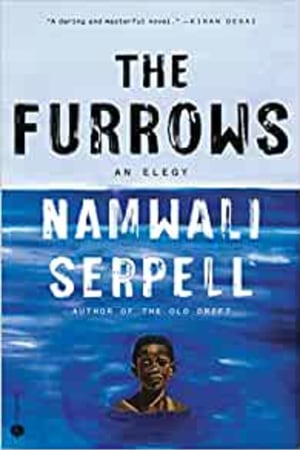

Genre Fiction

- Publisher : Hogarth

- Published : 27 Sep 2022

- Pages : 288

- ISBN-10 : 059344891X

- ISBN-13 : 9780593448915

- Language : English

The Furrows: A Novel

How do you grieve an absence? From the award-winning author of The Old Drift, "a piercing, sharply written novel about the conjuring power of loss" (Raven Leilani, author of Luster).

"A genuine tour de force . . . What seems at first a meditation on family trauma unfolds through the urgency of an amnesiac puzzle-thriller, then a violently compelling love story."-Jonathan Lethem, author of Motherless Brooklyn

ONE OF THE MOST ANTICIPATED BOOKS OF 2022-Vulture, Esquire, Lit Hub, Electric Lit, BookPage

I don't want to tell you what happened. I want to tell you how it felt.

Cassandra Williams is twelve; her little brother, Wayne, is seven. One day, when they're alone together, there is an accident and Wayne is lost forever. His body is never recovered. The missing boy cleaves the family with doubt. Their father leaves, starts another family elsewhere. But their mother can't give up hope and launches an organization dedicated to missing children.

As C grows older, she sees her brother everywhere: in bistros, airplane aisles, subway cars. Here is her brother's face, the light in his eyes, the way he seems to recognize her, too. But it can't be, of course. Or can it? Then one day, in another accident, C meets a man both mysterious and familiar, a man who is also searching for someone and for his own place in the world. His name is Wayne.

Namwali Serpell's remarkable new novel captures the uncanny experience of grief, the way the past breaks over the present like waves in the sea. The Furrows is a bold exploration of memory and mourning that twists unexpectedly into a story of mistaken identity, double consciousness, and the wishful-and sometimes willful-longing for reunion with those we've lost.

"A genuine tour de force . . . What seems at first a meditation on family trauma unfolds through the urgency of an amnesiac puzzle-thriller, then a violently compelling love story."-Jonathan Lethem, author of Motherless Brooklyn

ONE OF THE MOST ANTICIPATED BOOKS OF 2022-Vulture, Esquire, Lit Hub, Electric Lit, BookPage

I don't want to tell you what happened. I want to tell you how it felt.

Cassandra Williams is twelve; her little brother, Wayne, is seven. One day, when they're alone together, there is an accident and Wayne is lost forever. His body is never recovered. The missing boy cleaves the family with doubt. Their father leaves, starts another family elsewhere. But their mother can't give up hope and launches an organization dedicated to missing children.

As C grows older, she sees her brother everywhere: in bistros, airplane aisles, subway cars. Here is her brother's face, the light in his eyes, the way he seems to recognize her, too. But it can't be, of course. Or can it? Then one day, in another accident, C meets a man both mysterious and familiar, a man who is also searching for someone and for his own place in the world. His name is Wayne.

Namwali Serpell's remarkable new novel captures the uncanny experience of grief, the way the past breaks over the present like waves in the sea. The Furrows is a bold exploration of memory and mourning that twists unexpectedly into a story of mistaken identity, double consciousness, and the wishful-and sometimes willful-longing for reunion with those we've lost.

Editorial Reviews

1

≈≈≈

I don't want to tell you what happened. I want to tell you how it felt. When I was twelve, my little brother drowned. He was seven. I was with him. I swam him to shore. His arms were wrapped around my neck from behind, his chest on my back, his knees pummeling my thighs. At first, his small heavy head was on my shoulder, and he breathed in my ear, the occasional snort when water came in. His head bounced. My shoulder ached. His hands were knotted at my collarbone and I held them there with my hand, both so that he wouldn't let go and so that he wouldn't choke me. With my other hand, I pushed the water away.

We had gone to the beach for the day, just the two of us, alone together. This was allowed. This was our whole summer. Our family lived in Baltimore, or in the suburbs really, a place called Pikesville. When June came and set us free from school, and set my father free from his job teaching chemical engineering at Catonsville Community College-my mother was a painter, so she was always free-we would drive three hours down to Delaware, to a town near Bethany Beach, where every year we rented the same narrow gray house with a skew porch out front.

