Politics & Government

- Publisher : Dial Press Trade Paperback

- Published : 13 Sep 2022

- Pages : 416

- ISBN-10 : 0525512454

- ISBN-13 : 9780525512455

- Language : English

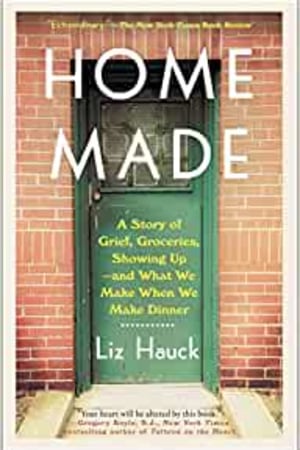

Home Made: A Story of Grief, Groceries, Showing Up--and What We Make When We Make Dinner

NEW YORK TIMES EDITORS' CHOICE • An "extraordinary" (The New York Times Book Review) tender and vivid memoir about the radical grace we discover when we consider ourselves bound together in community, and a moving account of one woman's attempt to answer the essential question Who are we to one another?

"Your heart will be altered by this book."-Gregory Boyle, S.J., New York Times bestselling author of Tattoos on the Heart

Liz Hauck and her dad had a plan to start a weekly cooking program in a residential home for teenage boys in state care, which was run by the human services agency he co-directed. When her father died before they had a chance to get the project started, Liz decided she would try it without him. She didn't know what to expect from volunteering with court-involved youth, but as a high school teacher she knew that teenagers are drawn to food-related activities, and as a daughter, she believed that if she and the kids made even a single dinner together she could check one box off her father's long, unfinished to-do list. This is the story of what happened around the table, and how one dinner became one hundred dinners.

"The kids picked the menus, I bought the groceries," Liz writes, "and we cooked and ate dinner together for two hours a week for nearly three years. Sometimes improvisation in kitchens is disastrous. But sometimes, a combination of elements produces something spectacularly unexpected. I think that's why, when we don't know what else to do, we feed our neighbors."

Capturing the clumsy choreography of cooking with other people, this is a sharply observed story about the ways we behave when we are hungry and the conversations that happen at the intersections of flavor and memory, vulnerability and strength, grief and connection.

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY SHE READS

"Your heart will be altered by this book."-Gregory Boyle, S.J., New York Times bestselling author of Tattoos on the Heart

Liz Hauck and her dad had a plan to start a weekly cooking program in a residential home for teenage boys in state care, which was run by the human services agency he co-directed. When her father died before they had a chance to get the project started, Liz decided she would try it without him. She didn't know what to expect from volunteering with court-involved youth, but as a high school teacher she knew that teenagers are drawn to food-related activities, and as a daughter, she believed that if she and the kids made even a single dinner together she could check one box off her father's long, unfinished to-do list. This is the story of what happened around the table, and how one dinner became one hundred dinners.

"The kids picked the menus, I bought the groceries," Liz writes, "and we cooked and ate dinner together for two hours a week for nearly three years. Sometimes improvisation in kitchens is disastrous. But sometimes, a combination of elements produces something spectacularly unexpected. I think that's why, when we don't know what else to do, we feed our neighbors."

Capturing the clumsy choreography of cooking with other people, this is a sharply observed story about the ways we behave when we are hungry and the conversations that happen at the intersections of flavor and memory, vulnerability and strength, grief and connection.

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY SHE READS

Editorial Reviews

"[Home Made] is flawless. . . . It's a true story about boys who got the short end of the stick through no fault of their own, inequality the most destructive and most indestructible monster of them all."-The Boston Globe

"Because [Liz Hauck] writes with such unvarnished clarity and pragmatism, sudden moments of tenderness burst open on the page. . . . It turns out that showing up to cook and eat with people once a week allows for startlingly deep moments of connection and community. That's all that happens. And it's extraordinary."-Kate Christensen, The New York Times Book Review

"Liz Hauck reveals fascinating, sobering, and urgent truths about boyhood, inequality, and the power and promise of community."-Piper Kerman, New York Times bestselling author of Orange Is the New Black

"I could not wait to get home each night so I could get back to reading Home Made. I cared so much about everybody in it. Hauck's writing embodies what she knows about successful volunteering: Show up on time when you said you would, do what you said you would do, and leave. I loved this book so much. I stayed up way later than I should have to just get one more chapter in before sleeping."-Gabrielle Hamilton, New York Times bestselling author of Blood, Bones & Butter

"At every turn in Home Made, Liz Hauck suggests that we all ought to build a longer table, instead of a higher wall. With grace and tenderness, this memoir utterly affirms that it is the relationship that heals. Food brings us to the table, but cherishing leads us to joy and bravery. This is an important book because it reminds us not to venture to the margins to make a difference, but to allow the folks there to make us different. Your heart will be altered by this book."-Gregory Boyle, S.J., New York Times bestselling author of Tattoos on the Heart and founder of Homeboy Industries

"Wise and empathetic, Liz Hauck describes the process of ...

