Politics & Government

- Publisher : Modern Library

- Published : 09 Aug 2022

- Pages : 496

- ISBN-10 : 0593447603

- ISBN-13 : 9780593447604

- Language : English

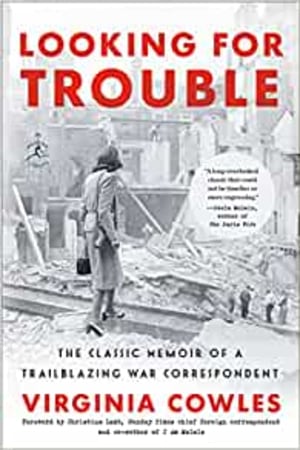

Looking for Trouble: The Classic Memoir of a Trailblazing War Correspondent

The rediscovered memoir of an American gossip columnist turned "amazingly brilliant reporter" (The New York Times Book Review) as she reports from the frontlines of the Spanish Civil War and World War II

"A long-overlooked classic that could not be timelier or more engrossing."-Paula McLain, author of The Paris Wife

Foreword by Christina Lamb, Sunday Times chief foreign correspondent and co-author of I Am Malala

Virginia Cowles was just twenty-seven years old when she decided to transform herself from a society columnist into a foreign press correspondent. Looking for Trouble is the story of this evolution, as Cowles reports from both sides of the Spanish Civil War, London on the first day of the Blitz, Nazi-run Munich, and Finland's bitter, bloody resistance to the Russian invasion. Along the way, Cowles also meets Adolf Hitler ("an inconspicuous little man"), Benito Mussolini, Winston Churchill, Martha Gellhorn, and Ernest Hemingway. Her reportage blends sharp political analysis with a gossip columnist's chatty approachability and a novelist's empathy.

Cowles understood in 1937-long before even the average politician-that Fascism in Europe was a threat to democracy everywhere. Her insights on extremism are as piercing and relevant today as they were eighty years ago.

"A long-overlooked classic that could not be timelier or more engrossing."-Paula McLain, author of The Paris Wife

Foreword by Christina Lamb, Sunday Times chief foreign correspondent and co-author of I Am Malala

Virginia Cowles was just twenty-seven years old when she decided to transform herself from a society columnist into a foreign press correspondent. Looking for Trouble is the story of this evolution, as Cowles reports from both sides of the Spanish Civil War, London on the first day of the Blitz, Nazi-run Munich, and Finland's bitter, bloody resistance to the Russian invasion. Along the way, Cowles also meets Adolf Hitler ("an inconspicuous little man"), Benito Mussolini, Winston Churchill, Martha Gellhorn, and Ernest Hemingway. Her reportage blends sharp political analysis with a gossip columnist's chatty approachability and a novelist's empathy.

Cowles understood in 1937-long before even the average politician-that Fascism in Europe was a threat to democracy everywhere. Her insights on extremism are as piercing and relevant today as they were eighty years ago.

Editorial Reviews

"Virginia Cowles went looking for trouble, and did she find it. . . . Her beauty, savvy and sheer impudence regularly got her to places no other woman reporter of the time could reach. . . . A tour-de-force."-Daily Mail

"[Virginia] Cowles was not only a doggedly ambitious reporter but one whose glamour facilitated unique access to her subjects. . . . Looking for Trouble is a rollicking thriller of a memoir."-The Wall Street Journal

"In all its diverse richness of drama and compassion and penetration and wit [Looking for Trouble] shows us the relentless progress of tragically integrated events, in a world where democratic civilization itself was fatally ‘looking for trouble' by trying with all its might to look the other way."-The New York Times Book Review

"One of the truly great war correspondents of all time."-Antony Beevor, New York Times bestselling author of Stalingrad and Berlin

"A society gossip columnist who arrived at her first front in heels and fur, Ginny Cowles would become, like her friend and sister in arms Martha Gellhorn, one of the most penetrating and effective war correspondents of all time. With its bold, unforgettable voice, and insight into ordinary people in peril-the ‘tragedy of smashed lives'-Looking for Trouble is a long-overlooked classic that could not be timelier or more engrossing."-Paula McLain, author of The Paris Wife and When the Stars Go Dark

"Reading this book. . . I was blown away. . . . Cowles's encounters with all the key players have led some to describe her as the Forrest Gump of journalism. . . . Indeed, her own story was as remarkable as the subjects she covered. . . . If today there are almost as many women as men reporting from war zones, it is thanks to women like Cowles, who showed what is possible. It's a mystery to me that she doesn't receive the same recognition as [Martha] Gellhorn. Looking for Trouble was a bes...

