Politics & Government

- Publisher : One World

- Published : 06 Jun 2023

- Pages : 368

- ISBN-10 : 0812989651

- ISBN-13 : 9780812989656

- Language : English

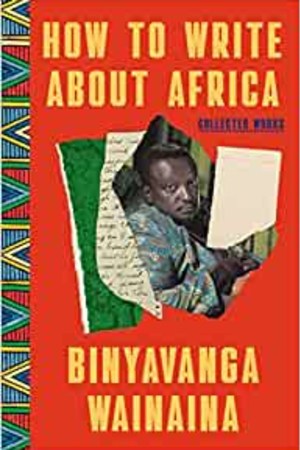

How to Write About Africa: Collected Works

From one of Africa's most influential and eloquent essayists, a posthumous collection that highlights his biting satire and subversive wisdom on topics from travel to cultural identity to sexuality

"A fierce literary talent . . . [Wainaina] shines a light on his continent without cliché."-The Guardian

"Africa is the only continent you can love-take advantage of this. . . . Africa is to be pitied, worshipped, or dominated. Whichever angle you take, be sure to leave the strong impression that without your intervention and your important book, Africa is doomed."

Binyavanga Wainaina was a pioneering voice in African literature, an award-winning memoirist and essayist, and a gatherer of literary communities. Before his tragic death in 2019 at the age of forty-seven, he won the Caine Prize for African Writing and was named one of Time's 100 Most Influential People. His wildly popular essay "How to Write About Africa," an incisive and unapologetic piece exposing the harmful and racist ways Western media depicts Africa with implicit bias and subjective clichés, changed the game for African writers and helped set the stage for a new generation of authors, from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to Yaa Gyasi. When Wainaina published a "lost chapter" of his 2011 memoir as an essay called "I Am a Homosexual, Mum," which imagines coming out to his mother, he became a voice for the queer African community as well, adding a new layer to how African sexuality is perceived.

How to Write About Africa collects these powerful pieces in a lively and imaginative set of essays about sexuality, art, history, and contemporary Africa. Wainaina's writing is playful, robust, generous, and full-bodied. He describes the modern world with sensual, emotional, and psychological detail, giving us a full-color view of a country and continent. These works present a portrait of a giant in African literature who left a tremendous legacy.

"A fierce literary talent . . . [Wainaina] shines a light on his continent without cliché."-The Guardian

"Africa is the only continent you can love-take advantage of this. . . . Africa is to be pitied, worshipped, or dominated. Whichever angle you take, be sure to leave the strong impression that without your intervention and your important book, Africa is doomed."

Binyavanga Wainaina was a pioneering voice in African literature, an award-winning memoirist and essayist, and a gatherer of literary communities. Before his tragic death in 2019 at the age of forty-seven, he won the Caine Prize for African Writing and was named one of Time's 100 Most Influential People. His wildly popular essay "How to Write About Africa," an incisive and unapologetic piece exposing the harmful and racist ways Western media depicts Africa with implicit bias and subjective clichés, changed the game for African writers and helped set the stage for a new generation of authors, from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to Yaa Gyasi. When Wainaina published a "lost chapter" of his 2011 memoir as an essay called "I Am a Homosexual, Mum," which imagines coming out to his mother, he became a voice for the queer African community as well, adding a new layer to how African sexuality is perceived.

How to Write About Africa collects these powerful pieces in a lively and imaginative set of essays about sexuality, art, history, and contemporary Africa. Wainaina's writing is playful, robust, generous, and full-bodied. He describes the modern world with sensual, emotional, and psychological detail, giving us a full-color view of a country and continent. These works present a portrait of a giant in African literature who left a tremendous legacy.

Editorial Reviews

"It's beginning to seem like Binyavanga Wainaina's satirical essay ‘How to Write About Africa' might be, after the Bible, the most read English-language text on the African continent. . . . This collection of his writing-the first to be published since he died-makes it difficult not to feel the scale of [his] loss. . . . A fierce literary talent . . . [Wainaina] shines a light on his continent without cliché."-The Guardian

Readers Top Reviews

ParabolaParabola

This book was a revelation. It blew my mind; I laughed out loud, I grimaced, I cried, and I learnt what it means to take the beauty of ordinary, everyday life on the African continent seriously. Binyavanga writes of his country, Kenya, his adopted home South Africa, as well as a host of other African countries (Senegal, Togo, Nigeria and more). His appreciation of everyday details is astonishing. If you're like me (suspicious of patronizing do-gooders, curious about what lies behind the faces of suffering and sorrow) you'll love it. For the earnest, however, or stridently leftist, this is probably not the book for you. But if you're willing to believe that people who live on the African continent might be more than merely recipients of western sympathy, you will not regret reading a single page of this book.

