True Crime

- Publisher : Knopf

- Published : 27 Jun 2023

- Pages : 240

- ISBN-10 : 0525657320

- ISBN-13 : 9780525657323

- Language : English

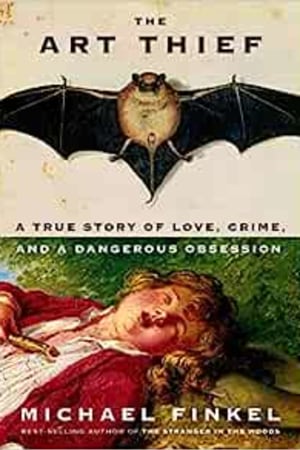

The Art Thief: A True Story of Love, Crime, and a Dangerous Obsession

One of the most remarkable true-crime narratives of the twenty-first century: the story of the world's most prolific art thief, Stéphane Breitwieser. • "The Art Thief, like its title character, has confidence, élan, and a great sense of timing."-The New Yorker

"Enthralling." -The Wall Street Journal

In this spellbinding portrait of obsession and flawed genius, the best-selling author of The Stranger in the Woods brings us into Breitwieser's strange world-unlike most thieves, he never stole for money, keeping all his treasures in a single room where he could admire them.

For centuries, works of art have been stolen in countless ways from all over the world, but no one has been quite as successful at it as the master thief Stéphane Breitwieser. Carrying out more than two hundred heists over nearly eight years-in museums and cathedrals all over Europe-Breitwieser, along with his girlfriend who worked as his lookout, stole more than three hundred objects, until it all fell apart in spectacular fashion.

In The Art Thief, Michael Finkel brings us into Breitwieser's strange and fascinating world. Unlike most thieves, Breitwieser never stole for money. Instead, he displayed all his treasures in a pair of secret rooms where he could admire them to his heart's content. Possessed of a remarkable athleticism and an innate ability to circumvent practically any security system, Breitwieser managed to pull off a breathtaking number of audacious thefts. Yet these strange talents bred a growing disregard for risk and an addict's need to score, leading Breitwieser to ignore his girlfriend's pleas to stop-until one final act of hubris brought everything crashing down.

This is a riveting story of art, crime, love, and an insatiable hunger to possess beauty at any cost.

"Enthralling." -The Wall Street Journal

In this spellbinding portrait of obsession and flawed genius, the best-selling author of The Stranger in the Woods brings us into Breitwieser's strange world-unlike most thieves, he never stole for money, keeping all his treasures in a single room where he could admire them.

For centuries, works of art have been stolen in countless ways from all over the world, but no one has been quite as successful at it as the master thief Stéphane Breitwieser. Carrying out more than two hundred heists over nearly eight years-in museums and cathedrals all over Europe-Breitwieser, along with his girlfriend who worked as his lookout, stole more than three hundred objects, until it all fell apart in spectacular fashion.

In The Art Thief, Michael Finkel brings us into Breitwieser's strange and fascinating world. Unlike most thieves, Breitwieser never stole for money. Instead, he displayed all his treasures in a pair of secret rooms where he could admire them to his heart's content. Possessed of a remarkable athleticism and an innate ability to circumvent practically any security system, Breitwieser managed to pull off a breathtaking number of audacious thefts. Yet these strange talents bred a growing disregard for risk and an addict's need to score, leading Breitwieser to ignore his girlfriend's pleas to stop-until one final act of hubris brought everything crashing down.

This is a riveting story of art, crime, love, and an insatiable hunger to possess beauty at any cost.

Editorial Reviews

"The Art Thief, like its title character, has confidence, élan, and a great sense of timing. It is propelled by suspense and surprises....This ultra-lucrative, odds-defying crime streak is wonderfully narrated by Finkel, in a tale whose trajectory is less rise and fall than crazy and crazier....Part of what makes Finkel's book so much fun is that, without exception, [Breitwieser's] strategies are insane."

-Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker

"A mesmerizing true-crime psychological thriller....The Art Thief develops the tension of a French policier, where the crook (for whom you alternately feel sympathy and disgust) has Maigret or Poirot hot on his trail. The final outcome is a shock. Mr. Finkel tells an enthralling story. From start to finish, this book is hard to put down."

-Moira Hodgson, The Wall Street Journal

"Meticulously detailed, [a] page-turning account....As much a crime caper as a psychological thriller, Finkel's narrative interweaves gripping descriptions of Breitweiser's in-plain-sight thefts armed with nothing more than stealth and a Swiss Army knife, a concise history of global art theft, and psychologists' musings on Breitwieser's unconscious motivations....Finkel deftly keeps us swaying between great sympathy for his central character and profound suspicion."