"[Virginia] Cowles was not only a doggedly ambitious reporter but one whose glamour facilitated unique access to her subjects. . . . Looking for Trouble is a rollicking thriller of a memoir."-The Wall Street Journal

"In all its diverse richness of drama and compassion and penetration and wit [Looking for Trouble] shows us the relentless progress of tragically integrated events, in a world where democratic civilization itself was fatally ‘looking for trouble' by trying with all its might to look the other way."-The New York Times Book Review

"One of the truly great war correspondents of all time."-Antony Beevor, New York Times bestselling author of Stalingrad and Berlin

"A society gossip columnist who arrived at her first front in heels and fur, Ginny Cowles would become, like her friend and sister in arms Martha Gellhorn, one of the most penetrating and effective war correspondents of all time. With its bold, unforgettable voice, and insight into ordinary people in peril-the ‘tragedy of smashed lives'-Looking for Trouble is a long-overlooked classic that could not be timelier or more engrossing."-Paula McLain, author of The Paris Wife and When the Stars Go Dark

"Reading this book. . . I was blown away. . . . Cowles's encounters with all the key players have led some to describe her as the Forrest Gump of journalism. . . . Indeed, her own story was as remarkable as the subjects she covered. . . . If today there are almost as many women as men reporting from war zones, it is thanks to women like Cowles, who showed what is possible. It's a mystery to me that she doesn't receive the same recognition as [Martha] Gellhorn. Looking for Trouble was a bes...

Readers Top Reviews

F. SchollMarinaA.

I picked this book up quite by accident, not knowing what to expect. It is really an amazing story of the outbreak of WWII as seen by the people across Europe. Very well written and full of insight. Highly recommended to anyone interested in this era.

ElizabethF. Schol

This book changed who I want to be as a person. How brave and totally cool Virginia was! Here are three reasons why I will read this book again and again: 1. In the face of crazy, real danger, Virginia charges into the world to get "the story." If I can bring just a little of that to my non-dangerous life, I'll be a better person for it. 2. Learning about this time in history from a real-person account taught me more than any class ever did. 3. Virginia was a truly great writer. The book reads like butter. I encourage everyone to read this book, but, especially anyone who wants to know what spunk really is.

pudgeElizabethF.

Most books about pre-WW2 Europe are written well after the results were known. This book was written as history was happening in real time by a writer while she was witnessing the events firsthand. The writing is fresh and immediate -- Virginia Cowles went directly to the center of the action. She witnessed the Spanish civil war from both sides, interviewed Mussolini twice, saw Hitler's famous speech at Nuremberg, bumped into Goebbels in a hotel lobby and knew Winston Churchill and his family. I am surprised this is such an obscure book today.

Randy Grindingerp

I’ve always enjoyed books by reporters about their adventures covering the news or historical events. This one came out in 1941 about events leading up to WW2, and by a woman, which added a twist. I’m convinced it set a standard for those to follow. I also detected a resemblance to Winds of War by Herman Wouk in 1971.

Richard BarefordR

Virginia Cowles (1910-1983) is by far the most fascinating character in her book. She knows everyone personally or is friends with someone who does, pulling strings with diplomats, politicians, generals, society figures and fellow journalists to get her scoops. But she doesn't overlook the "ordinary" people she encounters, vignettes that are always compassionate and occasionally comic. She is not averse to using her femininity to cut through red tape and escape sticky situations. There is no hint of romance despite innumerable opportunities. She lands private interviews with Mussolini and Chamberlain, sings Auld Lang Syne with Churchill, is a guest at a banquet for Hitler, covers the Czech crisis from Prague and Munich, is in Berlin when war is declared, gets bombed in Spain by the Germans and in Finland by the Russians, visits Paris the day before it falls, watches the Battle of Britain lying in an English meadow, and resides in London during the Blitz. Like her friend Martha Gellhorn, she is unsparing of British, French and American policies that facilitated Hitler's rise. The book itself is a reproduction of the 1941 Harper & Brothers edition, copied from a clean library holding, 447 pages with index. It's a slick hardcover, solidly bound, the pages unmarred except by a few library stamps. In one instance several words are obscured. Four pages are duplicated. Overall impression, professionally done.

