Cooking Education & Reference

- Publisher : Clarkson Potter

- Published : 03 May 2022

- Pages : 304

- ISBN-10 : 0593138708

- ISBN-13 : 9780593138700

- Language : English

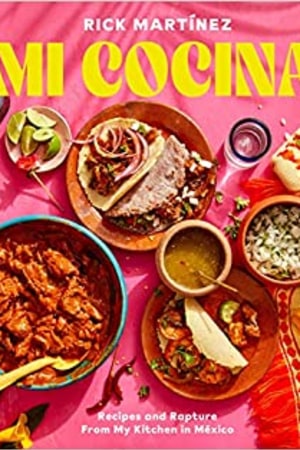

Mi Cocina: Recipes and Rapture from My Kitchen in Mexico: A Cookbook

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • A highly personal love letter to the beauty and bounty of México in more than 100 transportive recipes, from the beloved food writer and host of the Babish Culinary Universe show Pruébalo on YouTube and Food52's Sweet Heat

"This intimate look at a country's cuisine has as much spice as it does soul."-Publishers Weekly (starred review)

ONE OF THE MOST ANTICIPATED COOKBOOKS OF 2022-Time, Food52

Join Rick Martínez on a once-in-a-lifetime culinary journey throughout México that begins in Mexico City and continues through 32 states, in 156 cities, and across 20,000 incredibly delicious miles. In Mi Cocina, Rick shares deeply personal recipes as he re-creates the dishes and specialties he tasted throughout his journey. Inspired by his travels, the recipes are based on his taste memories and experiences. True to his spirit and reflective of his deep connections with people and places, these dishes will revitalize your pantry and transform your cooking repertoire.

Highlighting the diversity, richness, and complexity of Mexican cuisine, he includes recipes like herb and cheese meatballs bathed in a smoky, spicy chipotle sauce from Oaxaca called Albóndigas en Chipotle; northern México's grilled Carne Asada that he stuffs into a grilled quesadilla for full-on cheesy-meaty food euphoria; and tender sweet corn tamales packed with succulent shrimp, chiles, and roasted tomatoes from Sinaloa on the west coast. Rick's poignant essays throughout lend context-both personal and cultural-to quilt together a story that is rich and beautiful, touching and insightful.

"This intimate look at a country's cuisine has as much spice as it does soul."-Publishers Weekly (starred review)

ONE OF THE MOST ANTICIPATED COOKBOOKS OF 2022-Time, Food52

Join Rick Martínez on a once-in-a-lifetime culinary journey throughout México that begins in Mexico City and continues through 32 states, in 156 cities, and across 20,000 incredibly delicious miles. In Mi Cocina, Rick shares deeply personal recipes as he re-creates the dishes and specialties he tasted throughout his journey. Inspired by his travels, the recipes are based on his taste memories and experiences. True to his spirit and reflective of his deep connections with people and places, these dishes will revitalize your pantry and transform your cooking repertoire.

Highlighting the diversity, richness, and complexity of Mexican cuisine, he includes recipes like herb and cheese meatballs bathed in a smoky, spicy chipotle sauce from Oaxaca called Albóndigas en Chipotle; northern México's grilled Carne Asada that he stuffs into a grilled quesadilla for full-on cheesy-meaty food euphoria; and tender sweet corn tamales packed with succulent shrimp, chiles, and roasted tomatoes from Sinaloa on the west coast. Rick's poignant essays throughout lend context-both personal and cultural-to quilt together a story that is rich and beautiful, touching and insightful.

Readers Top Reviews

banderwiessmaria

This is one of the best Mexican cookbooks I've seen. It has everything from every local. Bravo rick!

Sylvie C.banderwi

Blown away by this cookbook - it will easily be named best cookbook of the year. Because of Rick's masterful storytelling to the bright, beautiful recipes that take you across Mexico, I am more excited to cook out of this cookbook than any I've read this year. I literally hugged it a few times while reading the salsa section. I'm headed to the Mexican market today to pick up some exciting new ingredients I haven't cooked with before, and honestly i've wanted to cook 90% of the recipes I've read so far (and I'm about halfway through the book). I couldn't put it down - it read to me like an exciting novel. Congratulations Rick on such a work of art.

