Americas

- Publisher : Random House Trade Paperbacks; Reprint edition

- Published : 24 May 2022

- Pages : 352

- ISBN-10 : 1984855115

- ISBN-13 : 9781984855114

- Language : English

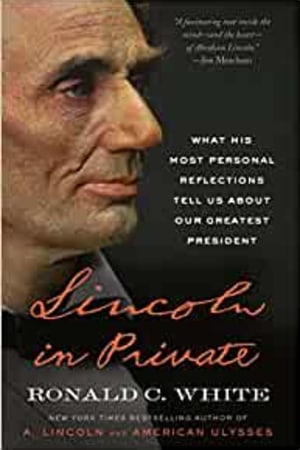

Lincoln in Private: What His Most Personal Reflections Tell Us About Our Greatest President

"An intimate character portrait and fascinating inquiry into the basis of Lincoln's energetic, curious mind."-The Wall Street Journal

WINNER OF THE BARONDESS/LINCOLN AWARD • From the New York Times bestselling author of A. Lincoln and American Ulysses, a revelatory glimpse into the intellectual journey of our sixteenth president through his private notes to himself, explored together here for the first time

A deeply private man, shut off even to those who worked closely with him, Abraham Lincoln often captured "his best thoughts," as he called them, in short notes to himself. He would work out his personal stances on the biggest issues of the day, never expecting anyone to see these frank, unpolished pieces of writing, which he'd then keep close at hand, in desk drawers and even in his top hat. The profound importance of these notes has been overlooked, because the originals are scattered across several different archives and have never before been brought together and examined as a coherent whole.

Now, renowned Lincoln historian Ronald C. White walks readers through twelve of Lincoln's most important private notes, showcasing our greatest president's brilliance and empathy, but also his very human anxieties and ambitions. We look over Lincoln's shoulder as he grapples with the problem of slavery, attempting to find convincing rebuttals to those who supported the evil institution ("As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy."); prepares for his historic debates with Stephen Douglas; expresses his private feelings after a defeated bid for a Senate seat ("With me, the race of ambition has been a failure-a flat failure"); voices his concerns about the new Republican Party's long-term prospects; develops an argument for national unity amidst a secession crisis that would ultimately rend the nation in two; and, for a president many have viewed as not religious, develops a sophisticated theological reflection in the midst of the Civil War ("it is quite possible that God's purpose is something different from the purpose of either party"). Additionally, in a historic first, all 111 Lincoln notes are transcribed in the appendix, a gift to scholars and Lincoln buffs alike.

These are notes Lincoln never expected anyone to read, put into context by a writer who has spent his career studying Lincoln's life and words. The result is a rare glimpse into the mind and soul of one of our nation's most important figures.

WINNER OF THE BARONDESS/LINCOLN AWARD • From the New York Times bestselling author of A. Lincoln and American Ulysses, a revelatory glimpse into the intellectual journey of our sixteenth president through his private notes to himself, explored together here for the first time

A deeply private man, shut off even to those who worked closely with him, Abraham Lincoln often captured "his best thoughts," as he called them, in short notes to himself. He would work out his personal stances on the biggest issues of the day, never expecting anyone to see these frank, unpolished pieces of writing, which he'd then keep close at hand, in desk drawers and even in his top hat. The profound importance of these notes has been overlooked, because the originals are scattered across several different archives and have never before been brought together and examined as a coherent whole.

Now, renowned Lincoln historian Ronald C. White walks readers through twelve of Lincoln's most important private notes, showcasing our greatest president's brilliance and empathy, but also his very human anxieties and ambitions. We look over Lincoln's shoulder as he grapples with the problem of slavery, attempting to find convincing rebuttals to those who supported the evil institution ("As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy."); prepares for his historic debates with Stephen Douglas; expresses his private feelings after a defeated bid for a Senate seat ("With me, the race of ambition has been a failure-a flat failure"); voices his concerns about the new Republican Party's long-term prospects; develops an argument for national unity amidst a secession crisis that would ultimately rend the nation in two; and, for a president many have viewed as not religious, develops a sophisticated theological reflection in the midst of the Civil War ("it is quite possible that God's purpose is something different from the purpose of either party"). Additionally, in a historic first, all 111 Lincoln notes are transcribed in the appendix, a gift to scholars and Lincoln buffs alike.

