Americas

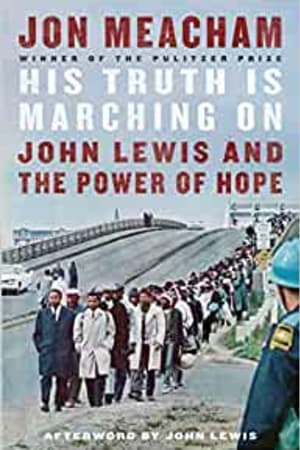

- Publisher : Random House; Illustrated edition

- Published : 25 Aug 2020

- Pages : 368

- ISBN-10 : 1984855026

- ISBN-13 : 9781984855022

- Language : English

His Truth Is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope

#1 NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • An intimate and revealing portrait of civil rights icon and longtime U.S. congressman John Lewis, linking his life to the painful quest for justice in America from the 1950s to the present-from the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Soul of America

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY THE WASHINGTON POST AND COSMOPOLITAN

John Lewis, who at age twenty-five marched in Selma, Alabama, and was beaten on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, was a visionary and a man of faith. Drawing on decades of wide-ranging interviews with Lewis, Jon Meacham writes of how this great-grandson of a slave and son of an Alabama tenant farmer was inspired by the Bible and his teachers in nonviolence, Reverend James Lawson and Martin Luther King, Jr., to put his life on the line in the service of what Abraham Lincoln called "the better angels of our nature." From an early age, Lewis learned that nonviolence was not only a tactic but a philosophy, a biblical imperative, and a transforming reality. At the age of four, Lewis, ambitious to become a minister, practiced by preaching to his family's chickens. When his mother cooked one of the chickens, the boy refused to eat it-his first act, he wryly recalled, of nonviolent protest. Integral to Lewis's commitment to bettering the nation was his faith in humanity and in God-and an unshakable belief in the power of hope.

Meacham calls Lewis "as important to the founding of a modern and multiethnic twentieth- and twenty-first-century America as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison and Samuel Adams were to the initial creation of the Republic itself in the eighteenth century." A believer in the injunction that one should love one's neighbor as oneself, Lewis was arguably a saint in our time, risking limb and life to bear witness for the powerless in the face of the powerful. In many ways he brought a still-evolving nation closer to realizing its ideals, and his story offers inspiration and illumination for Americans today who are working for social and political change.

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY THE WASHINGTON POST AND COSMOPOLITAN

John Lewis, who at age twenty-five marched in Selma, Alabama, and was beaten on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, was a visionary and a man of faith. Drawing on decades of wide-ranging interviews with Lewis, Jon Meacham writes of how this great-grandson of a slave and son of an Alabama tenant farmer was inspired by the Bible and his teachers in nonviolence, Reverend James Lawson and Martin Luther King, Jr., to put his life on the line in the service of what Abraham Lincoln called "the better angels of our nature." From an early age, Lewis learned that nonviolence was not only a tactic but a philosophy, a biblical imperative, and a transforming reality. At the age of four, Lewis, ambitious to become a minister, practiced by preaching to his family's chickens. When his mother cooked one of the chickens, the boy refused to eat it-his first act, he wryly recalled, of nonviolent protest. Integral to Lewis's commitment to bettering the nation was his faith in humanity and in God-and an unshakable belief in the power of hope.

Meacham calls Lewis "as important to the founding of a modern and multiethnic twentieth- and twenty-first-century America as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison and Samuel Adams were to the initial creation of the Republic itself in the eighteenth century." A believer in the injunction that one should love one's neighbor as oneself, Lewis was arguably a saint in our time, risking limb and life to bear witness for the powerless in the face of the powerful. In many ways he brought a still-evolving nation closer to realizing its ideals, and his story offers inspiration and illumination for Americans today who are working for social and political change.

Editorial Reviews

Chapter One

A Hard Life, a Serious Life

Troy, Alabama: Beginnings to 1957

Work and put your trust in God, and God's gonna take care of his children. God's gonna take care of his children.

-Oft-repeated counsel from Willie Mae Carter Lewis, John's mother

Costly grace . . . is costly because it costs a man his life, and it is grace because it gives a man the only true life.

