Performing Arts

- Publisher : Random House

- Published : 01 Nov 2022

- Pages : 784

- ISBN-10 : 0812994302

- ISBN-13 : 9780812994308

- Language : English

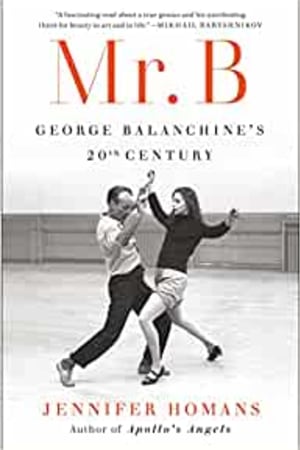

Mr. B: George Balanchine's 20th Century

"A fascinating read about a true genius and his unrelenting thirst for beauty in art and in life."-MIKHAIL BARYSHNIKOV

Based on a decade of unprecedented research, the first major biography of George Balanchine, a broad-canvas portrait set against the backdrop of the tumultuous century that shaped the man The New York Times called "the Shakespeare of dancing"-from the bestselling author of Apollo's Angels

Arguably the greatest choreographer who ever lived, George Balanchine was one of the cultural titans of the twentieth century-The New York Times called him "the Shakespeare of dancing." His radical approach to choreography-and life-reinvented the art of ballet and made him a legend. Written with enormous style and artistry, and based on more than one hundred interviews and research in archives across Russia, Europe, and the Americas, Mr. B carries us through Balanchine's tumultuous and high-pitched life story and into the making of his extraordinary dances.

Balanchine's life intersected with some of the biggest historical events of his century. Born in Russia under the last czar, Balanchine experienced the upheavals of World War I, the Russian Revolution, exile, World War II, and the Cold War. A co-founder of the New York City Ballet, he pressed ballet in America to the forefront of modernism and made it a popular art. None of this was easy, and we see his loneliness and failures, his five marriages-all to dancers-and many loves. We follow his bouts of ill health and spiritual crises, and learn of his profound musical skills and sensibility and his immense determination to make some of the most glorious, strange, and beautiful dances ever to grace the modern stage.

With full access to Balanchine's papers and many of his dancers, Jennifer Homans, the dance critic for The New Yorker and a former dancer herself, has spent more than a decade researching Balanchine's life and times to write a vast history of the twentieth century through the lens of one of its greatest artists: the definitive biography of the man his dancers called Mr. B.

Based on a decade of unprecedented research, the first major biography of George Balanchine, a broad-canvas portrait set against the backdrop of the tumultuous century that shaped the man The New York Times called "the Shakespeare of dancing"-from the bestselling author of Apollo's Angels

Arguably the greatest choreographer who ever lived, George Balanchine was one of the cultural titans of the twentieth century-The New York Times called him "the Shakespeare of dancing." His radical approach to choreography-and life-reinvented the art of ballet and made him a legend. Written with enormous style and artistry, and based on more than one hundred interviews and research in archives across Russia, Europe, and the Americas, Mr. B carries us through Balanchine's tumultuous and high-pitched life story and into the making of his extraordinary dances.

Balanchine's life intersected with some of the biggest historical events of his century. Born in Russia under the last czar, Balanchine experienced the upheavals of World War I, the Russian Revolution, exile, World War II, and the Cold War. A co-founder of the New York City Ballet, he pressed ballet in America to the forefront of modernism and made it a popular art. None of this was easy, and we see his loneliness and failures, his five marriages-all to dancers-and many loves. We follow his bouts of ill health and spiritual crises, and learn of his profound musical skills and sensibility and his immense determination to make some of the most glorious, strange, and beautiful dances ever to grace the modern stage.

With full access to Balanchine's papers and many of his dancers, Jennifer Homans, the dance critic for The New Yorker and a former dancer herself, has spent more than a decade researching Balanchine's life and times to write a vast history of the twentieth century through the lens of one of its greatest artists: the definitive biography of the man his dancers called Mr. B.