"Because [Liz Hauck] writes with such unvarnished clarity and pragmatism, sudden moments of tenderness burst open on the page. . . . It turns out that showing up to cook and eat with people once a week allows for startlingly deep moments of connection and community. That's all that happens. And it's extraordinary."-Kate Christensen, The New York Times Book Review

"Liz Hauck reveals fascinating, sobering, and urgent truths about boyhood, inequality, and the power and promise of community."-Piper Kerman, New York Times bestselling author of Orange Is the New Black

"I could not wait to get home each night so I could get back to reading Home Made. I cared so much about everybody in it. Hauck's writing embodies what she knows about successful volunteering: Show up on time when you said you would, do what you said you would do, and leave. I loved this book so much. I stayed up way later than I should have to just get one more chapter in before sleeping."-Gabrielle Hamilton, New York Times bestselling author of Blood, Bones & Butter

"At every turn in Home Made, Liz Hauck suggests that we all ought to build a longer table, instead of a higher wall. With grace and tenderness, this memoir utterly affirms that it is the relationship that heals. Food brings us to the table, but cherishing leads us to joy and bravery. This is an important book because it reminds us not to venture to the margins to make a difference, but to allow the folks there to make us different. Your heart will be altered by this book."-Gregory Boyle, S.J., New York Times bestselling author of Tattoos on the Heart and founder of Homeboy Industries

"Wise and empathetic, Liz Hauck describes the process of ...

Readers Top Reviews

Laura A.William M

I was drawn in by the prologue, as Hauck remembered her own Saturday morning breakfasts growing up and laid the foundation for this project she had planned out with her dad – one that involved his 'other kids' in a group home that he cofounded, that taught the boys something about cooking and community but taught her more than she could have ever imagined, a project that her dad died too soon to see realized… As a teacher myself, Hauck’s initial read of the boys felt so familiar – I love how she stuck it out with the project and shared this glimpse into the lives of these kids that we so rarely have a chance to connect with on a sub-surface level. Hauck beautifully recounts her time spent in the kitchen and at the table with the boys, and her own struggles with grief and finding her purpose… You won’t want to put this book down!

SusieQLaura A.Wil

Better than a new silk tie, a box of favorite chocolates, or a coffee mug inscribed with “World’s Best Dad” HOME MADE is the perfect Father’s Day gift a girl could give her Dad, I loved it! Started on Friday, finished on Sunday, I wanted to ( had to!) keep reading, What dinner did they make that week? Who was there? Who went AWOL? Who helped? Who just came to eat? It was not just the food. It was the personalities, the problems (How do you cut up chicken with a plastic knife? Where are the pots and pans? Why are the cupboards locked up? What do I do about the guy who can’t read?) I felt the boys’ pain, Liz’s too, their initial distrust of a White teacher, watched their eventual acceptance, mostly, smiled at the names they had for Liz. I wanted to stay for the end of the story, hoping it would be like a gift wrapped up in shiny paper with a big, red bow! Spoiler Alert! Maybe yes, maybe no. You will have to see for yourselves, dear readers. You will be so glad you did. Liz Hauck has honored her father with the perfect present. And the bow is a big one.

Cameron DrydenSus

Where to start? So many emotions… Home Made is the firsthand account of a young woman’s grief at losing her dad—himself founder of a group home and a food lover—to her living tribute to his memory. She cooks and eats a hundred dinners with an ever-changing cast of troubled boys. Often funny, tender, poignant, and sometimes tragic, the book is one of the best windows I’ve ever had into the children’s many disappointments, bravado, humor, coping mechanisms, and how she and they become a family. The dialogue is so authentic, I felt plopped into their kitchen and dining rooms. Liz Hauck is remarkably self-aware and candid about her cluelessness of their world and lets the boys school her. She perseveres to help them cook meals funded with her own meager budget, serving up love with every conversation, interaction, meal, and dessert. Never have I read such an insightful, even-handed view of both sides of the socioeconomic divide. Though favorably reviewed by the New York Times, this debut novel is flying under most people’s radar. I believe Home Made will come to be recognized as one of the most significant stories of its kind. Highly recommended for volunteers, teachers, case & social workers, and everyone who wants to understand and guide troubled youth.