-Dietrich Bonhoeffer

For John Lewis, slavery wasn't an abstraction. It was as real to him as his great-grandfather, Frank Carter, who lived until his great-grandson was seven. Light-skinned, hardworking, and self-confident, Carter, whom Lewis called "Grandpapa," had been born into enslavement in Pike County, Alabama, in 1862. The family has long believed that a white man was likely Frank Carter's father-Carter and his own son, whose name was Dink, were, Lewis recalled, "light, very fair, and their hair was different, what we could call good hair"-but the subject was shrouded in secrecy and silence. This much is clear: The trajectory of the infant Frank Carter's life was fundamentally changed on Thursday, January 1, 1863, when President Lincoln declared the enslaved in the seceded Confederate States of America were now free, and by the ratification, in December 1865, of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery "within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

Coming of age in Reconstruction and under Jim Crow, Carter was driven and skilled in the world available to him. Yet the "new birth of freedom" of which Lincoln had spoken at Gettysburg in 1863 had failed to come fully into being after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox in 1865. Within eight months of the war's end, Alabama's legislature had instituted a Black Code to curtail the rights of African Americans and give the old ways new form and new force. In 1866, the federal government, driven by Republicans in Congress, sought to bring interracial democracy to the South. The reactionary Black Code was repealed; new constitutions were written; black people were by and large allowed to vote; and African American candidates were elected to federal, state, and local office.

White reaction was fierce. The Ku Klux Klan was founded in these postbellum years-a Confederate general named Edmund Pettus was a grand dragon-and, by 1901, when Frank Carter was nearly forty, white Alabama had reverted as much as it could to an antebellum order by legalizing segregation, circumscribing suffrage, and banning interracial marriage. At the dawn of a new century, then, the old color line had been redrawn and reinforced.

Alabama's 1901 constitution establishing white supremacy had been debated in Montgomery from May to September of that year, en...

A Hard Life, a Serious Life

Troy, Alabama: Beginnings to 1957

Work and put your trust in God, and God's gonna take care of his children. God's gonna take care of his children.

-Oft-repeated counsel from Willie Mae Carter Lewis, John's mother

Costly grace . . . is costly because it costs a man his life, and it is grace because it gives a man the only true life.

-Dietrich Bonhoeffer

For John Lewis, slavery wasn't an abstraction. It was as real to him as his great-grandfather, Frank Carter, who lived until his great-grandson was seven. Light-skinned, hardworking, and self-confident, Carter, whom Lewis called "Grandpapa," had been born into enslavement in Pike County, Alabama, in 1862. The family has long believed that a white man was likely Frank Carter's father-Carter and his own son, whose name was Dink, were, Lewis recalled, "light, very fair, and their hair was different, what we could call good hair"-but the subject was shrouded in secrecy and silence. This much is clear: The trajectory of the infant Frank Carter's life was fundamentally changed on Thursday, January 1, 1863, when President Lincoln declared the enslaved in the seceded Confederate States of America were now free, and by the ratification, in December 1865, of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery "within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

Coming of age in Reconstruction and under Jim Crow, Carter was driven and skilled in the world available to him. Yet the "new birth of freedom" of which Lincoln had spoken at Gettysburg in 1863 had failed to come fully into being after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox in 1865. Within eight months of the war's end, Alabama's legislature had instituted a Black Code to curtail the rights of African Americans and give the old ways new form and new force. In 1866, the federal government, driven by Republicans in Congress, sought to bring interracial democracy to the South. The reactionary Black Code was repealed; new constitutions were written; black people were by and large allowed to vote; and African American candidates were elected to federal, state, and local office.

White reaction was fierce. The Ku Klux Klan was founded in these postbellum years-a Confederate general named Edmund Pettus was a grand dragon-and, by 1901, when Frank Carter was nearly forty, white Alabama had reverted as much as it could to an antebellum order by legalizing segregation, circumscribing suffrage, and banning interracial marriage. At the dawn of a new century, then, the old color line had been redrawn and reinforced.

Alabama's 1901 constitution establishing white supremacy had been debated in Montgomery from May to September of that year, en...