Short Excerpt Teaser

Part I

Republican Spain

1

Trip to War

If you look back over the newspapers of March 1937 you will recall a number of things: that the Normandie beat the record for the Atlantic crossing; that King Leopold visited London; that Neville Chamberlain succeeded Stanley Baldwin as Prime Minister of England; that the lost diary of Dr. Samuel Johnson was found; that Queen Marie of Romania was gravely ill; and that Noël Coward was resting.

You will also read that General Franco launched an offensive. On March 10th the newspapers reported that he had broken through the Madrid defenses and on the following day the correspondent of the London Daily Telegraph wrote:

The Nationalists have advanced eighteen miles in two days. They are now fifteen miles from Guadalajara. The defenders of Madrid realize that the battle of Guadalajara will decide the fate of the capital.

A few days later the story began to trickle out and the world learned that not only was Madrid still standing, but that Franco's Italian Legionaries had broken and fled, and the Nationalist offensive had been turned into the first (and what proved to be the last) major victory for the Republic.

It was a week after the battle of Guadalajara that I made my first trip to Spain. I stood at the Toulouse aerodrome at five-thirty in the morning waiting for an airplane to take me to Valencia. It was pitch black and bitterly cold. The frost on the ground shimmered through the darkness like a ghostly shroud, and the small red bulbs outlining the airfield had an eerie glow. My heart began to sink at the prospect of the trip.

I had no qualifications as a war correspondent except curiosity. Although I had travelled in Europe and the Far East a good deal, and written a number of articles, mainly for the "March of Events' section of the Hearst newspapers, my adventures were of a peaceful nature. In fact, after a twelve-month trip from London to Tokyo in 1934, I had written an article for Harper's Bazaar which soon dated sadly. It was entitled: "The Safe, Safe World."

When the war broke out in Spain, I saw an opportunity for more vigorous reporting; I thought it would be interesting to cover both sides and write a series of articles contrasting the two. I persuaded Mr. T. V. Ranck of the Hearst newspapers that this was a good proposition and happily set off for Europe. I knew no one in Spain and hadn't the least idea how one went about such an assignment, so waited until reaching Paris before mapping out a plan of campaign. And then the battle of Guadalajara took place. I read about the heroic resistance of beleaguered Madrid, and decided that Madrid was obviously the place to go.

Friends in Paris were not encouraging. They warned me if I didn't dress shabbily I would be "bumped off" in the streets; some suggested men's clothes; others rags and tatters. I finally took three wool dresses and a fur jacket.

They also filled me with atrocity stories and gloomily predicted that if I was not shot down on the flight to Valencia I would surely be bombed on the road to Madrid. I had paid no attention to their forebodings, but now, as I stood on the aerodrome, a procession of terrible pictures filtered through my mind. I went into the waiting room to have a cup of coffee and took comfort from the fact that no one seemed impressed by the imminent departure of a plane for the perils of "war-torn" Spain. There were only a half-dozen people in the room; some reading yesterday's evening papers, some sleeping with their heads on the tables. It was so cold the French mechanics were pacing up and down, stopping every now and then to warm their hands over a small stove. At last the door opened and a man announced the plane was ready to leave. I paid my bill, and as I got up an old man in a black beret who had been sitting quietly by the fire walked over to me, clasped my hand, and in a voice trembling with emotion said: "Bonne chance, mademoiselle, bonne chance." I stepped into the airplane with a feeling of doom.

It took us only an hour to reach Barcelona. Most of it was spent in flying over the Pyrenees. The mountains were covered with snow and at first they looked grey and remote; then the dawn came up and they were swept with a fiery pink. When we circled down to a landing and I walked into the airport waiting room, I remember the surprise I felt at my first picture of Spain. The scene was so peaceful it was almost incongruous. A woman sat behind the counter knitting a sweater, two old gentlemen in black corduroy suits were at a table drinking brandy, and a small girl sprawled on the floor with a cat. They greeted the French pilots cordially, but when the latter commented on the war and asked for the latest n...

