Short Stories & Anthologies

- Publisher : Mariner Books; First Edition Thus

- Published : 01 Jun 1999

- Pages : 198

- ISBN-10 : 039592720X

- ISBN-13 : 9780395927205

- Language : English

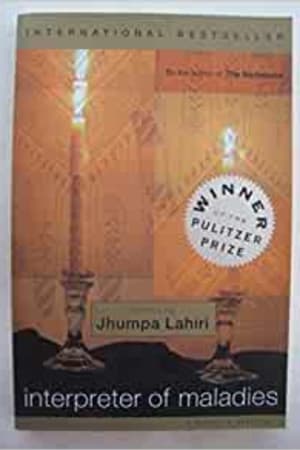

Interpreter of Maladies

With a new Introduction from the author for the twentieth anniversary

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, this stunning debut collection unerring charts the emotional journeys of characters seeking love beyond the barriers of nations and generations. In stories that travel from India to America and back again, Lahiri speaks with universal eloquence to everyone who has ever felt like a foreigner.

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, this stunning debut collection unerring charts the emotional journeys of characters seeking love beyond the barriers of nations and generations. In stories that travel from India to America and back again, Lahiri speaks with universal eloquence to everyone who has ever felt like a foreigner.

Editorial Reviews

"A writer of uncommon sensitivity and restraint."-Wall Street Journal

"Lahiri breathers unpredictable life into the page, and the reader finished each story reseduced, wishing he could spend a whole novel with its characters."-The New York Times Book Review

"Lahiri's touch is delicate yet assured, leaving no room for flubbed notes or forced epiphanies."-The Los Angeles Times

"A writer of uncommon elegance and poise."-New York times

"Dazzling writing, an easy-to-carry paperback format and a budget-respecting price tag of $12: Jhumpa Lahiri's Interpreter of Maladies possesses these three qualities, making it my book of choice this summer every time someone asks for a recommendation...Simply put, Lahiri displays a remarkable maturity and ability to imagine other lives...[E]ach story offers something special. Jhumpa Lahiri's Interpreter of Maladies will reward readers."-USA Today

"[S]torytelling of surpassing kindness and skill."-The San Francisco Chronicle

"Jhumpa Lahiri is the kind of writer who makes you want to grab the next person you see and say, ‘Read this!'"-Amy Tan

"Lahiri breathers unpredictable life into the page, and the reader finished each story reseduced, wishing he could spend a whole novel with its characters."-The New York Times Book Review

"Lahiri's touch is delicate yet assured, leaving no room for flubbed notes or forced epiphanies."-The Los Angeles Times

"A writer of uncommon elegance and poise."-New York times

"Dazzling writing, an easy-to-carry paperback format and a budget-respecting price tag of $12: Jhumpa Lahiri's Interpreter of Maladies possesses these three qualities, making it my book of choice this summer every time someone asks for a recommendation...Simply put, Lahiri displays a remarkable maturity and ability to imagine other lives...[E]ach story offers something special. Jhumpa Lahiri's Interpreter of Maladies will reward readers."-USA Today

"[S]torytelling of surpassing kindness and skill."-The San Francisco Chronicle

"Jhumpa Lahiri is the kind of writer who makes you want to grab the next person you see and say, ‘Read this!'"-Amy Tan

Readers Top Reviews

WeAreWhatWeReadRober

Both the writing and the plotting are elegant and deceptively simple, and Ms Lahiri's short stories are a (gentle) pleasure to read. The language is unfussy and so are the characters - ordinary people caught in snippets of their ordinary lives. Yet what the characters symbolize is universal and they illuminate the human condition; they stay with you long after you've read them. And Lahiri's observations are superb: fascinating, wonderfully detailed insights into exotic but everyday lives. The ruthlessly economical language, overall, does risk creating the impression of cold detachment. Jhumpa Lahiri lists the great Alice Munro among her literary heroes and the influence is easy to detect. I for one happen to love Munro therefore liked Lahiri very much indeed. And it's true, the book has the faults all short stories collections usually suffer from: read in isolation, each story is interesting, even startling. Each story is also masterfully complete and left me satisfied with the amount of detail about each character, and with the ending. But as a whole book, the stories become repetitive. I quickly found the characters to resemble each other throughout, and that I had read the same story too many times, in this book and elsewhere. The affair between a young woman and an older, married man has been done to death, surely, and so has the young or not so young couple falling out of love. Furthermore, here, unfortunately, the unrelenting stylistic simplicity (the very thing which, for me, defines great writing) ends up feeling a little like dullness, and the author's elegant objectivity could push the reader into feeling disengaged and therefore uninterested. 'Interpreter of Maladies' certainly cannot be described as unputdownable; in fact, it is best to put the book down after one, maximum two stories, and come back to it much later. That being said, there are a few stories to which I shall return with delight, for sure.