-Jenny McPhee, Air Mail

"It is romantic to liken art thieves to Pierce Brosnan's glamorous character in The Thomas Crown Affair. The reality is far less charming. Case in point: Stéphane Breitwieser, one of the most successful art thieves of all time. From roughly 1994 to 2001, Breitwieser executed more than 200 heists. The book's first lesson? Europe has a lot of understaffed historic buildings. The second? Even a kleptomaniac with delusions of grandeur can be made mildly sympathetic in the hands of a skilled writer."

-Bloomberg

"This is an absorbing and astonishing portrait of a fascinating and complicated character-a riveting story of obsession and misplaced brilliance."

-Kirk Wallace Johnson, best-selling author of The Feather Thief and ...

-Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker

"A mesmerizing true-crime psychological thriller....The Art Thief develops the tension of a French policier, where the crook (for whom you alternately feel sympathy and disgust) has Maigret or Poirot hot on his trail. The final outcome is a shock. Mr. Finkel tells an enthralling story. From start to finish, this book is hard to put down."

-Moira Hodgson, The Wall Street Journal

"Meticulously detailed, [a] page-turning account....As much a crime caper as a psychological thriller, Finkel's narrative interweaves gripping descriptions of Breitweiser's in-plain-sight thefts armed with nothing more than stealth and a Swiss Army knife, a concise history of global art theft, and psychologists' musings on Breitwieser's unconscious motivations....Finkel deftly keeps us swaying between great sympathy for his central character and profound suspicion."

-Jenny McPhee, Air Mail

"It is romantic to liken art thieves to Pierce Brosnan's glamorous character in The Thomas Crown Affair. The reality is far less charming. Case in point: Stéphane Breitwieser, one of the most successful art thieves of all time. From roughly 1994 to 2001, Breitwieser executed more than 200 heists. The book's first lesson? Europe has a lot of understaffed historic buildings. The second? Even a kleptomaniac with delusions of grandeur can be made mildly sympathetic in the hands of a skilled writer."

-Bloomberg

"This is an absorbing and astonishing portrait of a fascinating and complicated character-a riveting story of obsession and misplaced brilliance."

-Kirk Wallace Johnson, best-selling author of The Feather Thief and ...

Readers Top Reviews

John MJohn Mmobea

For the tiny minority that might care more about print size than the actual text written by the author, Amazon has made it clear that the paperback version utilizes large print. Bravo to them!

David ManueleJohn

After Longo and the Maine Hermit, leave it to Michael Finkel to expertly develop another fantastic but true story about three tragically conflicted individuals, such that your final assessment is not one of indignation but the saddest pathos. Isaac Babel was once asked what was the most important consideration about writing, and he replied that only the necessary was necessary. From Finkel's experience as an investigative reporter he achieves that rare ability to streamline the narrative such that he answers all of the questions a reader might have but goes no further with extraneous details. The compactness but completeness of the narrative makes us feel afterwards that we have read a longer book. There is perhaps no other nonfiction writer who can do this to such an impressive degree. Conrad in the introduction to the N of the Narcissus said that his intention was to make you "see"; Finkel's hard, flat realism enabled me to visualize almost every scene. Watch how Netflix will probably option this and create a series.

Nancy AdairDavid

When I love a work of art I buy a postcard or a print or snap a photo. That’s how I ‘own’ it. But Stéphane Breitwieser had an irresistible urge to steal the art that captured his heart. And he stole hundreds of works of art, filling his attic rooms in his mother’s house with more art that it could hold. Art by by Dutch masters including Cranach, Durer, and Brueghel, silverwork including chalices and a ship, a bugle gifted to Wagner, and even a tapestry were stashed in his crowded rooms. Breitwieser mostly targeted small museums, and with the aid of his look-out girlfriend, quickly dismantled display cases or removed art from its frame, stashed them under his coat or in a duffle bag, and walked out of the museum, calmly greeting the guards a good bye. The more successful he was, the greater risks he took. His girlfriend pleaded for it to end. His mother pretended she didn’t know. Breitwieser was caught one day before he even entered a museum he had stolen from before. I was fascinated by this story. Finkel’s research and interviews offer great detail and insight into Breitweiser’s motivation and personality and motivation. It’s a must-read for those who love true crime stories as well as art lovers. I received a free ebook from the publisher through NetGalley. My review is fair and unbiased.