These are notes Lincoln never expected anyone to read, put into context by a writer who has spent his career studying Lincoln's life and words. The result is a rare glimpse into the mind and soul of one of our nation's most important figures.

Editorial Reviews

"An intimate character portrait and fascinating inquiry into the basis of Lincoln's energetic, curious mind . . . We see in Lincoln's fragments a poised and resolute intellectual. We also see a vulnerable individual humbled by the precariousness of the nation and of its vast, uncertain future. . . . As Mr. White shows so persuasively, Lincoln's quiet, personal moments laid the foundation for his enduring public legacy."-The Wall Street Journal

"These selected personal notes form chapters that describe Lincoln's life in private moments. As a whole, they create a unique, intimate, highly readable, and personable biography of Abraham Lincoln."-New York Journal of Books

"In this elegant and illuminating book, the great biographer Ronald C. White takes us on a fascinating tour inside the mind-and the heart-of Abraham Lincoln. . . . An important and timeless work."-Jon Meacham, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of His Truth Is Marching On

"This engaging volume captures the private thoughts of a man who often still feels like an enigma more than a century and a half after his death. Through insightful analysis, Ronald C. White enables us to better understand Lincoln and to better comprehend how the political and cultural landscape nurtured his thinking. Lincoln in Private is essential reading for both scholars and general audiences alike."-Edna Greene Medford, author of Lincoln and Emancipation

"Out of long-forgotten memoranda, Ronald C. White has managed to construct a major Lincoln study that truly illuminates the life and philosophy of our greatest president. This is an exceptional feat of research, reconstruction, and reanalysis. It deserves a place on every bookshelf alongside Lincoln's collected works and, of course, White's own books."-Harold Holzer, author of Lincoln and the Power of the Press and winner of the Lincoln Prize

"Abraham Lincoln rendered the nation's enduring tensions and purposes in unforgettable prose. Yet Lincoln did some of his best writing in small fragments, personal notes, and memos that illuminate his thinking anew. By assembling and expertly explicating these gems, Ronald C. White has made a singular and valuable contribution to the literature on our greatest president."

"These selected personal notes form chapters that describe Lincoln's life in private moments. As a whole, they create a unique, intimate, highly readable, and personable biography of Abraham Lincoln."-New York Journal of Books

"In this elegant and illuminating book, the great biographer Ronald C. White takes us on a fascinating tour inside the mind-and the heart-of Abraham Lincoln. . . . An important and timeless work."-Jon Meacham, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of His Truth Is Marching On

"This engaging volume captures the private thoughts of a man who often still feels like an enigma more than a century and a half after his death. Through insightful analysis, Ronald C. White enables us to better understand Lincoln and to better comprehend how the political and cultural landscape nurtured his thinking. Lincoln in Private is essential reading for both scholars and general audiences alike."-Edna Greene Medford, author of Lincoln and Emancipation

"Out of long-forgotten memoranda, Ronald C. White has managed to construct a major Lincoln study that truly illuminates the life and philosophy of our greatest president. This is an exceptional feat of research, reconstruction, and reanalysis. It deserves a place on every bookshelf alongside Lincoln's collected works and, of course, White's own books."-Harold Holzer, author of Lincoln and the Power of the Press and winner of the Lincoln Prize

"Abraham Lincoln rendered the nation's enduring tensions and purposes in unforgettable prose. Yet Lincoln did some of his best writing in small fragments, personal notes, and memos that illuminate his thinking anew. By assembling and expertly explicating these gems, Ronald C. White has made a singular and valuable contribution to the literature on our greatest president."