AMTAMTSylvie C.ba

This is very well written, Rick has a way with words and I couldn’t put it down before reading through all his essays. I have tried many of his recipes in the past and they are always delicious. I hope he writes more books in the future.

Jane MiricAMTAMTS

An overall great resource. Recipes are clearly written, well explained, and so far, outcomes have been delish. Plan to prepare at least one recipe per week. I’m learning soo much!

miraduJane MiricA

The book is full of fun bright colors and photography - it brings a smile to your face as you contemplate which delicious dish to make. The recipes are easy to follow and Rick shares his own stories of how and why they came into this book. Instant cookbook classic.

Short Excerpt Teaser

Introduction

When I was growing up in Austin, Texas, my mom and I spent a lot of time watching cooking shows. I'd stretch out on the hideous gold plaid sofa in front of our rear-projection big-screen TV (that took up half of the living room) and Mom would watch from the kitchen, usually while sweeping the floor with one of the superior Mexican brooms she'd buy across the border and bring home.

We loved Two Fat Ladies on the BBC and Emeril Live, but our favorite show was Diana Kennedy 's. We'd watch her make chorizo with green and red chiles from a mercado in Michoacán, and were deeply envious of her sundrenched kitchen full of red clay bowls. It all just seemed so magical. And dammit, I wanted all of those things, too! I decided then and there that I would grow up to be just like her.

Now I know that this desire was masking a deeper one: the desire to understand myself. Sure, part of me wanted the ego recognition of being "the best" or "the authority," but what was so devastating to me as a Mexican American boy growing up in Texas was that she knew more about my culture and my people than I did. That a British woman and Rick Bayless, a white man from Oklahoma, got to represent the culinary diversity of México while my Mexican American family tried to enculturate with meatloaf and Chef Boyardee.

My gread-grandfather Andrés Castruita was a dairy farmer in Torreón, a city in the northern state of Coahuila. He sold his farm in 1910, moved his family, including my five-yearold grandfather Agustín Flores Castruita, across the border and bought a small farm just south of Austin. Even though my grandfather only spent the first five years of his life in México, somehow, he was able to hold on to it-from the intense sea-green color of his house to his embellished style of handwriting to the mariachi songs he'd sing when he drank. I didn't know at the time how Mexican all these things were, but in the years since, as I've explored the country myself, I've recognized them all. To this day, I'm not sure how he picked them up from such a young age.

Agustín would grow up in Austin, eventually marry and have five children, the first of whom was my mom, Gloria. While he wasn't the best father in the world (he had a tendency to play favorites), he was a good grandfather. He liked me, probably because I looked like him. I have a lot of the Castruita features, but more important, I am dark, like he was. My mom, dad, and brother are all light-complected. When I was born, the nurse who delivered me said to my mom, "Gloria, your baby has a tan!"

From that moment on, I was different. I didn't want to be, but I had no choice. I was brown, and in Texas in the 1970s that meant you were labeled Mexican. Neither of those things-being brown and being Mexican-was bad to me, but to many of the parents, students, and teachers at the all-white preschool and elementary school in a small town south of Austin (where I was the first Mexican American to attend and my younger brother was the second), they were bad. So my parents decided not to teach us Spanish as kids because they were worried we'd develop accents and would be made fun of or be held back in school as a result.

When I was in first grade, the school administration tried to put me in the free-lunch program. Both my parents worked; we were middle class; we had a swimming pool and lake property. But the assumption was that I needed it. When I was in second grade, the PTA tried to start a coat collection for me. I had two coats; they were new and both fit well. I didn't need more coats. But the assumption was that I needed it. When I was in third grade, my homeroom teacher asked the class what we wanted to be when we grew up. I eagerly raised my hand and said I wanted to be President of the United States. The little boy who sat next to me looked me in the eye. "You can't be President," he said. "You're not white." I was so confused. I didn't understand. I went home that night and asked my parents and they said he was wrong; as an American-born citizen, I had every right to be president. But that eight-yearold boy was taught that I couldn't be. Someone he trusted said those words to him. And his assumption was that I needed to hear them.