Readers Top Reviews

David CastaldoAlan G

An absolute brilliant read. Jon Meacham does an wonderful job of bringing this amazing life of John Lewis to us. Front cover to cover you will take a journey like no other. A book that should be in every high school as part of their history class. This book is worth your time.

GJB

I have read many books on this period of history and John Lewis should rank alongside MLK. This is well written so that even a casual observe can get benefits from reading. I think Jon Meacham really brings great feeling for the intensity John Lewis brought to the Movement and shares his love of people. The humanity of John Lewis is really brought to the fore and while he wouldn’t say he was a saint at the present time he was most probably as near as anybody. Excellent book worked well with additions from Mr Lewis and definitely brings out the respect from both parties.

Scott J Pearson

The recently deceased congressman John Lewis has been a public light to the United States for over fifty years. Nicknamed “the conscience of Congress,” he courageously campaigned for civil rights since a college student in Nashville. The author Jon Meacham, surely one of America’s greatest biographers, writes this history of Lewis’ doings in the 1960s. With extreme acuity, gravity, and imagery, he captures what the civil rights movement resembled on the inside. In so doing, he memorializes Lewis in a way that proudly continues Lewis’ unique legacy. I can compare reading the early chapters of this book to only one life experience – a tour of the Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee. I was emotionally overwhelmed and captivated by the national struggle to love all races. Meacham’s research and writing so excels that he makes us see the world through Lewis’ eyes. And of course, Lewis’ vision of the world, captured in Dr. King’s phrase “the beloved community,” was and is one that ought to be held onto. Lewis and others had to endure much to receive their just place in American culture. Regardless of one’s politics, ethnicity, or nationality, this story needs to be retold again and again. Lewis’ particular tale is one of courage, suffering, and eventual triumph. He famously even had his skull cracked by police in Selma, Alabama, as a testimony that black lives count for something. A photograph of him seeing recent Black Lives Matter protests precedes an afterword in the book by Lewis himself. The main weakness of this book lies in its brevity. It only recounts about a decade of drama in Lewis’ life. I am left wanting to know this great human more. I am left wanting to learn about how he implemented his vision in one of the most difficult of all places – the United States Congress. I am left wanting to hear about his gentility as he transformed from a civil-rights soldier to dignified leader, much in the way that Washington, Grant, and Eisenhower have. Lewis’ greatness is not restricted to reactions to his skin color in the 1960s American South; it spans to his universal vision for the world. Meacham leaves us with an epilogue that describes such – again, I want more. In an age of partisanship and vacuous national leadership, I hope that many read this work. It’s not inspiring. It’s tragic and sad, even disheartening. How can fellow human beings treat each other so poorly? This work corrects such prejudices and expresses deep determination to fight for what’s right and good and, dare I say, holy in this world. In the process of reading, it made me examine my own conscience and place in this world. Like all good expressions of the human spirit, it leaves me just wanting more.

Karen

His Truth Is Marching on: John Lewis and the Power of Hope is the new release by Jon Meacham. I always look forward to any book written by Jon Meacham, but this one was difficult to read with the recent passing of Congressman John Lewis. We all know of John Lewis from his time in Congress, as well as that horrific day in Selma known as Bloody Sunday. However, most people do not know the true life of John Lewis...those moments in his life that were not a headline on the news. Jon Meacham gives us those moments throughout the pages of this book...from the humble beginnings as a child to the years of activism...John Meacham eloquently tells the story of a true icon and American hero. This is a book rich in history, and one that everyone should read. John Lewis lead by example, and fought every day of his life for what he believed in. He has never let anyone or anything stop his voice from being heard. This books shows how far we have come as a country, but it also shows how much more work needs to be done in order for us to achieve the one thing John Lewis fought for his entire life...equal rights for every single person. John Lewis once said, "Do not get lost in a sea of despair. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Our struggle is not the struggle of a day, a week, a month, or a year, it is the struggle of a lifetime. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble." These are simple but yet extremely powerful words we should all live by, especially when so much injustice continues to happen every day. I would like to thank Jon Meacham, Random House Publishing Group-Random House and NetGalley for allowing me the opportunity to read and review an advance reader copy of this book. My views are my own, and are in no way influenced by anyone else.

