Community & Culture

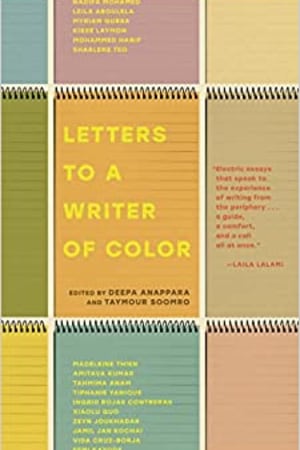

- Publisher : Random House Trade Paperbacks

- Published : 07 Mar 2023

- Pages : 272

- ISBN-10 : 059344941X

- ISBN-13 : 9780593449417

- Language : English

Letters to a Writer of Color

A vital collection of essays on the power of literature and the craft of writing from an international array of writers of color, sharing the experiences, cultural traditions, and convictions that have shaped them and their work

"Electric essays that speak to the experience of writing from the periphery . . . a guide, a comfort, and a call all at once."-Laila Lalami, author of Conditional Citizens

Filled with empathy and wisdom, instruction and inspiration, this book encourages us to reevaluate the codes and conventions that have shaped our assumptions about how fiction should be written, and also challenges us to apply its lessons to both what we read and how we read. Featuring:

• Taymour Soomro on resisting rigid stories about who you are

• Madeleine Thien on how writing builds the room in which it can exist

• Amitava Kumar on why authenticity isn't a license we carry in our wallets

• Tahmima Anam on giving herself permission to be funny

• Ingrid Rojas Contreras on the bodily challenge of writing about trauma

• Zeyn Joukhadar on queering English and the power of refusing to translate ourselves

• Myriam Gurba on the empowering circle of Latina writers she works within

• Kiese Laymon on hearing that no one wants to read the story that you want to write

• Mohammed Hanif on the censorship he experienced at the hands of political authorities

• Deepa Anappara on writing even through conditions that impede the creation of art

• Plus essays from Tiphanie Yanique, Xiaolu Guo, Jamil Jan Kochai, Vida Cruz-Borja, Femi Kayode, Nadifa Mohamed in conversation with Leila Aboulela, and Sharlene Teo

The start of a more inclusive conversation about storytelling, Letters to a Writer of Color will be a touchstone for aspiring and working writers and for curious readers everywhere.

"Electric essays that speak to the experience of writing from the periphery . . . a guide, a comfort, and a call all at once."-Laila Lalami, author of Conditional Citizens

Filled with empathy and wisdom, instruction and inspiration, this book encourages us to reevaluate the codes and conventions that have shaped our assumptions about how fiction should be written, and also challenges us to apply its lessons to both what we read and how we read. Featuring:

• Taymour Soomro on resisting rigid stories about who you are

• Madeleine Thien on how writing builds the room in which it can exist

• Amitava Kumar on why authenticity isn't a license we carry in our wallets

• Tahmima Anam on giving herself permission to be funny

• Ingrid Rojas Contreras on the bodily challenge of writing about trauma

• Zeyn Joukhadar on queering English and the power of refusing to translate ourselves

• Myriam Gurba on the empowering circle of Latina writers she works within

• Kiese Laymon on hearing that no one wants to read the story that you want to write

• Mohammed Hanif on the censorship he experienced at the hands of political authorities

• Deepa Anappara on writing even through conditions that impede the creation of art

• Plus essays from Tiphanie Yanique, Xiaolu Guo, Jamil Jan Kochai, Vida Cruz-Borja, Femi Kayode, Nadifa Mohamed in conversation with Leila Aboulela, and Sharlene Teo

The start of a more inclusive conversation about storytelling, Letters to a Writer of Color will be a touchstone for aspiring and working writers and for curious readers everywhere.

Editorial Reviews

"If you've ever felt that your creative choices were being dismissed or ignored in a fiction workshop, if you've been pressured to make your writing more ‘accessible,' if you've strained under the demand to write about certain things only and to silence others-this book is for you. It is a guide, a comfort, and a call all at once."-Laila Lalami, author of Conditional Citizens

"A brave and triumphant act of resistance and decolonization, a necessary resource for writers and educators alike, and a must-have book for readers who care about diversity and inclusion in literature. Reading this book, I felt seen and empowered."-Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai, bestselling author of The Mountains Sing and Dust Child

"Funny, moving, thought-provoking, default-challenging, engaging, and full of so much heart and so many voices, this book feels to me like nothing less than a revolution."-Melissa Fu, author of Peach Blossom Spring

"Witty, candid, bold, gutsy, eye-opening and sometimes eye-popping, revelatory and wise! If you want to know what writers talk about among themselves, you've found it."-Aminatta Forna, author of The Memory of Love

"A feast of delights: impassioned, funny, instructive, and energizing. Here, matters of craft are interwoven with those of personhood and politics, offering a global range of perspectives rarely found in books on writing. I cherish this book deeply, like a friend I've been waiting all my life to meet."-Tania James, author of Aerogrammes and The Tusk That Did the Damage

"A revelatory reading experience. A book that guides, teaches, and gives off its own shimmering light, that demands to be read and re-read. Letters to a Writer of Color should take its place at the forefront of the multitude of works on the art of writing and reading."-Katherine J. Chen, author of Joan

"The problem of the color line, as Web du Bois called it, has existed in literature and literary criticism as much as social and geopolitical realms, and systematic neglect by publishers, critics and rea...