SOttoCameron Dryd

Liz Hauck’s “Home Made” is a story many things all at once: a daughter grieving, a woman searching for her place, and a teacher who visits a boys’ home once a week to cook with them. The memoir’s greatest strength is its ability to characterize with very few details. The boys Hauck cooks with are guarded and don’t want to reveal themselves, but she sees them as clearly as though they were family. At first glance, I was worried “Home Made” would be just another “white savior” narrative (a la Freedom Writers, and the like) but what emerges is actually something more hopeless (and that’s a good thing). Hauck forces the reader to examine the state care system these boys are involved with, putting under scrutiny all the shortcomings of the way we care for kids in need. She does not shy away from the bleakness the boys’ futures hold and their acceptance of it. They have regular run ins with drugs, abuse, crime, prejudice, imprisonment, illness, and death. There are no puppies, rainbows, or butterflies here. That’s the truth. “Home Made” by Liz Hauck serves the highest purpose of memoir: to gaze upon the bleakest views of our world and find equal value in the beauty and the pain.

G.R. KearneySOtto

In full disclosure, I know Liz. We are friends and we taught together in Chicago many years ago. I, too, am a writer. I bought Liz’s book for all of the above reasons and I knew I would read enough of it to be able to send her a note with some direct references to people in the book. I did not expect to become totally engrossed. I couldn’t put HOME MADE down. It is a a great story. It’s a great tribute to Liz’s dad (a man who spent his entire professional life helping to provide care to young people who weren’t able to live with their families and who refused air conditioning in his office for decades until the organization had enough money to air condition the homes the young people lived in). It’s a testament to what a special person Liz is and highlights just a little bit of the wonderful work she has done in so many places to make the world slightly better. Above all, though, it’s a great read. It may seem hard to believe that a story about a young woman trying to find her way and cooking dinner in a group home for boys could be gripping… but it’s exactly that. And it has certainly challenged me to think about whether or not I am doing enough to to make my little corner of the world at least slightly better. I can’t recommend HOME MADE highly enough.

Short Excerpt Teaser

Getting Started

The House is a two-story redbrick building, like the one the Big Bad Wolf couldn't blow down. It sits on a busy city corner, across from a funeral home on one side and an animal shelter on the other. One half mile to the left of it live some of the poorest people in the city of Boston; one half mile to the right live some of the richest. Gerry calls this the world's longest socioeconomic mile, and he says that there are strategy and symbolism in his having chosen this location for the headquarters of his agency. The doors, porch, and shutters that frame each window are painted a bright, flat Crayola green. There's usually graffiti to the left or right of the back door, which was rarely locked during daylight hours. The stairs leading up from the street make an aching sound when you walk on them; covered in carpeting the same gray as the sidewalk outside, they connect the building's two floors. The agency offices were located on the first, and one of the residences the agency ran for youth in state care was on the second, before everything changed. The residence upstairs from my dad's office was one of the boys' programs. At a given time, it housed up to eight of the agency's adolescent clients age fourteen to nineteen who were designated wards of the state, referred through other human service agencies, often after removal from their homes, failed placements with foster families, or short stays in juvenile detention facilities. For them, the House was a temporary group home placement, or at least somewhere to sleep and eat. It used to seem to me that upstairs and downstairs were two clearly divided worlds. Whenever I was at the House as a kid, it was to wait for my father, for a ride home. I'd sit in the waiting room on the couch, which was beige, the way that things that could be anybody's things are beige. Sometimes I would hear raised voices, or the thud of a basketball being dribbled hard against the other side of the ceiling. But for the first twenty-six years of my life, I never went upstairs.

I went to the House to speak to Gerry a few days after receiving his voicemail. Ostensibly, I wanted to discuss the meeting he had scheduled for me with the residents. But really, this visit was a kind of dry run; I didn't want my first time back in the House after my father's death to be the night I met the kids. I didn't know how it would feel to be there without my father, and I didn't want to be messy; I knew I was already fighting other stereotypes. What would the boys think of me, or think I was trying to be? I took a deep breath before going in, noticing the veins in the late-September leaves on the tree between the House and the street, gilded in a final jolt of beauty before their inevitable fall. I pressed my hand against the familiar green door and it was open, so I went inside.

I walked up to the first-floor landing and turned the worn brass knob on the door that led to the office, like I had so many afternoons before. Inside, it looked and smelled the same: the walls, the floor, the stale coffee from that morning still in the coffeepot, the stack of magazines by the entryway. Gerry hadn't changed anything in the building since my father's last day, except for the ceiling, which he reluctantly allowed to be patched when someone warned him that if he didn't, it would fall in.