Edge of Chaos

For me, the common theme of this book is “Longing”. I like her lack of sentimentality - she neither judges nor makes excuses for her characters. She takes us on a journey from the self inflicted misery of her characters to later stories where her characters get it together. Her writing is fluid like an essay but without the cold smart ass intellectuality that haunts many “literary” novels. She has a gift to make the ordinary extraordinary. Now for a few splashes of vinegar. The opening stories are far too long and my attention wandered. Maybe her editor asked her to pad it out. Some of her description of clothes were too detailed and bordered on the tedious. Clothes descriptions should be enough to fit the character. I like the descriptions of food - they added to the ambience and were appropriate. Finally her use of rhetoric is very effective and writers should learn those valuable tools. So an excellent read and a masterclass in how to craft a short story.

Erol Esen

Mrs. Dal is a young Indian-American woman who lives in the United States with her husband and kinds. The family decides to visit India for vacation and take an excursion with an Indian driver named Mr. Kapasi, who is an interpreter of people from different villages with different dialects and even languages to the doctors in the closest city to these villages. While Mrs. Dal is a bit snotty, she is yet delicate in her beauty and frustration as most married women are, and gives the rarest of the world's commodities to Mr. Kapasi: attention. The plot's suspense in how Mr. Kapasi interprets Mrs. Dal's maladies. Great stories must have a great ending, this one does with a great release, and much satisfaction for the reader.

Cathryn Conroy

These nine very different short stories have one thing in common: They are all stories of love and loss, happiness and sadness as people adjust to the human condition. From adultery to abandonment, loneliness to falling deeply in love, each of the stories in this stellar, Pulitzer Prize-winning collection by Jhumpa Lahiri is absolutely brilliant. I thought "When Mr. Pirzada Came to Dine" was the most poignant and imaginative of the collection. It told of the crushing heartache of the 1971 civil war in Pakistan, but it's all seen through the eyes of a 10-year-old Indian girl who lives in Massachusetts and the man who dines with her family daily as he worries about his family caught in the crossfires of the war. My favorite was "This Blessed House" about Indian newlyweds who move into a house and keep finding Christian paraphernalia hidden in the home—from a porcelain effigy of Jesus to a 3D postcard of St. Francis to a statue of the Virgin Mary. The husband is annoyed, while the wife thinks it's hilarious. How they resolve it says much about their marriage. This is an extraordinary collection of literature that is a delight to read.

Timothy Haugh

As readers of my reviews might know, I think it’s too bad that short story collections are not as widely read as they used to be. In many ways, it’s understandable. At one time, reading a short story would have been a nice evening’s entertainment. Now, there is too much competition with novels, movies, TV, the internet, etc. The short story is fading as is the short story collection. There is also the fact that even the best short story collections are hits and misses. It is rare to find a collection that is more hits than misses. Fortunately, this is one. Most of the stories here are very well done. “When Mr. Pirzada Came to Dine”, the title story “Interpreter of Maladies”, “Sexy”, “Mrs. Sen’s”, “This Blessed House” and “The Third and Final Continent” are all top-notch tales. They all invoke the flavor of India. Some are set in India, some are set in America among Indian-Americans or recent immigrants from India. Ms. Lahiri has a deft touch when showing us the different points of view that culture can cause. In the title story, for example, a young American couple of Indian heritage is visiting India with their children. They are being shown around by an older guide called Mr. Kapasi. Over the course of their day together, Mr. Kapasi becomes enamored of the young wife when she glorifies his day job as a translator for doctors, an interpreter of maladies. He fantasizes a growing friendship between them only to realize that they see things very differently. They will not be able to bridge the distance. It is a wonderful examination of people. Of course, the Indian themes are so pervasive that it can be overwhelming for someone with little knowledge of the culture or someone who has little interest in the culture. It can be helpful to space the reading of the stories out a bit to let each unique experience soak in before moving on to the next. But these are stories definitely worth the time.