Readers Top Reviews

Nancy A.BekofskeJ.K

Facing protesters over "Mr Lincoln's war," President Lincoln was preparing a reply when a congressman complimented him on so swiftly composing from scratch. Lincoln pointed to an open desk drawer filled with scraps of paper with his "best thoughts on the subject." He explained, "I never let one of those ideas escape me." These private notes and reflections were a valuable resource for the president, and a more valuable exercise for working out and preserving his thoughts. Never meant for public consumption, his notes were open and revealing about his private beliefs and feelings. Some of his notes had been destroyed when he moved from his Illinois home to Washington, D.C. But 109 were found after his death, deposited in a bank vault. Lincoln's secretaries Nicolay and Hay included some of these private notes in their ten volume history. Lincoln in Private by Ronald C. White explores ten of these private notes, contemplating on what we can learn from them about Lincoln. They vary from a lyrical description of encountering Niagara Falls to a mediation on Divine Will in human affairs. Lincoln's ability to logic out arguments comes across in these notes. He was exceedingly well read, delving into newspapers and books from across the country, including pro-slavery sources. He thereby could counter arguments from the opposite political spectrum, understanding their position. White takes readers through a thorough exegesis of each note, putting it in historic context as well as explaining its significance. I am even more impressed by Lincoln. Considering his lack of formal education and rural roots, his depression and life challenges, his genius could not be contained, but, luckily for our country, found its proper application in at our most critical time in history. I received a free galley from the publisher through NetGalley. My review is fair and unbiased.

Paul Aganski

Dr. White brings Lincoln to the reader in a deep and accessible way and God knows we could use a lot of Lincoln especially now.

Sandra W

This approach strips away the influence of the politics of the time leaving you with a real understanding of the person.

robert abbot

I read the entire chapter on Lincoln's thoughts on his ambitions during a depressed time in his life, and I was profitted.

George P. Wood

“Of making many books there is no end,” Ecclesiastes 12:12 says, and nowhere is this truer than of books about Abraham Lincoln. The problem confronting would-be Lincoln authors is that every angle of Lincoln’s life seems to have been covered in exhaustive, not to mention exhausting, detail. Ronald C. White is one of those authors, with three books to his credit already: A. Lincoln (2009), The Eloquent President (2005), and Lincoln’s Greatest Speech (2002). And yet, in Lincoln in Private, White has found a new angle to understanding America’s greatest president—or second greatest if you put George Washington first. That angle comes from the 111 extant notes Lincoln wrote himself over the course of his lifetime. These notes outline his thinking on issues both great and small. He wrote them for himself, not necessarily as the first drafts of subsequent speeches or articles, but as an exercise in knowing his mind on a given topic. In the Appendix, White brings together into one place all 111 notes, which had been previously scattered across the pages of Nicolay and Hay’s 10-volume Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln (1905) and Roy P. Basler’s 11-volume Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (1953–55) and Supplement (1974). These can also be accessed online through the Papers of Abraham Lincoln project. More importantly, White culls 12 of these notes for extended comment. He organizes the notes under three headings, the three main phases of Lincoln’s adult life: Lawyer, Politician, and President. I was aware of two of these notes prior to reading the book: Lincoln’s notes regarding slavery (pp. 47–53, 181–182) and the divine will (pp. 149–160, 261). The former is a reductio ad absurdum of pro-slavery arguments. The latter is a reflection on what providence might be accomplishing in the Civil War, whose logic, though not words, is reflected in the final paragraph of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural. The other 10 notes were new to me. What struck White and will strike the reader is Lincoln’s intellectual curiosity. Whether writing about Niagara Falls, the legal profession, the sectional character of the Republican party, the nature of democracy, pro-slavery theology, or secession, Lincoln strove to understand another person’s beliefs from within that belief system. Precisely because of this empathetic reading, Lincoln was able to respond cogently, concisely, and critically to views opposite his own. Throughout, he demonstrates an ability to get at the basis of an opponent’s argument and refute it. Take his Fragment on Pro-Slavery Theology (pp. 106–116, 221–222), which he wrote in response to Rev. Frederick A. Ross’s Slavery Ordained of God. Lincoln summarizes Ross’s argument this way: “The sum of pro-slavery theology seems to be this: ‘Slavery is not universally right, nor yet universally wrong; it is better for some people to be sl...