I made my way to the administrative coordinator's desk and told her I was there to talk to Gerry. My heart pounded. I stared at the typewriter as it sat in the front office. I remembered my dad at that exact typewriter: the mechanical clink as he filled in forms and typed up budgets, the tink-tink of each letter being hit, the clack and whoosh at the end of a line. His exasperated "Shit!" and slow plack-plack of backspacing. I could almost see his solid frame hunched over the outdated machine, glasses perched on his nose, bushy eyebrows furrowed in thought, hands moving slowly over the keys, silk tie thrown over his shoulder to save it from getting sucked in.

"I know, you'd think since we have computers, we could just get rid of that thing," the administrative coordinator said. "But Gerry won't let me. It's kind of ridiculous. You must be Liz."

I averted my eyes from the doorway to what had been my father's office, across the hall. I didn't want to see the pastel drawing of the House that he had commissioned by a local artist, or his chair or books or phone. Especially his phone. That phone looked ugly, plastic, and nondescript. But his for years, it had the patina of the diminishing supply of things he had touched.

I asked the administrative coordinator if she thought a cooking program might work upstairs.

"I don't really know," she said, smiling politely.

<...

The House is a two-story redbrick building, like the one the Big Bad Wolf couldn't blow down. It sits on a busy city corner, across from a funeral home on one side and an animal shelter on the other. One half mile to the left of it live some of the poorest people in the city of Boston; one half mile to the right live some of the richest. Gerry calls this the world's longest socioeconomic mile, and he says that there are strategy and symbolism in his having chosen this location for the headquarters of his agency. The doors, porch, and shutters that frame each window are painted a bright, flat Crayola green. There's usually graffiti to the left or right of the back door, which was rarely locked during daylight hours. The stairs leading up from the street make an aching sound when you walk on them; covered in carpeting the same gray as the sidewalk outside, they connect the building's two floors. The agency offices were located on the first, and one of the residences the agency ran for youth in state care was on the second, before everything changed. The residence upstairs from my dad's office was one of the boys' programs. At a given time, it housed up to eight of the agency's adolescent clients age fourteen to nineteen who were designated wards of the state, referred through other human service agencies, often after removal from their homes, failed placements with foster families, or short stays in juvenile detention facilities. For them, the House was a temporary group home placement, or at least somewhere to sleep and eat. It used to seem to me that upstairs and downstairs were two clearly divided worlds. Whenever I was at the House as a kid, it was to wait for my father, for a ride home. I'd sit in the waiting room on the couch, which was beige, the way that things that could be anybody's things are beige. Sometimes I would hear raised voices, or the thud of a basketball being dribbled hard against the other side of the ceiling. But for the first twenty-six years of my life, I never went upstairs.

I went to the House to speak to Gerry a few days after receiving his voicemail. Ostensibly, I wanted to discuss the meeting he had scheduled for me with the residents. But really, this visit was a kind of dry run; I didn't want my first time back in the House after my father's death to be the night I met the kids. I didn't know how it would feel to be there without my father, and I didn't want to be messy; I knew I was already fighting other stereotypes. What would the boys think of me, or think I was trying to be? I took a deep breath before going in, noticing the veins in the late-September leaves on the tree between the House and the street, gilded in a final jolt of beauty before their inevitable fall. I pressed my hand against the familiar green door and it was open, so I went inside.

I walked up to the first-floor landing and turned the worn brass knob on the door that led to the office, like I had so many afternoons before. Inside, it looked and smelled the same: the walls, the floor, the stale coffee from that morning still in the coffeepot, the stack of magazines by the entryway. Gerry hadn't changed anything in the building since my father's last day, except for the ceiling, which he reluctantly allowed to be patched when someone warned him that if he didn't, it would fall in.

I made my way to the administrative coordinator's desk and told her I was there to talk to Gerry. My heart pounded. I stared at the typewriter as it sat in the front office. I remembered my dad at that exact typewriter: the mechanical clink as he filled in forms and typed up budgets, the tink-tink of each letter being hit, the clack and whoosh at the end of a line. His exasperated "Shit!" and slow plack-plack of backspacing. I could almost see his solid frame hunched over the outdated machine, glasses perched on his nose, bushy eyebrows furrowed in thought, hands moving slowly over the keys, silk tie thrown over his shoulder to save it from getting sucked in.

"I know, you'd think since we have computers, we could just get rid of that thing," the administrative coordinator said. "But Gerry won't let me. It's kind of ridiculous. You must be Liz."

I averted my eyes from the doorway to what had been my father's office, across the hall. I didn't want to see the pastel drawing of the House that he had commissioned by a local artist, or his chair or books or phone. Especially his phone. That phone looked ugly, plastic, and nondescript. But his for years, it had the patina of the diminishing supply of things he had touched.

I asked the administrative coordinator if she thought a cooking program might work upstairs.

"I don't really know," she said, smiling politely.

<...