Short Excerpt Teaser

Chapter One

A Temporary Matter

The notice informed them that it was a temporary matter: for five

days their electricity would be cut off for one hour, beginning at

eight P.M. A line had gone down in the last snowstorm, and the

repairmen were going to take advantage of the milder evenings to set

it right. The work would affect only the houses on the quiet tree-

lined street, within walking distance of a row of brick-faced stores

and a trolley stop, where Shoba and Shukumar had lived for three

years.

"It's good of them to warn us," Shoba conceded after reading the

notice aloud, more for her own benefit than Shukumar's. She let the

strap of her leather satchel, plump with files, slip from her

shoulders, and left it in the hallway as she walked into the kitchen.

She wore a navy blue poplin raincoat over gray sweatpants and white

sneakers, looking, at thirty-three, like the type of woman she'd once

claimed she would never resemble.

She'd come from the gym. Her cranberry lipstick was visible only on

the outer reaches of her mouth, and her eyeliner had left charcoal

patches beneath her lower lashes. She used to look this way

sometimes, Shukumar thought, on mornings after a party or a night at

a bar, when she'd been too lazy to wash her face, too eager to

collapse into his arms. She dropped a sheaf of mail on the table

without a glance. Her eyes were still fixed on the notice in her

other hand. "But they should do this sort of thing during the day."

"When I'm here, you mean," Shukumar said. He put a glass lid on a pot

of lamb, adjusting it so only the slightest bit of steam could

escape. Since January he'd been working at home, trying to complete

the final chapters of his dissertation on agrarian revolts in

India. "When do the repairs start?"

"It says March nineteenth. Is today the nineteenth?" Shoba walked

over to the framed corkboard that hung on the wall by the fridge,

bare except for a calendar of William Morris wallpaper patterns. She

looked at it as if for the first time, studying the wallpaper pattern

carefully on the top half before allowing her eyes to fall to the

numbered grid on the bottom. A friend had sent the calendar in the

mail as a Christmas gift, even though Shoba and Shukumar hadn't

celebrated Christmas that year.

"Today then," Shoba announced. "You have a dentist appointment next

Friday, by the way."

He ran his tongue over the tops of his teeth; he'd forgotten to brush

them that morning. It wasn't the first time. He hadn't left the house

at all that day, or the day before. The more Shoba stayed out, the

more she began putting in extra hours at work and taking on

additional projects, the more he wanted to stay in, not even leaving

to get the mail, or to buy fruit or wine at the stores by the trolley

stop.

Six months ago, in September, Shukumar was at an academic conference

in Baltimore when Shoba went into labor, three weeks before her due

date. He hadn't wanted to go to the conference, but she had insisted;

it was important to make contacts, and he would be entering the job

market next year. She told him that she had his number at the hotel,

and a copy of his schedule and flight numbers, and she had arranged

with her friend Gillian for a ride to the hospital in the event of an

emergency. When the cab pulled away that morning for the airport,

Shoba stood waving good-bye in her robe, with one arm resting on the

mound of her belly as if it were a perfectly natural part of her

body.

Each time he thought of that moment, the last moment he saw Shoba

pregnant, it was the cab he remembered most, a station wagon, painted

red with blue lettering. It was cavernous compared to their own car.

Although Shukumar was six feet tall, with hands too big ever to rest

comfortably in the pockets of his jeans, he felt dwarfed in the back

seat. As the cab sped down Beacon Street, he imagined a day when he

and Shoba might need to buy a station wagon of their own, to cart

their children back and forth from music lessons and dentist

appointments. He imagined himself gripping the wheel, as Shoba turned

around to hand the children juice boxes. Once, these images of

parenthood had troubled Shukumar, adding to his anxiety that he was

still a student at thirty-five. But that early autumn morning, the

trees still heavy with bronze leaves, he welcomed the image for the

first time.

