothy Hale, looked like the game invented by Renee Jr.

I was growing out my perm. I liked the one Renee Sr. had given me better than the first one I'd gotten, but I didn't plan on getting a third.

Gilda's mother and mine were downstairs drinking coffee and gossiping in Spanish. Gilda's mother spoke Spanish Spanish. She was Spanish and had a challenging nickname. In Spanish Spanish, the nickname didn't mean anything. It was cute gibberish. In Mexican Spanish, it meant underwear.

Regina, Gilda's across-the-cul-de-sac neighbor, was with us. We were gathered in Gilda's bedroom, and I was wearing a shawl, white wig, and granny glasses. Gilda had told me to put these ...

It's easy to get sucked into playing morbid games. When I was little, I happily went along with a few.

I played one with Renee Jr., the daughter of the woman who gave me my second perm. She and Renee Sr. lived in a tall apartment building across the street from the used bookstore where I sometimes spent my allowance. Sycamore trees towered in a nearby park, and when their leaves turned penny-colored and crunchy, falling and carpeting the grass, they created the illusion that we lived somewhere that experienced passionate seasons. Santa Maria's seasons could be hard to detect. The closest we came to getting snow were whispers of frost that half dusted our station wagon's windshield, hardly enough to write your name in.

Renee Sr.'s face was as gorgeous as my mother's. The scar above her lip accented her beauty. Above her living room TV hung a framed cross-stitch, God Bless Our Pad. I sat on a black dining room chair in the kitchen, trying to look out the window above the sink. The sky was a boring blue. Cars chugged along Main Street. A gust of wind sent sycamore leaves scattering. Renee Sr. gathered my hair in her hands, winding it around rollers. The ragged cash my mother had paid her was stacked on the kitchen counter. Beside the money, chicken thighs defrosted.

My feet rubbed the spotless linoleum floor. I liked the sensation of my tight socks gliding against it.

"Hold still," said Renee Sr. "Quit squirming." Renee Sr. had a perm and an odd, impatient voice. She sounded how I imagined an ant would. Dangerously high-pitched. Venomous.

Once her mother was done setting my hair, a grinning Renee Jr. waved at me, inviting me to her bedroom. I accepted. Renee Jr. had inherited her mother's beauty, accented by long teeth instead of a knotty scar.

Renee Jr. and I knelt on her chocolate-colored carpet. The apartment, including her room, smelled of buttered flour tortillas and fabric softener. The scent made me feel held, safe, and I couldn't wait to rinse the perm solution out of my hair so that I could sniff that fragrance again. The stuff Renee Sr. had squirted on me made my head stink and my scalp burn.

Renee Jr. dumped a pile of Barbie dolls between us. Lifting one by her asymmetrical pageboy, I asked, "You're allowed to cut their hair?"

Renee Jr. petted a blonde and nodded.

"They're mine," she said. "I can do whatever I want to them."

I tried not to act envious. I wasn't allowed to cut my dolls' hair or my own. My mother had put that rule in place after I tried giving myself Cleopatra bangs.

With the bedroom door closed, Renee Jr.'s dolls enacted scenes inspired by US and Latin-American soap operas. They yelled, wept, shook, and made murderous threats. They lied and broke promises. They trembled, got naked, and banged stiff pubic areas. Clack, clack, clack. They slapped and bit. They hurt one another on purpose and laughed instead of apologizing. They cheated, broke up, got back together, and cheated again.

They were lesbians.

They had no choice.

Renee Jr. had no male dolls.

Renee Jr. carried a distraught lesbian to the open window. I hurried after her.

She shrieked, "I can't take it anymore! I'm gonna jump!"

Silhouetted against the boring blue, we watched the doll go up, pause, and then plummet. Face-first, she smacked the ground unceremoniously.

She's dead, I thought.

Renee Jr. and I looked at each other. Smiled. We had discovered something fun. Throwing dolls out the window and watching them fall ten stories was something we probably weren't supposed to be doing. Soon, all of Renee Jr.'s dolls were scattered along the sidewalk beneath her window, contorted in death poses, and we had nothing left to play with but ourselves.

My parents owned a book with glossy reproductions of paintings and drawings by Frida Kahlo. One of the paintings, The Suicide of Dorothy Hale, looked like the game invented by Renee Jr.

I was growing out my perm. I liked the one Renee Sr. had given me better than the first one I'd gotten, but I didn't plan on getting a third.

Gilda's mother and mine were downstairs drinking coffee and gossiping in Spanish. Gilda's mother spoke Spanish Spanish. She was Spanish and had a challenging nickname. In Spanish Spanish, the nickname didn't mean anything. It was cute gibberish. In Mexican Spanish, it meant underwear.

Regina, Gilda's across-the-cul-de-sac neighbor, was with us. We were gathered in Gilda's bedroom, and I was wearing a shawl, white wig, and granny glasses. Gilda had told me to put these ...