Diseases & Physical Ailments

- Publisher : Avid Reader Press / Simon & Schuster

- Published : 06 Jun 2023

- Pages : 272

- ISBN-10 : 1668016508

- ISBN-13 : 9781668016503

- Language : English

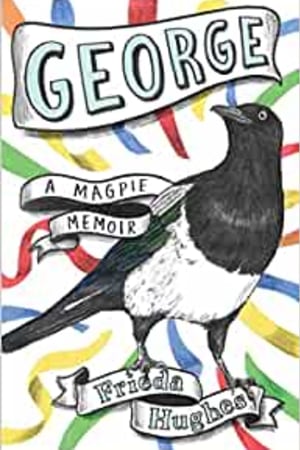

George: A Magpie Memoir

"He was a hectic, unprincipled bird, but it was impossible not to love him." From poet and painter Frieda Hughes, a memoir of love, obsession, and feathers.

When Frieda Hughes moved to the depths of the Welsh countryside, she was expecting to take on a few projects: planting a garden, painting, writing her poetry column for The Times (London), and possibly even breathing new life into her ailing marriage. But instead, she found herself rescuing a baby magpie, the sole survivor of a nest destroyed in a storm-and embarking on an obsession that would change the course of her life.

As the magpie, George, grows from a shrieking scrap of feathers and bones into an intelligent, unruly companion, Frieda finds herself captivated-and apprehensive of what will happen when the time comes to finally set him free.

With irresistible humor and heart, Frieda invites us along on her unlikely journey toward joy and connection in the wake of sadness and loss; a journey that began with saving a tiny wild creature and ended with her being saved in return.

When Frieda Hughes moved to the depths of the Welsh countryside, she was expecting to take on a few projects: planting a garden, painting, writing her poetry column for The Times (London), and possibly even breathing new life into her ailing marriage. But instead, she found herself rescuing a baby magpie, the sole survivor of a nest destroyed in a storm-and embarking on an obsession that would change the course of her life.

As the magpie, George, grows from a shrieking scrap of feathers and bones into an intelligent, unruly companion, Frieda finds herself captivated-and apprehensive of what will happen when the time comes to finally set him free.

With irresistible humor and heart, Frieda invites us along on her unlikely journey toward joy and connection in the wake of sadness and loss; a journey that began with saving a tiny wild creature and ended with her being saved in return.

Editorial Reviews

"George the magpie trashes the author's house, terrifies the cleaning lady, and helps tank her failing marriage-and yet you cannot help falling madly in love with him. Frieda Hughes observes this little black and white bird with the meticulous eye of a naturalist and the penetrating lyricism of a poet. This book is a joy from beginning to end."-Sy Montgomery, New York Times bestselling author of The Soul of an Octopus

"A charming diary of life with a tame magpie-despite George's bad behaviour, [George] will render corvid lovers (like me) green with envy!" -Katherine May, author of Wintering

"Illustrated throughout with pen-and-ink drawings, this charming memoir about the author's accidental adventures in avian rescue offers tantalizing insights into her struggle to fly free of the difficult emotional legacy bequeathed by her literary-icon parents, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. A poignantly heartwarming delight." -Kirkus Reviews

"Lovely. . . In lyrical prose full of introspection and humor, Hughes describes George being washed by her dogs, his learning to fly, and his curiosity about everything. . . Enlivened with Hughes' drawings, this portrait of a bird mirrors how each of us maneuvers through our own existence." -*starred* Booklist

"In this funny, tender memoir, Frieda Hughes casts a brilliant light into her relationship with George, a member of the most beautiful and fascinating of avian species, the magpie. As she shows us the challenges, frustrations, anxieties, love and joy which may be gained by closeness to another being, Hughes perfectly illustrates how our lives may be enriched and expanded by the experience." -Esther Woolfson, author of Corvus

"There is an astringent beauty to Frieda Hughes' George. It's one of those books that appears to be about one thing-in this case, hand-rearing the eponymous orphan magpie-whilst being about something altogether more profound: love, loss and how inextricably linked they are. Love comes alive in Hughes' pages as an act of acute attentiveness. Loss lingers in the margins, but George doesn't baulk at the sha...

"A charming diary of life with a tame magpie-despite George's bad behaviour, [George] will render corvid lovers (like me) green with envy!" -Katherine May, author of Wintering

"Illustrated throughout with pen-and-ink drawings, this charming memoir about the author's accidental adventures in avian rescue offers tantalizing insights into her struggle to fly free of the difficult emotional legacy bequeathed by her literary-icon parents, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. A poignantly heartwarming delight." -Kirkus Reviews

"Lovely. . . In lyrical prose full of introspection and humor, Hughes describes George being washed by her dogs, his learning to fly, and his curiosity about everything. . . Enlivened with Hughes' drawings, this portrait of a bird mirrors how each of us maneuvers through our own existence." -*starred* Booklist

"In this funny, tender memoir, Frieda Hughes casts a brilliant light into her relationship with George, a member of the most beautiful and fascinating of avian species, the magpie. As she shows us the challenges, frustrations, anxieties, love and joy which may be gained by closeness to another being, Hughes perfectly illustrates how our lives may be enriched and expanded by the experience." -Esther Woolfson, author of Corvus

"There is an astringent beauty to Frieda Hughes' George. It's one of those books that appears to be about one thing-in this case, hand-rearing the eponymous orphan magpie-whilst being about something altogether more profound: love, loss and how inextricably linked they are. Love comes alive in Hughes' pages as an act of acute attentiveness. Loss lingers in the margins, but George doesn't baulk at the sha...