Editorial Reviews

Chapter 1

Happy Families

When Georgi was born one cold January day in 1904, he was his mother's first illegitimate son. It was official: he was number 160 on the list of newborns at the Church of the Nativity on the Sands in St. Petersburg, where Maria Nikolaevna Vasil'eva had dutifully registered his arrival. On this critical document establishing Balanchine's existence in the eyes of God and the Russian state, his father was absent, and his mother, the authorities noted in a neat hand, was Orthodox but "unwed." The problem was not only that Balanchine came into the world in a half-fallen bastard state, somehow discredited from the start; it was also that without a father, Georgi had no patronymic, and without a patronymic his entire genealogy was in doubt. Who was he, even?

His older sister, Tamara, born two years earlier, was illegitimate too. Ditto his brother, Andrei, who came a year after Georgi, in 1905. On Tamara's document, "ILLEGITIMATE" was even scrawled like a scarlet letter in bold capitals under her name. Had Maria's children been born in Western Europe, they might have held some rights through their mother, but this was Russia, and children automatically took the legal status of their father. The sad fact was that without a paterfamilias none of them had any legal standing at all. They hardly existed. There was only one way back into the social and political fold: in special cases, usually with influence and money changing hands, a child might be legitimized ex post facto by imperial consent and the word of the czar himself.

A cramped note in new ink amending Tamara's, Georgi's, and Andrei's birth documents tells us that this is exactly what happened. On March 18, 1906, the district court legitimized the birth of each of Maria's three children, and on September 23, the Church recognized this change in status too. It was all verified, for anyone who cared to look, in document no. 13025. When Georgi was later asked for his birth certificate, he was able to present an official dictum-Birth Certificate no. 5055-grandly stating that by imperial decree at the St. Petersburg County Court of the Seventh District and acting on a decision from March 18, 1906, it was hereby affirmed that Georgi Melitonovich Balanchivadze had in fact been born to legally wedded parents, both of the Orthodox Christian faith and both married for the first time. His father, it was proclaimed, was the "Hereditary Honorable Citizen Meliton Antonovich Balanchivadze." Stamps, signatures, office duties paid.

This administrative sleight of hand may have normalized Balanchine's birth, but it did nothing to change the facts. If Georgi's parents ever did formally marry-no record has been found-it was not, at least in Meliton's case, for the first...

Happy Families

When Georgi was born one cold January day in 1904, he was his mother's first illegitimate son. It was official: he was number 160 on the list of newborns at the Church of the Nativity on the Sands in St. Petersburg, where Maria Nikolaevna Vasil'eva had dutifully registered his arrival. On this critical document establishing Balanchine's existence in the eyes of God and the Russian state, his father was absent, and his mother, the authorities noted in a neat hand, was Orthodox but "unwed." The problem was not only that Balanchine came into the world in a half-fallen bastard state, somehow discredited from the start; it was also that without a father, Georgi had no patronymic, and without a patronymic his entire genealogy was in doubt. Who was he, even?

His older sister, Tamara, born two years earlier, was illegitimate too. Ditto his brother, Andrei, who came a year after Georgi, in 1905. On Tamara's document, "ILLEGITIMATE" was even scrawled like a scarlet letter in bold capitals under her name. Had Maria's children been born in Western Europe, they might have held some rights through their mother, but this was Russia, and children automatically took the legal status of their father. The sad fact was that without a paterfamilias none of them had any legal standing at all. They hardly existed. There was only one way back into the social and political fold: in special cases, usually with influence and money changing hands, a child might be legitimized ex post facto by imperial consent and the word of the czar himself.

A cramped note in new ink amending Tamara's, Georgi's, and Andrei's birth documents tells us that this is exactly what happened. On March 18, 1906, the district court legitimized the birth of each of Maria's three children, and on September 23, the Church recognized this change in status too. It was all verified, for anyone who cared to look, in document no. 13025. When Georgi was later asked for his birth certificate, he was able to present an official dictum-Birth Certificate no. 5055-grandly stating that by imperial decree at the St. Petersburg County Court of the Seventh District and acting on a decision from March 18, 1906, it was hereby affirmed that Georgi Melitonovich Balanchivadze had in fact been born to legally wedded parents, both of the Orthodox Christian faith and both married for the first time. His father, it was proclaimed, was the "Hereditary Honorable Citizen Meliton Antonovich Balanchivadze." Stamps, signatures, office duties paid.