Short Excerpt Teaser

1

Binguni!

Two goldfish were arguing in their bowl: "If there is no God, who changes our water every week?"

Allotropy: (ə-ˈlä-trə-pē) n. The property of certain elements to exist in two or more distinct forms.

I

Dawn, December 27, 1999

Jango had often pictured his imagination as a helium-filled balloon, rather than one containing air. As he rose above the wreckage of the car, a whole-body feeling came over him. His life had ended, the string was cut, and his imagination was free to merge with reality. He felt immensely liberated-like he was flexing muscles that had not been used in a long time.

Oh, to stretch! His body felt loose-limbed and weightless, and his mind poised to soar. How could he have stayed in cramped earthliness for so long? How could he have forgotten this feeling? Had he not once danced with stars and had dalliances with gods?

Was he dreaming? Or was this part of some spectral past life? He felt no trauma of the type normally associated with violent death. Right now, he was rather piqued that he had missed out on the nonstop partying that was taking place all over the world. He hugged himself and found that his body seemed intact. He found it odd that he did not seem to feel the trepidation he would have expected if there was a possibility that he was destined for Pastor Vimba's "LAKE OF FIYYRRE!," which starred a leering Red Devil and promised "EEETERNALL DAMNATIONNN!" He giggled at the thought. "Tsk, tsk, Jango," he said to himself. "You're getting above yourself!"

Oddly enough, right now the thought of going to "Heaven" and spending eternity dressed in white robes, blissfully ensconced behind Pearly Gates while drinking nectar or listening to harps, was depressing. After spending most of his life in Johannesburg, and especially after the hedonism of the past few days, the "fires of hell" acquired a certain appeal.

There was another possible destination, though. His father's mania-to become an esteemed ancestor, as Zulu tradition dictated. Yet he could not visualize himself tolerating eternity as an "Outraged Ancestor," imposing droughts and plagues on disobedient descendants and anybody else who happened to be in the vicinity. Ancestor worship was a religion his father had tried to drum (quite often literally) into his head, and it was one he had discarded with relief. The concept of ancestors scrutinizing and guiding people's lives had always inspired images of power-mad old voyeurs playing African roulette (giggle, giggle . . . whom shall we play with next-Rwanda?).

What if one descended from a long line of assholes?

He thought to himself that if he had a choice, he would not mind being dispatched to some sort of Spectral Cyberspace, if such a fanciful place could exist. Hmm, yes. Maybe he was on his way to a place where nobody would dictate to him how to live his life.

Oops.

Afterlife.

Pah! Banish the thought. There were probably harp-playing Censors lovingly denying souls/spirits/whatever their daily fix of Ambrosia if they did not conform.

As he floated with a sort of predetermined aimlessness, he delighted in his new rubber-bandy self, vaguely wondering why he seemed to have carried his body with him. Surely his real body was still getting intimate with the mangled metal of his car?

He looked down at the surrealistic African vista below him. It was as if, as the Earth relinquished its pull on him, he relinquished all the trauma that he expected to have felt after the accident-relinquished all the weighty emotions and burdensome responsibilities that did not endear themselves to his new weightless self.

Or maybe he was still stoned from the party.

Around and below him, the Earth had decided to stake its claim. A sudden gust of wind whipped itself up into a frenzy of anger, and lightning seared the ground. Thunder roared as if backing up the sky's claim on him. Massive, engorged clouds lay low and gave birth to reluctant raindrops.

This drama had no physical effect on him. It seemed that he was in a dimension beyond Earth now. He could not remain unmoved by her mourning, though. As the wind wailed in fury, he mimicked it, roaring his farewell to her.

Meanwhile, fast asleep at her home in Diepkloof, Soweto, Mama Jango moaned as the cloud of unformed premonition that floated past her house darkened her pedestrian dreams. A shadow of loss chilled her briefly. Later she would wonder, and trusty Pastor Vimba would come up with a satisfactory supernatural explanation.