Ken PNancy AdairD

Instantly read the book. It was good but overpriced and not available on Kindle. Wish it had come at the time it was promised.

Christian Schlect

Perfect entertainment for the traveler on a cross-country plane ride or an over-night train journey. An interesting but not too demanding study of a man in Europe who enjoyed certain museum art so much he took it home. How he did it and with whom, and most importantly "why" are important strands to this well-told tale. Both crime story and art history aficionados will enjoy Mr. Finkel's book.

Short Excerpt Teaser

1

Approaching the museum, ready to hunt, Stéphane Breitwieser clasps hands with his girlfriend, Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus, and together they stroll to the front desk and say hello, a cute couple. Then they purchase two tickets with cash and walk in.

It's lunchtime, stealing time, on a busy Sunday in Antwerp, Belgium, in February 1997. The couple blends with the tourists at the Rubens House, pointing and nodding at sculptures and oils. Anne-Catherine is tastefully dressed in Chanel and Dior bought in secondhand shops, a big Yves Saint Laurent bag on her shoulder. Breitwieser wears a button-down shirt tucked into stylish pants, topped by an overcoat that's sized a little too roomy, a Swiss Army knife stashed in a pocket.

The Rubens House is an elegant museum in the former residence of Peter Paul Rubens, the great Flemish painter of the seventeenth century. The couple drifts through the parlor and kitchen and dining room as Breitwieser memorizes the side doors and keeps track of the guards. Several escape routes take shape in his mind. The item they're hunting is sheltered at the rear of the museum, in a ground-floor gallery with a brass chandelier and soaring windows, some now shuttered to protect the works from the midday sun. Here, mounted atop an ornate wooden dresser, is a plexiglass display box fastened to a sturdy base. Sealed inside the box is an ivory sculpture of Adam and Eve.

Breitwieser had encountered the piece on a solo scouting trip a few weeks earlier and had fallen under its spell-the four-hundred-year-old carving still radiates the inner glow, unique to ivory, that feels to him transcendent. After that trip, he could not stop thinking of the sculpture, dreaming of it, so he has returned to the Rubens House with Anne-Catherine.

All forms of security have a weakness. The flaw with the plexiglass box, he had seen on his scouting visit, is that the upper part can be separated from the base by removing two screws. Tricky screws, sure, difficult to reach at the rear of the box, but just two. The flaw with the security guards is they're human. They get hungry. Most of the day, Breitwieser had observed, there is a guard in each gallery, watching from a chair. Except at lunchtime, when the chairs wait empty as the security staff rotates shorthanded to eat, while those who remain on duty shift from sitting to patrol, dipping in and out of rooms at a predictable pace.

Tourists are the irritating variables. Even at noon there are too many of them, lingering. The more popular rooms in the museum display paintings by Rubens himself, but these pieces are too large to safely steal or too somberly religious for Breitwieser's taste. The gallery with Adam and Eve features items Rubens collected during his lifetime, including marble busts of Roman philosophers, a terracotta sculpture of Hercules, and a scattering of Dutch and Italian oil paintings. The ivory itself, by the German carver Georg Petel, was likely received by Rubens as a gift.

As the tourists circle, Breitwieser positions himself in front of an oil painting and assumes an art-gazing stance. Hands on hips, or arms crossed, or chin cupped. His repertoire includes more than a dozen such poses, all meant to connote serene contemplation, even while his heart is revving with excitement and fear. Anne-Catherine hovers near the gallery's doorway, sometimes standing, sometimes sitting on a bench, always with an air of casual indifference, making sure she has a clear view of the hallway beyond. There are no security cameras in the area. There's only a scattered handful in the whole museum, and he has noted that each has a proper wire; occasionally, in smaller museums, they're fake.

A moment soon comes when the couple is alone in the room. The transformation is explosive, a flame to the fuel, as Breitwieser sheds his studious pose and leaps over the security cordon to the wooden dresser. He digs the Swiss Army knife from his pocket, pries open a screwdriver tool, and sets to work on the plexiglass box.

Four turns of the screw, maybe five. The carving to him is a masterpiece, just ten inches tall yet dazzlingly detailed, the first humans gazing at each other as they move to embrace, the serpent coiled around the tree of knowledge behind them, the forbidden fruit picked but not bitten: humanity at the precipice of sin. He hears a soft cough-that's Anne-Catherine-and vaults away from the dresser, light-footed and fluid, and reassumes art-watching mode as a guard appears. The Swiss Army knife is back in his pocket, though the screwdriver is still extended.