Readers Top Reviews

Mikey D

This new work by the poet, artist (and animal rescuer), Frieda Hughes is an absolute delight. This tells the tale of a baby Magpie she discovered in her garden (and almost decapitated whilst gardening). The relationship they formed was truly special. The story is told with love about George the Magpie. And follows the bond formed with her and her three dogs. The many encounters George has with neighbours and various workmen are told with gentle humour and acute observation. This lovely book covers all the travails she experienced in raising this inquisitive and wilful Magpie. The constant crapping on the floor and down the back of her work shirt and, yes, even on the dogs. The stealing of food and the hiding of the same throughout the kitchen. The dog poo being taken from the litter tray and hidden away. George captured her heart just as her marriage was failing. The stress of which was damaging her health (although it was after the break-up that she truly realised this as the primary cause). All of this is captured in heartbreaking detail as a background to the love and affection she shared with George and, perhaps, no longer shared with The Ex (as he is called throughout the book). George's inevitable need to finally break the bonds with Frieda and the protection her home offered, can be seen in parallel with the dissolution of her marriage. But George leads to Oscar 1 and then Oscar 2 (both crows), then ducks and on to Owls. When The Ex goes on holiday to Australia, Frieda decides to finally get her motorbike licence (it takes 3 attempts). This is also her ticket to freedom of a different sort. She tells her story beautifully. She has her home, her garden and her motorbike. And she has her menagerie. And we have 'George, a Magpie Memoir'. The book is also illustrated by the author. Thankyou Frieda Hughes for a brilliant book.

Melanie L.

Such a beautifully told story - almost felt as though I'd gotten to know George. Very much hoping a raven fledgling finds its way to Frieda, that would be a wonderful sequel......

Short Excerpt Teaser

1. May May Saturday 19 May 2007

Working in the garden daily, I noticed a pair of magpies building a huge nest in the neighbour's copper-leafed prunus tree, which rose out of the hedge between our two gardens about 50 yards from the front of my house.

Twig by twisty twig, they knitted this wooden bag for their babies; it hung in the highest of the branches like a dark lantern, a testament to their skill at construction, a very large, twiggy nest, shaped like a tall, inverted pear, with a twiggy lid that was attached by a spine at the back, but sat above the rim to allow parental access from the sides while protecting from the worst of the rain. I'd never seen anything quite like it.

The tree's heavy presence and purple-dark leaves were now made more threatening by the habitation of these magpies and their staccato laughter; their noise sounded as if hard wooden blocks were being thrown at a wall, so they clattered to the ground. Toiling beneath them as I dug narrow trenches for flowerbed edging pavers, and planting hellebores and miniature azaleas, I had the idea that they were the jokers and we humans were their fools.

They screeched and made strange chugging noises; king and queen of the garden, they challenged the wood pigeons and doves and teased the jackdaws and crows without shame. They skipped and flounced and appeared hideously happy as they performed their quick little dance steps, wearing their black-and-white shiny suits with that tinge of oil-slick blue-green like a stain on their inky feathers. Where crows possessed gravitas, jackdaws possessed curiosity, and magpies possessed a tangible sense of humour.

Magpies are vermin, I was told by farmers and friends alike, and anyone who cared to voice an opinion, as if they knew all about magpies. Their seemingly universal verdict sounded trite and rehearsed rather than being a warranted judgement that any one of them had come up with on their own. So, I disagreed with them, but nevertheless, when the twelve wild duck eggs started to vanish from the nest on the island in the middle of the large fishpond I'd constructed, I began to regard the magpie nest with some suspicion.

Every morning I'd find another egg missing, and broken bits of shell littering the pond edge. It seemed the egg-eater was coming for an egg a day. Three eggs into the carnage, the duck stopped sitting and deserted the nest; the eggs continued to disappear until there were none left. It was magpies, someone told me, although in truth it could have been any number of creatures: crows, ravens, ferrets, mink, foxes, rats. Even lovable hedgehogs crave a raw egg and there are several of them in my garden. Jackdaws eat eggs too; sometimes I'd look out of the kitchen window and there would be eight or a dozen of them perched on the table and benches that stood on the bit of grass I called "the front lawn." (I've since turned it into a rockery and series of winding flowerbeds full of low-growing evergreen bushes.)

The jackdaws and crows hung around the front yard like mourners waiting for the funeral in their sooty blacks, but I liked them; they had dignity and poise, unlike the magpies who were imps. If I put bread out for the birds, the big black crows would fly over, their slow, powerful wingbeats bringing them down like burnt-out space junk until they littered the crumbling tarmac of the circular forecourt, where they got on with the business of devouring bread. The jackdaws would step aside for their larger cousins. But the magpies would sidle in, cackling and fizzing, hyper-energetic and focused on food.