Robyn

This is what I needed to read right now in this time of racial turmoil. Meacham's ability to discuss Lewis's faith intertwined with an obvious deep understanding of scripture is straight forward and non preachy. This is the first time I have had a sense of peace in months and remembering the wonderful people in the early movement felt like spending time with old friends...friends I shed blood with in the 60s. I still believe in the Beloved Community and it was nice to spend the time remembering why we fought for it.

Short Excerpt Teaser

Chapter One

A Hard Life, a Serious Life

Troy, Alabama: Beginnings to 1957

Work and put your trust in God, and God's gonna take care of his children. God's gonna take care of his children.

-Oft-repeated counsel from Willie Mae Carter Lewis, John's mother

Costly grace . . . is costly because it costs a man his life, and it is grace because it gives a man the only true life.

-Dietrich Bonhoeffer

For John Lewis, slavery wasn't an abstraction. It was as real to him as his great-grandfather, Frank Carter, who lived until his great-grandson was seven. Light-skinned, hardworking, and self-confident, Carter, whom Lewis called "Grandpapa," had been born into enslavement in Pike County, Alabama, in 1862. The family has long believed that a white man was likely Frank Carter's father-Carter and his own son, whose name was Dink, were, Lewis recalled, "light, very fair, and their hair was different, what we could call good hair"-but the subject was shrouded in secrecy and silence. This much is clear: The trajectory of the infant Frank Carter's life was fundamentally changed on Thursday, January 1, 1863, when President Lincoln declared the enslaved in the seceded Confederate States of America were now free, and by the ratification, in December 1865, of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery "within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

Coming of age in Reconstruction and under Jim Crow, Carter was driven and skilled in the world available to him. Yet the "new birth of freedom" of which Lincoln had spoken at Gettysburg in 1863 had failed to come fully into being after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox in 1865. Within eight months of the war's end, Alabama's legislature had instituted a Black Code to curtail the rights of African Americans and give the old ways new form and new force. In 1866, the federal government, driven by Republicans in Congress, sought to bring interracial democracy to the South. The reactionary Black Code was repealed; new constitutions were written; black people were by and large allowed to vote; and African American candidates were elected to federal, state, and local office.

White reaction was fierce. The Ku Klux Klan was founded in these postbellum years-a Confederate general named Edmund Pettus was a grand dragon-and, by 1901, when Frank Carter was nearly forty, white Alabama had reverted as much as it could to an antebellum order by legalizing segregation, circumscribing suffrage, and banning interracial marriage. At the dawn of a new century, then, the old color line had been redrawn and reinforced.

Alabama's 1901 constitution establishing white supremacy had been debated in Montgomery from May to September of that year, ending in time for the cotton harvest. Fifty miles away from the state capitol, Frank Carter leased his land from J. S. "Big Josh" Copeland, a major figure in Troy, the Pike County seat. Carter worked his way to an unusual level of sharecropping called "standing rent," which meant he paid Copeland to lease the land but did not owe the landlord any of his yield beyond the rent. Diligent, resourceful, and determined, Lewis's great-grandfather did the best he could under the constraints of his time. "He couldn't read or write," his great-grandson said, "but he could do financial transactions in his head faster than the man on the other side of the desk could work them out with a pen and paper." Carter took great pride in just about everything he did. "He would sit in his rocking chair on his porch," John Lewis recalled, "and he acted like he was the king."

In a way, he was-at least of the piece of Pike County that came to be known as Carter's Quarters. It was there, in 1914, that his granddaughter Willie Mae was born to Frank's son Dink. In 1932, she married Edward Lewis, who had been born (along with his twin sister, Edna) in 1909 in Roberta, Georgia. Eddie's mother, Lula, had come to Carter's Quarters after a separation from her husband, Henry. Willie Mae and Eddie met at Macedonia Baptist Church and fell in love. He called her "Sugarfoot"; she called him "Shorty."

They were to have ten children: Ora, Edward, Sammy, Grant, Freddie, Adolph, William, Ethel, Rosa (also called Mae)-and John Robert Lewis, who was born in a shotgun shack in Carter's Quarters on a cold Wednesday, February 21, 1940. Readers of The Montgomery Advertiser that day saw headlines about the German sinking of three British ships and Democratic anxiety about President Franklin D. Roosevelt's silence on whether he'd seek a third term. Closer to home, The Troy Messenger reported on a local man's suicide-he had jumped from the nineteenth floor of a downtown Montgomery hotel-and announced an...