Short Excerpt Teaser

Chapter 1

The Lyrical Lincoln: The Transcendence of Niagara Falls

September 25–30, 1848

Niagara-Falls! By what mysterious power is it that millions and millions, are drawn from all parts of the world, to gaze upon Niagara Falls? There is no mystery about the thing itself. Every effect is just such as any intelligent man knowing the causes, would anticipate, without [seeing] it. If the water moving onward in a great river, reaches a point where there is a perpendicular jog, of a hundred feet in descent, in the bottom of the river-it is plain the water will have a violent and continuous plunge at that point. It is also plain the water, thus plunging, will foam, and roar, and send up a mist, continuously, in which last, during sunshine, there will be perpetual rain-bows. The mere physical of Niagara Falls is only this. Yet this is really a very small part of that world's wonder. Its power to excite reflection, and emotion, is its great charm. The geologist will demonstrate that the plunge, or fall, was once at Lake Ontario, and has worn its way back to its present position; he will ascertain how fast it is wearing now, and so get a basis for determining how long it has been wearing back from Lake Ontario, and finally demonstrate by it that this world is at least fourteen thousand years old. A philosopher of a slightly different turn will say Niagara Falls is only the lip of the basin out of which pours all the surplus water which rains down on two or three hundred thousand square miles of the earth's surface. He will estimate [with] approximate accuracy, that five hundred thousand [to]ns of water, falls with its full weight, a distance of a hundred feet each minute-thus exerting a force equal to the lifting of the same weight, through the same space, in the same time. And then the further reflection comes that this vast amount of water, constantly pouring down, is supplied by an equal amount constantly lifted up, by the sun; and still he says, "If this much is lifted up for this one space of two or three hundred thousand square miles, an equal amount must be lifted for every other equal space, and he is overwhelmed in the contemplation of the vast power the sun is constantly exerting in quiet, noiseless operation of lifting water up to be rained down again.

But still there is more. It calls up the indefinite past. When Columbus first sought this continent-when Christ suffered on the cross-when Moses led Israel through the Red-Sea-nay, even, when Adam first came from the hand of his Maker-then as now, Niagara was roaring here. The eyes of that species of extinct giants, whose bones fill the mounds of America, have gazed on Niagara, as ours do now. Co[n]temporary with the whole race of men, and older than the first man, Niagara is strong, and fresh to-day as ten thousand years ago. The Mammoth and Mastodon-now so long dead, that fragments of their monstrous bones, alone testify, that they ever lived, have gazed on Niagara. In that long-long time, never still for a single moment. Never dried, never froze, never slept, never rested.

The train carrying the Lincoln family from Buffalo to Niagara Falls passed close enough to the river for them to glimpse its white-peaked rapids and hear its roar as it surged to the falls. Arriving at the small village on the American side of the falls in late September 1848, Lincoln, then one year into his congressional term as a representative for Illinois, his wife, Mary, and their two small sons, Robert and Eddy, checked into a tourist hotel.

Like many nineteenth-century tourists, Lincoln probably purchased Oliver G. Steele's popular pocket-sized guidebook, Steele's Book of Niagara Falls, then in its tenth edition. Steele, a successful Buffalo businessman, was serving as that city's first superintendent of public schools.

Sometime in the afternoon, they boarded a carriage and crossed the three-hundred-foot bridge to Bath Island to register at the tollbooth, where Lincoln paid the price of admission of twenty-five cents for full access to the falls area for up to a year.

The young family probably then strolled along a gravel path under the yellow and scarlet fall foliage of elm, ash, and maple trees, heading toward the thunderous roar of the waters of the Great Lakes as they plummeted 167 feet into a deep, surging pool.

Suddenly, there it was: Niagara Falls.