Back when my parents bought their first home in Austin in 1963, the neighborhood association called a vote on whether to allow them, a Mexican American couple, into the community or not. Eleven years later, they were forced to finance their second home on their own because no mortgage company would lend money to a Mexican American family wanting to build a custom-home in an all...

When I was growing up in Austin, Texas, my mom and I spent a lot of time watching cooking shows. I'd stretch out on the hideous gold plaid sofa in front of our rear-projection big-screen TV (that took up half of the living room) and Mom would watch from the kitchen, usually while sweeping the floor with one of the superior Mexican brooms she'd buy across the border and bring home.

We loved Two Fat Ladies on the BBC and Emeril Live, but our favorite show was Diana Kennedy 's. We'd watch her make chorizo with green and red chiles from a mercado in Michoacán, and were deeply envious of her sundrenched kitchen full of red clay bowls. It all just seemed so magical. And dammit, I wanted all of those things, too! I decided then and there that I would grow up to be just like her.

Now I know that this desire was masking a deeper one: the desire to understand myself. Sure, part of me wanted the ego recognition of being "the best" or "the authority," but what was so devastating to me as a Mexican American boy growing up in Texas was that she knew more about my culture and my people than I did. That a British woman and Rick Bayless, a white man from Oklahoma, got to represent the culinary diversity of México while my Mexican American family tried to enculturate with meatloaf and Chef Boyardee.

My gread-grandfather Andrés Castruita was a dairy farmer in Torreón, a city in the northern state of Coahuila. He sold his farm in 1910, moved his family, including my five-yearold grandfather Agustín Flores Castruita, across the border and bought a small farm just south of Austin. Even though my grandfather only spent the first five years of his life in México, somehow, he was able to hold on to it-from the intense sea-green color of his house to his embellished style of handwriting to the mariachi songs he'd sing when he drank. I didn't know at the time how Mexican all these things were, but in the years since, as I've explored the country myself, I've recognized them all. To this day, I'm not sure how he picked them up from such a young age.

Agustín would grow up in Austin, eventually marry and have five children, the first of whom was my mom, Gloria. While he wasn't the best father in the world (he had a tendency to play favorites), he was a good grandfather. He liked me, probably because I looked like him. I have a lot of the Castruita features, but more important, I am dark, like he was. My mom, dad, and brother are all light-complected. When I was born, the nurse who delivered me said to my mom, "Gloria, your baby has a tan!"

From that moment on, I was different. I didn't want to be, but I had no choice. I was brown, and in Texas in the 1970s that meant you were labeled Mexican. Neither of those things-being brown and being Mexican-was bad to me, but to many of the parents, students, and teachers at the all-white preschool and elementary school in a small town south of Austin (where I was the first Mexican American to attend and my younger brother was the second), they were bad. So my parents decided not to teach us Spanish as kids because they were worried we'd develop accents and would be made fun of or be held back in school as a result.

When I was in first grade, the school administration tried to put me in the free-lunch program. Both my parents worked; we were middle class; we had a swimming pool and lake property. But the assumption was that I needed it. When I was in second grade, the PTA tried to start a coat collection for me. I had two coats; they were new and both fit well. I didn't need more coats. But the assumption was that I needed it. When I was in third grade, my homeroom teacher asked the class what we wanted to be when we grew up. I eagerly raised my hand and said I wanted to be President of the United States. The little boy who sat next to me looked me in the eye. "You can't be President," he said. "You're not white." I was so confused. I didn't understand. I went home that night and asked my parents and they said he was wrong; as an American-born citizen, I had every right to be president. But that eight-yearold boy was taught that I couldn't be. Someone he trusted said those words to him. And his assumption was that I needed to hear them.

Back when my parents bought their first home in Austin in 1963, the neighborhood association called a vote on whether to allow them, a Mexican American couple, into the community or not. Eleven years later, they were forced to finance their second home on their own because no mortgage company would lend money to a Mexican American family wanting to build a custom-home in an all...