The guard walks into the room and stops, then scans the gallery methodically. Breitwieser contains his breathing. The officer turns around and is barely beneath the doorway before the...

Approaching the museum, ready to hunt, Stéphane Breitwieser clasps hands with his girlfriend, Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus, and together they stroll to the front desk and say hello, a cute couple. Then they purchase two tickets with cash and walk in.

It's lunchtime, stealing time, on a busy Sunday in Antwerp, Belgium, in February 1997. The couple blends with the tourists at the Rubens House, pointing and nodding at sculptures and oils. Anne-Catherine is tastefully dressed in Chanel and Dior bought in secondhand shops, a big Yves Saint Laurent bag on her shoulder. Breitwieser wears a button-down shirt tucked into stylish pants, topped by an overcoat that's sized a little too roomy, a Swiss Army knife stashed in a pocket.

The Rubens House is an elegant museum in the former residence of Peter Paul Rubens, the great Flemish painter of the seventeenth century. The couple drifts through the parlor and kitchen and dining room as Breitwieser memorizes the side doors and keeps track of the guards. Several escape routes take shape in his mind. The item they're hunting is sheltered at the rear of the museum, in a ground-floor gallery with a brass chandelier and soaring windows, some now shuttered to protect the works from the midday sun. Here, mounted atop an ornate wooden dresser, is a plexiglass display box fastened to a sturdy base. Sealed inside the box is an ivory sculpture of Adam and Eve.

Breitwieser had encountered the piece on a solo scouting trip a few weeks earlier and had fallen under its spell-the four-hundred-year-old carving still radiates the inner glow, unique to ivory, that feels to him transcendent. After that trip, he could not stop thinking of the sculpture, dreaming of it, so he has returned to the Rubens House with Anne-Catherine.

All forms of security have a weakness. The flaw with the plexiglass box, he had seen on his scouting visit, is that the upper part can be separated from the base by removing two screws. Tricky screws, sure, difficult to reach at the rear of the box, but just two. The flaw with the security guards is they're human. They get hungry. Most of the day, Breitwieser had observed, there is a guard in each gallery, watching from a chair. Except at lunchtime, when the chairs wait empty as the security staff rotates shorthanded to eat, while those who remain on duty shift from sitting to patrol, dipping in and out of rooms at a predictable pace.

Tourists are the irritating variables. Even at noon there are too many of them, lingering. The more popular rooms in the museum display paintings by Rubens himself, but these pieces are too large to safely steal or too somberly religious for Breitwieser's taste. The gallery with Adam and Eve features items Rubens collected during his lifetime, including marble busts of Roman philosophers, a terracotta sculpture of Hercules, and a scattering of Dutch and Italian oil paintings. The ivory itself, by the German carver Georg Petel, was likely received by Rubens as a gift.

As the tourists circle, Breitwieser positions himself in front of an oil painting and assumes an art-gazing stance. Hands on hips, or arms crossed, or chin cupped. His repertoire includes more than a dozen such poses, all meant to connote serene contemplation, even while his heart is revving with excitement and fear. Anne-Catherine hovers near the gallery's doorway, sometimes standing, sometimes sitting on a bench, always with an air of casual indifference, making sure she has a clear view of the hallway beyond. There are no security cameras in the area. There's only a scattered handful in the whole museum, and he has noted that each has a proper wire; occasionally, in smaller museums, they're fake.

A moment soon comes when the couple is alone in the room. The transformation is explosive, a flame to the fuel, as Breitwieser sheds his studious pose and leaps over the security cordon to the wooden dresser. He digs the Swiss Army knife from his pocket, pries open a screwdriver tool, and sets to work on the plexiglass box.

Four turns of the screw, maybe five. The carving to him is a masterpiece, just ten inches tall yet dazzlingly detailed, the first humans gazing at each other as they move to embrace, the serpent coiled around the tree of knowledge behind them, the forbidden fruit picked but not bitten: humanity at the precipice of sin. He hears a soft cough-that's Anne-Catherine-and vaults away from the dresser, light-footed and fluid, and reassumes art-watching mode as a guard appears. The Swiss Army knife is back in his pocket, though the screwdriver is still extended.

The guard walks into the room and stops, then scans the gallery methodically. Breitwieser contains his breathing. The officer turns around and is barely beneath the doorway before the...