"A brave and triumphant act of resistance and decolonization, a necessary resource for writers and educators alike, and a must-have book for readers who care about diversity and inclusion in literature. Reading this book, I felt seen and empowered."-Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai, bestselling author of The Mountains Sing and Dust Child

"Funny, moving, thought-provoking, default-challenging, engaging, and full of so much heart and so many voices, this book feels to me like nothing less than a revolution."-Melissa Fu, author of Peach Blossom Spring

"Witty, candid, bold, gutsy, eye-opening and sometimes eye-popping, revelatory and wise! If you want to know what writers talk about among themselves, you've found it."-Aminatta Forna, author of The Memory of Love

"A feast of delights: impassioned, funny, instructive, and energizing. Here, matters of craft are interwoven with those of personhood and politics, offering a global range of perspectives rarely found in books on writing. I cherish this book deeply, like a friend I've been waiting all my life to meet."-Tania James, author of Aerogrammes and The Tusk That Did the Damage

"A revelatory reading experience. A book that guides, teaches, and gives off its own shimmering light, that demands to be read and re-read. Letters to a Writer of Color should take its place at the forefront of the multitude of works on the art of writing and reading."-Katherine J. Chen, author of Joan

"The problem of the color line, as Web du Bois called it, has existed in literature and literary criticism as much as social and geopolitical realms, and systematic neglect by publishers, critics and rea...

Short Excerpt Teaser

On Origin Stories

Taymour Soomro

I collect stories about con artists. Often the stories stress what is purely, willfully manipulative in the con and its pursuit of simple financial gain, but what interests me more is the desire for a disguise, its art and effects.

Tom MacMaster, a cis-het white American, blogged as a Syrian lesbian. Sophie Hingst posed as the relative of Auschwitz survivors and sent "testimonies" to Israel's Yad Vashem memorial of people who had never existed. Belle Gibson, a wellness guru, claimed to have survived various cancers. Hargobind Tahilramani masqueraded as film studio executive Amy Pascal. And there's Rachel Dolezal, Anna Delvey, and Dan Mallory too. There is a public fascination with uncovering these cons, with unmasking a "true" identity underneath, with pathologizing these acts as sickness or crime.

But I feel a kind of affinity, perhaps even an uneasy kinship, with these actors. My identity seems to me unavoidably a performance and a disguise, not only because it seeks to constrain me in one persona when I am constantly in flux but also because there has always been a conflict between who I think I am at any given moment and who others think I am, so that my reflection flickers endlessly in a mirror. One of the features that distinguishes good fiction for me is that it captures this shiftiness of self, so that Anna Karenina or Rahel Ipe or Sethe cannot be constrained within a fixed identity, cannot easily be reduced to a set of character traits. I wonder then at the relationship between the stories I tell about myself and the stories I write. Where is the con and where is the truth?

These questions recur in Nabokov's formulation on fiction: "Literature was born on the day when a boy came crying wolf, wolf and there was no wolf behind him. . . . Between the wolf in the tall grass and the wolf in the tall story there is a shimmering go-between. That go-between, that prism, is the art of literature." For him, fiction is a commitment to untruth rather than truth. It is the ultimate, unimpeachable con.

When I left my job at a corporate law firm to write a novel, my greatest preoccupation was not that I would fail but that my fiction would unmask me. I was living a sort of double life at the time: queer in London but not in Karachi, desi in Karachi but as English as possible in London. This kind of life-of multiple selves, of one person in my head and another outside, of one person in one place and another elsewhere-was familiar to me. It was how I'd always been, but my ability to police these selves, to keep them separate, to keep separate the communities that knew me as one person and those that knew me as another, had become more difficult, once I left home at eighteen for university and began to live these lives rather than just to imagine them.

So when I sat down to write, I determined to write as far away from these selves as I could, "as though tossing a grenade," as the protagonist of my novel Other Names for Love says. To support myself, I tutored the children of wealthy Londoners. One of these was a young woman who had enrolled in a graduate program. First, I guided her through the writing process for a thesis on beauty myths and, when she did well on that, through the writing process for a subsequent thesis on the ethics of face transplantation.