This administrative sleight of hand may have normalized Balanchine's birth, but it did nothing to change the facts. If Georgi's parents ever did formally marry-no record has been found-it was not, at least in Meliton's case, for the first...

Short Excerpt Teaser

Chapter 1

Happy Families

When Georgi was born one cold January day in 1904, he was his mother's first illegitimate son. It was official: he was number 160 on the list of newborns at the Church of the Nativity on the Sands in St. Petersburg, where Maria Nikolaevna Vasil'eva had dutifully registered his arrival. On this critical document establishing Balanchine's existence in the eyes of God and the Russian state, his father was absent, and his mother, the authorities noted in a neat hand, was Orthodox but "unwed." The problem was not only that Balanchine came into the world in a half-fallen bastard state, somehow discredited from the start; it was also that without a father, Georgi had no patronymic, and without a patronymic his entire genealogy was in doubt. Who was he, even?

His older sister, Tamara, born two years earlier, was illegitimate too. Ditto his brother, Andrei, who came a year after Georgi, in 1905. On Tamara's document, "ILLEGITIMATE" was even scrawled like a scarlet letter in bold capitals under her name. Had Maria's children been born in Western Europe, they might have held some rights through their mother, but this was Russia, and children automatically took the legal status of their father. The sad fact was that without a paterfamilias none of them had any legal standing at all. They hardly existed. There was only one way back into the social and political fold: in special cases, usually with influence and money changing hands, a child might be legitimized ex post facto by imperial consent and the word of the czar himself.

A cramped note in new ink amending Tamara's, Georgi's, and Andrei's birth documents tells us that this is exactly what happened. On March 18, 1906, the district court legitimized the birth of each of Maria's three children, and on September 23, the Church recognized this change in status too. It was all verified, for anyone who cared to look, in document no. 13025. When Georgi was later asked for his birth certificate, he was able to present an official dictum-Birth Certificate no. 5055-grandly stating that by imperial decree at the St. Petersburg County Court of the Seventh District and acting on a decision from March 18, 1906, it was hereby affirmed that Georgi Melitonovich Balanchivadze had in fact been born to legally wedded parents, both of the Orthodox Christian faith and both married for the first time. His father, it was proclaimed, was the "Hereditary Honorable Citizen Meliton Antonovich Balanchivadze." Stamps, signatures, office duties paid.

This administrative sleight of hand may have normalized Balanchine's birth, but it did nothing to change the facts. If Georgi's parents ever did formally marry-no record has been found-it was not, at least in Meliton's case, for the first time. When Georgi and his siblings were born, Meliton had a whole other family: a wife and two children back in his native Georgia. Many years later, Balanchine would wistfully tell his first biographer that this unnamed and faceless first wife, whom he never met, had died and that his father had been a widower-but she hadn't, and he wasn't.

The matter was serious, if not unusual. There were growing numbers of illegitimate children in St. Petersburg in these years, as peasant women, scarves wrapped tightly around their heads and carrying their belongings, fled their villages for new opportunities in nearby urban centers. Marital traditions loosened their hold on these and other urban mothers-townswomen, craftswomen, women filling jobs in businesses and factories, Georgi's mother perhaps among them, who found themselves at once independent and vulnerable in new ways. Official shelters, called "angel factories," even paid two rubles per head for abandoned babies in an effort to absorb the increase in children left by their often struggling and unwed mothers. Even for those with the advantages of rank or wealth, the consequences could be serious: illegitimacy precluded the inheritance of family wealth-Pierre's problem in the early pages of Tolstoy's War and Peace; Alexander Herzen's problem in life. Wealth was not a Balanchivadze problem, at least for now, and nobility was out of the question. "If you are noble," Balanchine later said, "you always want to find out where you come from, my French so and so, my mother was so and so. . . . But they were simple people, nothing, not important."