Meanwhile, exultation welled in Jango as he looked below him and saw the grand panorama of the storm-enlivened city. A powerful love for what had bee...

Binguni!

Two goldfish were arguing in their bowl: "If there is no God, who changes our water every week?"

Allotropy: (ə-ˈlä-trə-pē) n. The property of certain elements to exist in two or more distinct forms.

I

Dawn, December 27, 1999

Jango had often pictured his imagination as a helium-filled balloon, rather than one containing air. As he rose above the wreckage of the car, a whole-body feeling came over him. His life had ended, the string was cut, and his imagination was free to merge with reality. He felt immensely liberated-like he was flexing muscles that had not been used in a long time.

Oh, to stretch! His body felt loose-limbed and weightless, and his mind poised to soar. How could he have stayed in cramped earthliness for so long? How could he have forgotten this feeling? Had he not once danced with stars and had dalliances with gods?

Was he dreaming? Or was this part of some spectral past life? He felt no trauma of the type normally associated with violent death. Right now, he was rather piqued that he had missed out on the nonstop partying that was taking place all over the world. He hugged himself and found that his body seemed intact. He found it odd that he did not seem to feel the trepidation he would have expected if there was a possibility that he was destined for Pastor Vimba's "LAKE OF FIYYRRE!," which starred a leering Red Devil and promised "EEETERNALL DAMNATIONNN!" He giggled at the thought. "Tsk, tsk, Jango," he said to himself. "You're getting above yourself!"

Oddly enough, right now the thought of going to "Heaven" and spending eternity dressed in white robes, blissfully ensconced behind Pearly Gates while drinking nectar or listening to harps, was depressing. After spending most of his life in Johannesburg, and especially after the hedonism of the past few days, the "fires of hell" acquired a certain appeal.

There was another possible destination, though. His father's mania-to become an esteemed ancestor, as Zulu tradition dictated. Yet he could not visualize himself tolerating eternity as an "Outraged Ancestor," imposing droughts and plagues on disobedient descendants and anybody else who happened to be in the vicinity. Ancestor worship was a religion his father had tried to drum (quite often literally) into his head, and it was one he had discarded with relief. The concept of ancestors scrutinizing and guiding people's lives had always inspired images of power-mad old voyeurs playing African roulette (giggle, giggle . . . whom shall we play with next-Rwanda?).

What if one descended from a long line of assholes?

He thought to himself that if he had a choice, he would not mind being dispatched to some sort of Spectral Cyberspace, if such a fanciful place could exist. Hmm, yes. Maybe he was on his way to a place where nobody would dictate to him how to live his life.

Oops.

Afterlife.

Pah! Banish the thought. There were probably harp-playing Censors lovingly denying souls/spirits/whatever their daily fix of Ambrosia if they did not conform.

As he floated with a sort of predetermined aimlessness, he delighted in his new rubber-bandy self, vaguely wondering why he seemed to have carried his body with him. Surely his real body was still getting intimate with the mangled metal of his car?

He looked down at the surrealistic African vista below him. It was as if, as the Earth relinquished its pull on him, he relinquished all the trauma that he expected to have felt after the accident-relinquished all the weighty emotions and burdensome responsibilities that did not endear themselves to his new weightless self.

Or maybe he was still stoned from the party.

Around and below him, the Earth had decided to stake its claim. A sudden gust of wind whipped itself up into a frenzy of anger, and lightning seared the ground. Thunder roared as if backing up the sky's claim on him. Massive, engorged clouds lay low and gave birth to reluctant raindrops.

This drama had no physical effect on him. It seemed that he was in a dimension beyond Earth now. He could not remain unmoved by her mourning, though. As the wind wailed in fury, he mimicked it, roaring his farewell to her.

Meanwhile, fast asleep at her home in Diepkloof, Soweto, Mama Jango moaned as the cloud of unformed premonition that floated past her house darkened her pedestrian dreams. A shadow of loss chilled her briefly. Later she would wonder, and trusty Pastor Vimba would come up with a satisfactory supernatural explanation.

Meanwhile, exultation welled in Jango as he looked below him and saw the grand panorama of the storm-enlivened city. A powerful love for what had bee...