Lincoln's visit to Niagara Falls prompted him to write his most lyrical surviving fragment. Captivated by America's preeminent natural wonder of his day, his intellectual curiosity shines through in this private piece of writing. This reflection expresses ...

The Lyrical Lincoln: The Transcendence of Niagara Falls

September 25–30, 1848

Niagara-Falls! By what mysterious power is it that millions and millions, are drawn from all parts of the world, to gaze upon Niagara Falls? There is no mystery about the thing itself. Every effect is just such as any intelligent man knowing the causes, would anticipate, without [seeing] it. If the water moving onward in a great river, reaches a point where there is a perpendicular jog, of a hundred feet in descent, in the bottom of the river-it is plain the water will have a violent and continuous plunge at that point. It is also plain the water, thus plunging, will foam, and roar, and send up a mist, continuously, in which last, during sunshine, there will be perpetual rain-bows. The mere physical of Niagara Falls is only this. Yet this is really a very small part of that world's wonder. Its power to excite reflection, and emotion, is its great charm. The geologist will demonstrate that the plunge, or fall, was once at Lake Ontario, and has worn its way back to its present position; he will ascertain how fast it is wearing now, and so get a basis for determining how long it has been wearing back from Lake Ontario, and finally demonstrate by it that this world is at least fourteen thousand years old. A philosopher of a slightly different turn will say Niagara Falls is only the lip of the basin out of which pours all the surplus water which rains down on two or three hundred thousand square miles of the earth's surface. He will estimate [with] approximate accuracy, that five hundred thousand [to]ns of water, falls with its full weight, a distance of a hundred feet each minute-thus exerting a force equal to the lifting of the same weight, through the same space, in the same time. And then the further reflection comes that this vast amount of water, constantly pouring down, is supplied by an equal amount constantly lifted up, by the sun; and still he says, "If this much is lifted up for this one space of two or three hundred thousand square miles, an equal amount must be lifted for every other equal space, and he is overwhelmed in the contemplation of the vast power the sun is constantly exerting in quiet, noiseless operation of lifting water up to be rained down again.

But still there is more. It calls up the indefinite past. When Columbus first sought this continent-when Christ suffered on the cross-when Moses led Israel through the Red-Sea-nay, even, when Adam first came from the hand of his Maker-then as now, Niagara was roaring here. The eyes of that species of extinct giants, whose bones fill the mounds of America, have gazed on Niagara, as ours do now. Co[n]temporary with the whole race of men, and older than the first man, Niagara is strong, and fresh to-day as ten thousand years ago. The Mammoth and Mastodon-now so long dead, that fragments of their monstrous bones, alone testify, that they ever lived, have gazed on Niagara. In that long-long time, never still for a single moment. Never dried, never froze, never slept, never rested.

The train carrying the Lincoln family from Buffalo to Niagara Falls passed close enough to the river for them to glimpse its white-peaked rapids and hear its roar as it surged to the falls. Arriving at the small village on the American side of the falls in late September 1848, Lincoln, then one year into his congressional term as a representative for Illinois, his wife, Mary, and their two small sons, Robert and Eddy, checked into a tourist hotel.

Like many nineteenth-century tourists, Lincoln probably purchased Oliver G. Steele's popular pocket-sized guidebook, Steele's Book of Niagara Falls, then in its tenth edition. Steele, a successful Buffalo businessman, was serving as that city's first superintendent of public schools.

Sometime in the afternoon, they boarded a carriage and crossed the three-hundred-foot bridge to Bath Island to register at the tollbooth, where Lincoln paid the price of admission of twenty-five cents for full access to the falls area for up to a year.

The young family probably then strolled along a gravel path under the yellow and scarlet fall foliage of elm, ash, and maple trees, heading toward the thunderous roar of the waters of the Great Lakes as they plummeted 167 feet into a deep, surging pool.

Suddenly, there it was: Niagara Falls.

Lincoln's visit to Niagara Falls prompted him to write his most lyrical surviving fragment. Captivated by America's preeminent natural wonder of his day, his intellectual curiosity shines through in this private piece of writing. This reflection expresses ...