A Hard Life, a Serious Life

Troy, Alabama: Beginnings to 1957

Work and put your trust in God, and God's gonna take care of his children. God's gonna take care of his children.

-Oft-repeated counsel from Willie Mae Carter Lewis, John's mother

Costly grace . . . is costly because it costs a man his life, and it is grace because it gives a man the only true life.

-Dietrich Bonhoeffer

For John Lewis, slavery wasn't an abstraction. It was as real to him as his great-grandfather, Frank Carter, who lived until his great-grandson was seven. Light-skinned, hardworking, and self-confident, Carter, whom Lewis called "Grandpapa," had been born into enslavement in Pike County, Alabama, in 1862. The family has long believed that a white man was likely Frank Carter's father-Carter and his own son, whose name was Dink, were, Lewis recalled, "light, very fair, and their hair was different, what we could call good hair"-but the subject was shrouded in secrecy and silence. This much is clear: The trajectory of the infant Frank Carter's life was fundamentally changed on Thursday, January 1, 1863, when President Lincoln declared the enslaved in the seceded Confederate States of America were now free, and by the ratification, in December 1865, of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery "within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

Coming of age in Reconstruction and under Jim Crow, Carter was driven and skilled in the world available to him. Yet the "new birth of freedom" of which Lincoln had spoken at Gettysburg in 1863 had failed to come fully into being after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox in 1865. Within eight months of the war's end, Alabama's legislature had instituted a Black Code to curtail the rights of African Americans and give the old ways new form and new force. In 1866, the federal government, driven by Republicans in Congress, sought to bring interracial democracy to the South. The reactionary Black Code was repealed; new constitutions were written; black people were by and large allowed to vote; and African American candidates were elected to federal, state, and local office.

White reaction was fierce. The Ku Klux Klan was founded in these postbellum years-a Confederate general named Edmund Pettus was a grand dragon-and, by 1901, when Frank Carter was nearly forty, white Alabama had reverted as much as it could to an antebellum order by legalizing segregation, circumscribing suffrage, and banning interracial marriage. At the dawn of a new century, then, the old color line had been redrawn and reinforced.

Alabama's 1901 constitution establishing white supremacy had been debated in Montgomery from May to September of that year, ending in time for the cotton harvest. Fifty miles away from the state capitol, Frank Carter leased his land from J. S. "Big Josh" Copeland, a major figure in Troy, the Pike County seat. Carter worked his way to an unusual level of sharecropping called "standing rent," which meant he paid Copeland to lease the land but did not owe the landlord any of his yield beyond the rent. Diligent, resourceful, and determined, Lewis's great-grandfather did the best he could under the constraints of his time. "He couldn't read or write," his great-grandson said, "but he could do financial transactions in his head faster than the man on the other side of the desk could work them out with a pen and paper." Carter took great pride in just about everything he did. "He would sit in his rocking chair on his porch," John Lewis recalled, "and he acted like he was the king."

In a way, he was-at least of the piece of Pike County that came to be known as Carter's Quarters. It was there, in 1914, that his granddaughter Willie Mae was born to Frank's son Dink. In 1932, she married Edward Lewis, who had been born (along with his twin sister, Edna) in 1909 in Roberta, Georgia. Eddie's mother, Lula, had come to Carter's Quarters after a separation from her husband, Henry. Willie Mae and Eddie met at Macedonia Baptist Church and fell in love. He called her "Sugarfoot"; she called him "Shorty."

They were to have ten children: Ora, Edward, Sammy, Grant, Freddie, Adolph, William, Ethel, Rosa (also called Mae)-and John Robert Lewis, who was born in a shotgun shack in Carter's Quarters on a cold Wednesday, February 21, 1940. Readers of The Montgomery Advertiser that day saw headlines about the German sinking of three British ships and Democratic anxiety about President Franklin D. Roosevelt's silence on whether he'd seek a third term. Closer to home, The Troy Messenger reported on a local man's suicide-he had jumped from the nineteenth floor of a downtown Montgomery hotel-and announced an...