My student preferred that we should read and make notes together and, as this was on the clock, it suited me. I spent hours in her Knightsbridge basement apartment reading aloud to her from articles and textbooks, dictating notes, interrupted occasionally by her mother, who would turn up with wads of fifty-pound notes to pay me, and her handsome Cypriot boyfriend, who, when he wasn't napping, drifted in and out of the living room in a short toweling robe which promised at any moment, if I paid sufficient attention, to reveal a glimpse of the inside of his thigh.

I was in search of a protagonist and a plot for my novel. My student, with her ennui, anxiety, and careless wealth, seemed like a character I could imagine piloting the kind of novels I'd read, and the subject matter of her thesis seemed topical and arbitrary enough that none of it could say anything about me at all: the perfect Keyser Söze. Over the two years that I taught her, I wrote, polishing and repolishing the first part of the manuscript. I bought that year's edition of a guidebook called The Writers' & Artists' Yearbook, which included an alphabetical list of British agents with brief descriptions, and sent three chapters and a cover letter to a selection of nine agents, who, within a couple of months, rejecte...

Taymour Soomro

I collect stories about con artists. Often the stories stress what is purely, willfully manipulative in the con and its pursuit of simple financial gain, but what interests me more is the desire for a disguise, its art and effects.

Tom MacMaster, a cis-het white American, blogged as a Syrian lesbian. Sophie Hingst posed as the relative of Auschwitz survivors and sent "testimonies" to Israel's Yad Vashem memorial of people who had never existed. Belle Gibson, a wellness guru, claimed to have survived various cancers. Hargobind Tahilramani masqueraded as film studio executive Amy Pascal. And there's Rachel Dolezal, Anna Delvey, and Dan Mallory too. There is a public fascination with uncovering these cons, with unmasking a "true" identity underneath, with pathologizing these acts as sickness or crime.

But I feel a kind of affinity, perhaps even an uneasy kinship, with these actors. My identity seems to me unavoidably a performance and a disguise, not only because it seeks to constrain me in one persona when I am constantly in flux but also because there has always been a conflict between who I think I am at any given moment and who others think I am, so that my reflection flickers endlessly in a mirror. One of the features that distinguishes good fiction for me is that it captures this shiftiness of self, so that Anna Karenina or Rahel Ipe or Sethe cannot be constrained within a fixed identity, cannot easily be reduced to a set of character traits. I wonder then at the relationship between the stories I tell about myself and the stories I write. Where is the con and where is the truth?

These questions recur in Nabokov's formulation on fiction: "Literature was born on the day when a boy came crying wolf, wolf and there was no wolf behind him. . . . Between the wolf in the tall grass and the wolf in the tall story there is a shimmering go-between. That go-between, that prism, is the art of literature." For him, fiction is a commitment to untruth rather than truth. It is the ultimate, unimpeachable con.

When I left my job at a corporate law firm to write a novel, my greatest preoccupation was not that I would fail but that my fiction would unmask me. I was living a sort of double life at the time: queer in London but not in Karachi, desi in Karachi but as English as possible in London. This kind of life-of multiple selves, of one person in my head and another outside, of one person in one place and another elsewhere-was familiar to me. It was how I'd always been, but my ability to police these selves, to keep them separate, to keep separate the communities that knew me as one person and those that knew me as another, had become more difficult, once I left home at eighteen for university and began to live these lives rather than just to imagine them.

So when I sat down to write, I determined to write as far away from these selves as I could, "as though tossing a grenade," as the protagonist of my novel Other Names for Love says. To support myself, I tutored the children of wealthy Londoners. One of these was a young woman who had enrolled in a graduate program. First, I guided her through the writing process for a thesis on beauty myths and, when she did well on that, through the writing process for a subsequent thesis on the ethics of face transplantation.

My student preferred that we should read and make notes together and, as this was on the clock, it suited me. I spent hours in her Knightsbridge basement apartment reading aloud to her from articles and textbooks, dictating notes, interrupted occasionally by her mother, who would turn up with wads of fifty-pound notes to pay me, and her handsome Cypriot boyfriend, who, when he wasn't napping, drifted in and out of the living room in a short toweling robe which promised at any moment, if I paid sufficient attention, to reveal a glimpse of the inside of his thigh.

I was in search of a protagonist and a plot for my novel. My student, with her ennui, anxiety, and careless wealth, seemed like a character I could imagine piloting the kind of novels I'd read, and the subject matter of her thesis seemed topical and arbitrary enough that none of it could say anything about me at all: the perfect Keyser Söze. Over the two years that I taught her, I wrote, polishing and repolishing the first part of the manuscript. I bought that year's edition of a guidebook called The Writers' & Artists' Yearbook, which included an alphabetical list of British agents with brief descriptions, and sent three chapters and a cover letter to a selection of nine agents, who, within a couple of months, rejecte...