A member of the staff had found him somehow among the identical

convention rooms and handed him a stiff square of stationery. It was

only a telephone number, b...

A Temporary Matter

The notice informed them that it was a temporary matter: for five

days their electricity would be cut off for one hour, beginning at

eight P.M. A line had gone down in the last snowstorm, and the

repairmen were going to take advantage of the milder evenings to set

it right. The work would affect only the houses on the quiet tree-

lined street, within walking distance of a row of brick-faced stores

and a trolley stop, where Shoba and Shukumar had lived for three

years.

"It's good of them to warn us," Shoba conceded after reading the

notice aloud, more for her own benefit than Shukumar's. She let the

strap of her leather satchel, plump with files, slip from her

shoulders, and left it in the hallway as she walked into the kitchen.

She wore a navy blue poplin raincoat over gray sweatpants and white

sneakers, looking, at thirty-three, like the type of woman she'd once

claimed she would never resemble.

She'd come from the gym. Her cranberry lipstick was visible only on

the outer reaches of her mouth, and her eyeliner had left charcoal

patches beneath her lower lashes. She used to look this way

sometimes, Shukumar thought, on mornings after a party or a night at

a bar, when she'd been too lazy to wash her face, too eager to

collapse into his arms. She dropped a sheaf of mail on the table

without a glance. Her eyes were still fixed on the notice in her

other hand. "But they should do this sort of thing during the day."

"When I'm here, you mean," Shukumar said. He put a glass lid on a pot

of lamb, adjusting it so only the slightest bit of steam could

escape. Since January he'd been working at home, trying to complete

the final chapters of his dissertation on agrarian revolts in

India. "When do the repairs start?"

"It says March nineteenth. Is today the nineteenth?" Shoba walked

over to the framed corkboard that hung on the wall by the fridge,

bare except for a calendar of William Morris wallpaper patterns. She

looked at it as if for the first time, studying the wallpaper pattern

carefully on the top half before allowing her eyes to fall to the

numbered grid on the bottom. A friend had sent the calendar in the

mail as a Christmas gift, even though Shoba and Shukumar hadn't

celebrated Christmas that year.

"Today then," Shoba announced. "You have a dentist appointment next

Friday, by the way."

He ran his tongue over the tops of his teeth; he'd forgotten to brush

them that morning. It wasn't the first time. He hadn't left the house

at all that day, or the day before. The more Shoba stayed out, the

more she began putting in extra hours at work and taking on

additional projects, the more he wanted to stay in, not even leaving

to get the mail, or to buy fruit or wine at the stores by the trolley

stop.

Six months ago, in September, Shukumar was at an academic conference

in Baltimore when Shoba went into labor, three weeks before her due

date. He hadn't wanted to go to the conference, but she had insisted;

it was important to make contacts, and he would be entering the job

market next year. She told him that she had his number at the hotel,

and a copy of his schedule and flight numbers, and she had arranged

with her friend Gillian for a ride to the hospital in the event of an

emergency. When the cab pulled away that morning for the airport,

Shoba stood waving good-bye in her robe, with one arm resting on the

mound of her belly as if it were a perfectly natural part of her

body.

Each time he thought of that moment, the last moment he saw Shoba

pregnant, it was the cab he remembered most, a station wagon, painted

red with blue lettering. It was cavernous compared to their own car.

Although Shukumar was six feet tall, with hands too big ever to rest

comfortably in the pockets of his jeans, he felt dwarfed in the back

seat. As the cab sped down Beacon Street, he imagined a day when he

and Shoba might need to buy a station wagon of their own, to cart

their children back and forth from music lessons and dentist

appointments. He imagined himself gripping the wheel, as Shoba turned

around to hand the children juice boxes. Once, these images of

parenthood had troubled Shukumar, adding to his anxiety that he was

still a student at thirty-five. But that early autumn morning, the

trees still heavy with bronze leaves, he welcomed the image for the

first time.

A member of the staff had found him somehow among the identical

convention rooms and handed him a stiff square of stationery. It was

only a telephone number, b...