Republican Spain

1

Trip to War

If you look back over the newspapers of March 1937 you will recall a number of things: that the Normandie beat the record for the Atlantic crossing; that King Leopold visited London; that Neville Chamberlain succeeded Stanley Baldwin as Prime Minister of England; that the lost diary of Dr. Samuel Johnson was found; that Queen Marie of Romania was gravely ill; and that Noël Coward was resting.

You will also read that General Franco launched an offensive. On March 10th the newspapers reported that he had broken through the Madrid defenses and on the following day the correspondent of the London Daily Telegraph wrote:

The Nationalists have advanced eighteen miles in two days. They are now fifteen miles from Guadalajara. The defenders of Madrid realize that the battle of Guadalajara will decide the fate of the capital.

A few days later the story began to trickle out and the world learned that not only was Madrid still standing, but that Franco's Italian Legionaries had broken and fled, and the Nationalist offensive had been turned into the first (and what proved to be the last) major victory for the Republic.

It was a week after the battle of Guadalajara that I made my first trip to Spain. I stood at the Toulouse aerodrome at five-thirty in the morning waiting for an airplane to take me to Valencia. It was pitch black and bitterly cold. The frost on the ground shimmered through the darkness like a ghostly shroud, and the small red bulbs outlining the airfield had an eerie glow. My heart began to sink at the prospect of the trip.

I had no qualifications as a war correspondent except curiosity. Although I had travelled in Europe and the Far East a good deal, and written a number of articles, mainly for the "March of Events' section of the Hearst newspapers, my adventures were of a peaceful nature. In fact, after a twelve-month trip from London to Tokyo in 1934, I had written an article for Harper's Bazaar which soon dated sadly. It was entitled: "The Safe, Safe World."

When the war broke out in Spain, I saw an opportunity for more vigorous reporting; I thought it would be interesting to cover both sides and write a series of articles contrasting the two. I persuaded Mr. T. V. Ranck of the Hearst newspapers that this was a good proposition and happily set off for Europe. I knew no one in Spain and hadn't the least idea how one went about such an assignment, so waited until reaching Paris before mapping out a plan of campaign. And then the battle of Guadalajara took place. I read about the heroic resistance of beleaguered Madrid, and decided that Madrid was obviously the place to go.

Friends in Paris were not encouraging. They warned me if I didn't dress shabbily I would be "bumped off" in the streets; some suggested men's clothes; others rags and tatters. I finally took three wool dresses and a fur jacket.

They also filled me with atrocity stories and gloomily predicted that if I was not shot down on the flight to Valencia I would surely be bombed on the road to Madrid. I had paid no attention to their forebodings, but now, as I stood on the aerodrome, a procession of terrible pictures filtered through my mind. I went into the waiting room to have a cup of coffee and took comfort from the fact that no one seemed impressed by the imminent departure of a plane for the perils of "war-torn" Spain. There were only a half-dozen people in the room; some reading yesterday's evening papers, some sleeping with their heads on the tables. It was so cold the French mechanics were pacing up and down, stopping every now and then to warm their hands over a small stove. At last the door opened and a man announced the plane was ready to leave. I paid my bill, and as I got up an old man in a black beret who had been sitting quietly by the fire walked over to me, clasped my hand, and in a voice trembling with emotion said: "Bonne chance, mademoiselle, bonne chance." I stepped into the airplane with a feeling of doom.

It took us only an hour to reach Barcelona. Most of it was spent in flying over the Pyrenees. The mountains were covered with snow and at first they looked grey and remote; then the dawn came up and they were swept with a fiery pink. When we circled down to a landing and I walked into the airport waiting room, I remember the surprise I felt at my first picture of Spain. The scene was so peaceful it was almost incongruous. A woman sat behind the counter knitting a sweater, two old gentlemen in black corduroy suits were at a table drinking brandy, and a small girl sprawled on the floor with a cat. They greeted the French pilots cordially, but when the latter commented on the war and asked for the latest n...