The bread had to be brown; I was amused to find that the birds ignored white bread altogether, which festered outside, becoming soggy heaps in the first rain and eventually washing away as a sort of greying, diluting slime. Even the rats and mice weren't interested.

The night before, there had been fierce winds. Inside the house the windows had felt to be shaking free of their box frames, their weights rattling inside their hidden sash-coffins. The large house, beaten by the storm, gave me a sense of being in a ship on a wild sea. Our bedroom on the third floor at the back was like the bridge; looking out over the neighbours and forging a path through the stormy skies. The slimmer trees had leaned and bowed, the bigger ones had lost branches, and now here, when I looked up, was the broken, torn-apart tatter of the magpie twig-nest.

Good, I thought firmly, no more magpie nest meant no more magpie eggs, so fewer magpies to eat duck eggs. Even as the thoughts crossed my mind, I felt a stab of guilt; I'd damned them without evidence, and I've spent so much of my life rescuing wounded birds and...

Working in the garden daily, I noticed a pair of magpies building a huge nest in the neighbour's copper-leafed prunus tree, which rose out of the hedge between our two gardens about 50 yards from the front of my house.

Twig by twisty twig, they knitted this wooden bag for their babies; it hung in the highest of the branches like a dark lantern, a testament to their skill at construction, a very large, twiggy nest, shaped like a tall, inverted pear, with a twiggy lid that was attached by a spine at the back, but sat above the rim to allow parental access from the sides while protecting from the worst of the rain. I'd never seen anything quite like it.

The tree's heavy presence and purple-dark leaves were now made more threatening by the habitation of these magpies and their staccato laughter; their noise sounded as if hard wooden blocks were being thrown at a wall, so they clattered to the ground. Toiling beneath them as I dug narrow trenches for flowerbed edging pavers, and planting hellebores and miniature azaleas, I had the idea that they were the jokers and we humans were their fools.

They screeched and made strange chugging noises; king and queen of the garden, they challenged the wood pigeons and doves and teased the jackdaws and crows without shame. They skipped and flounced and appeared hideously happy as they performed their quick little dance steps, wearing their black-and-white shiny suits with that tinge of oil-slick blue-green like a stain on their inky feathers. Where crows possessed gravitas, jackdaws possessed curiosity, and magpies possessed a tangible sense of humour.

Magpies are vermin, I was told by farmers and friends alike, and anyone who cared to voice an opinion, as if they knew all about magpies. Their seemingly universal verdict sounded trite and rehearsed rather than being a warranted judgement that any one of them had come up with on their own. So, I disagreed with them, but nevertheless, when the twelve wild duck eggs started to vanish from the nest on the island in the middle of the large fishpond I'd constructed, I began to regard the magpie nest with some suspicion.

Every morning I'd find another egg missing, and broken bits of shell littering the pond edge. It seemed the egg-eater was coming for an egg a day. Three eggs into the carnage, the duck stopped sitting and deserted the nest; the eggs continued to disappear until there were none left. It was magpies, someone told me, although in truth it could have been any number of creatures: crows, ravens, ferrets, mink, foxes, rats. Even lovable hedgehogs crave a raw egg and there are several of them in my garden. Jackdaws eat eggs too; sometimes I'd look out of the kitchen window and there would be eight or a dozen of them perched on the table and benches that stood on the bit of grass I called "the front lawn." (I've since turned it into a rockery and series of winding flowerbeds full of low-growing evergreen bushes.)

The jackdaws and crows hung around the front yard like mourners waiting for the funeral in their sooty blacks, but I liked them; they had dignity and poise, unlike the magpies who were imps. If I put bread out for the birds, the big black crows would fly over, their slow, powerful wingbeats bringing them down like burnt-out space junk until they littered the crumbling tarmac of the circular forecourt, where they got on with the business of devouring bread. The jackdaws would step aside for their larger cousins. But the magpies would sidle in, cackling and fizzing, hyper-energetic and focused on food.

The bread had to be brown; I was amused to find that the birds ignored white bread altogether, which festered outside, becoming soggy heaps in the first rain and eventually washing away as a sort of greying, diluting slime. Even the rats and mice weren't interested.

The night before, there had been fierce winds. Inside the house the windows had felt to be shaking free of their box frames, their weights rattling inside their hidden sash-coffins. The large house, beaten by the storm, gave me a sense of being in a ship on a wild sea. Our bedroom on the third floor at the back was like the bridge; looking out over the neighbours and forging a path through the stormy skies. The slimmer trees had leaned and bowed, the bigger ones had lost branches, and now here, when I looked up, was the broken, torn-apart tatter of the magpie twig-nest.

Good, I thought firmly, no more magpie nest meant no more magpie eggs, so fewer magpies to eat duck eggs. Even as the thoughts crossed my mind, I felt a stab of guilt; I'd damned them without evidence, and I've spent so much of my life rescuing wounded birds and...