And so at the moment of birth, there were already complications, uncertainties, revisions, and pasts that would never quite reveal themselves fully or that later took on the aura of secrets and blank spaces in his mind. Balanchine may not have cared that he was officially illegitimate or known that his parents later maneuvered to "correct" the record, but it was a fact ...

Happy Families

When Georgi was born one cold January day in 1904, he was his mother's first illegitimate son. It was official: he was number 160 on the list of newborns at the Church of the Nativity on the Sands in St. Petersburg, where Maria Nikolaevna Vasil'eva had dutifully registered his arrival. On this critical document establishing Balanchine's existence in the eyes of God and the Russian state, his father was absent, and his mother, the authorities noted in a neat hand, was Orthodox but "unwed." The problem was not only that Balanchine came into the world in a half-fallen bastard state, somehow discredited from the start; it was also that without a father, Georgi had no patronymic, and without a patronymic his entire genealogy was in doubt. Who was he, even?

His older sister, Tamara, born two years earlier, was illegitimate too. Ditto his brother, Andrei, who came a year after Georgi, in 1905. On Tamara's document, "ILLEGITIMATE" was even scrawled like a scarlet letter in bold capitals under her name. Had Maria's children been born in Western Europe, they might have held some rights through their mother, but this was Russia, and children automatically took the legal status of their father. The sad fact was that without a paterfamilias none of them had any legal standing at all. They hardly existed. There was only one way back into the social and political fold: in special cases, usually with influence and money changing hands, a child might be legitimized ex post facto by imperial consent and the word of the czar himself.

A cramped note in new ink amending Tamara's, Georgi's, and Andrei's birth documents tells us that this is exactly what happened. On March 18, 1906, the district court legitimized the birth of each of Maria's three children, and on September 23, the Church recognized this change in status too. It was all verified, for anyone who cared to look, in document no. 13025. When Georgi was later asked for his birth certificate, he was able to present an official dictum-Birth Certificate no. 5055-grandly stating that by imperial decree at the St. Petersburg County Court of the Seventh District and acting on a decision from March 18, 1906, it was hereby affirmed that Georgi Melitonovich Balanchivadze had in fact been born to legally wedded parents, both of the Orthodox Christian faith and both married for the first time. His father, it was proclaimed, was the "Hereditary Honorable Citizen Meliton Antonovich Balanchivadze." Stamps, signatures, office duties paid.

This administrative sleight of hand may have normalized Balanchine's birth, but it did nothing to change the facts. If Georgi's parents ever did formally marry-no record has been found-it was not, at least in Meliton's case, for the first time. When Georgi and his siblings were born, Meliton had a whole other family: a wife and two children back in his native Georgia. Many years later, Balanchine would wistfully tell his first biographer that this unnamed and faceless first wife, whom he never met, had died and that his father had been a widower-but she hadn't, and he wasn't.

The matter was serious, if not unusual. There were growing numbers of illegitimate children in St. Petersburg in these years, as peasant women, scarves wrapped tightly around their heads and carrying their belongings, fled their villages for new opportunities in nearby urban centers. Marital traditions loosened their hold on these and other urban mothers-townswomen, craftswomen, women filling jobs in businesses and factories, Georgi's mother perhaps among them, who found themselves at once independent and vulnerable in new ways. Official shelters, called "angel factories," even paid two rubles per head for abandoned babies in an effort to absorb the increase in children left by their often struggling and unwed mothers. Even for those with the advantages of rank or wealth, the consequences could be serious: illegitimacy precluded the inheritance of family wealth-Pierre's problem in the early pages of Tolstoy's War and Peace; Alexander Herzen's problem in life. Wealth was not a Balanchivadze problem, at least for now, and nobility was out of the question. "If you are noble," Balanchine later said, "you always want to find out where you come from, my French so and so, my mother was so and so. . . . But they were simple people, nothing, not important."

And so at the moment of birth, there were already complications, uncertainties, revisions, and pasts that would never quite reveal themselves fully or that later took on the aura of secrets and blank spaces in his mind. Balanchine may not have cared that he was officially illegitimate or known that his parents later maneuvered to "correct" the record, but it was a fact ...