Every morning, after breakfast and cartoons, my brother and I would leave our father to edit his articles and our mother to dab at her paintings. Wayne and I would change into our still-damp swimsuits and I would pack us Capri Suns and Lunchables from the fridge. We would walk along the roads, cutting through a gap between the fancier houses to reach the beach. My mother had told us that the gap was called No Man's Land, which Wayne misheard and took to mean it belonged to a man named Norman. We'd sneak quietly through Norman's Land, then tromp over the boardwalk, our flipflops knocking against it, and find our favorite spot on the shore, which was marked by clumps of sea grass.

Wayne was a nutty brown, a scrawny creature, a good kid. He played so hard, as if play were work. I was too old to play, so I watched him play, and helped sometimes. That day, I buried him for fun's sake. We dug a shallow trench with cupped hands, like dogs, like gardeners. The topsand was cane sugar, the undersand brown sugar. When the trench was big enough, he tumbled into it and I packed the sand onto his body, patpatting it over his hands and over his bony knees. Under the fluorescent sun, he lay still as a magician's assistant.

He asked me to cover his head with our straw hat and I said, "No, you'll suffocate!" He flinched, as if to grab for it himself, then remembered that his hand was buried. Too late: the mound of sand over it had sprouted a crack. He glanced at it, at me. I patpatted the sand back flat. After a moment he said it again, he mouthed, Cover. My. Head. I touched my ...

≈≈≈

I don't want to tell you what happened. I want to tell you how it felt. When I was twelve, my little brother drowned. He was seven. I was with him. I swam him to shore. His arms were wrapped around my neck from behind, his chest on my back, his knees pummeling my thighs. At first, his small heavy head was on my shoulder, and he breathed in my ear, the occasional snort when water came in. His head bounced. My shoulder ached. His hands were knotted at my collarbone and I held them there with my hand, both so that he wouldn't let go and so that he wouldn't choke me. With my other hand, I pushed the water away.

We had gone to the beach for the day, just the two of us, alone together. This was allowed. This was our whole summer. Our family lived in Baltimore, or in the suburbs really, a place called Pikesville. When June came and set us free from school, and set my father free from his job teaching chemical engineering at Catonsville Community College-my mother was a painter, so she was always free-we would drive three hours down to Delaware, to a town near Bethany Beach, where every year we rented the same narrow gray house with a skew porch out front.

Every morning, after breakfast and cartoons, my brother and I would leave our father to edit his articles and our mother to dab at her paintings. Wayne and I would change into our still-damp swimsuits and I would pack us Capri Suns and Lunchables from the fridge. We would walk along the roads, cutting through a gap between the fancier houses to reach the beach. My mother had told us that the gap was called No Man's Land, which Wayne misheard and took to mean it belonged to a man named Norman. We'd sneak quietly through Norman's Land, then tromp over the boardwalk, our flipflops knocking against it, and find our favorite spot on the shore, which was marked by clumps of sea grass.

Wayne was a nutty brown, a scrawny creature, a good kid. He played so hard, as if play were work. I was too old to play, so I watched him play, and helped sometimes. That day, I buried him for fun's sake. We dug a shallow trench with cupped hands, like dogs, like gardeners. The topsand was cane sugar, the undersand brown sugar. When the trench was big enough, he tumbled into it and I packed the sand onto his body, patpatting it over his hands and over his bony knees. Under the fluorescent sun, he lay still as a magician's assistant.

He asked me to cover his head with our straw hat and I said, "No, you'll suffocate!" He flinched, as if to grab for it himself, then remembered that his hand was buried. Too late: the mound of sand over it had sprouted a crack. He glanced at it, at me. I patpatted the sand back flat. After a moment he said it again, he mouthed, Cover. My. Head. I touched my ...

Short Excerpt Teaser

1

≈≈≈

I don't want to tell you what happened. I want to tell you how it felt. When I was twelve, my little brother drowned. He was seven. I was with him. I swam him to shore. His arms were wrapped around my neck from behind, his chest on my back, his knees pummeling my thighs. At first, his small heavy head was on my shoulder, and he breathed in my ear, the occasional snort when water came in. His head bounced. My shoulder ached. His hands were knotted at my collarbone and I held them there with my hand, both so that he wouldn't let go and so that he wouldn't choke me. With my other hand, I pushed the water away.

We had gone to the beach for the day, just the two of us, alone together. This was allowed. This was our whole summer. Our family lived in Baltimore, or in the suburbs really, a place called Pikesville. When June came and set us free from school, and set my father free from his job teaching chemical engineering at Catonsville Community College-my mother was a painter, so she was always free-we would drive three hours down to Delaware, to a town near Bethany Beach, where every year we rented the same narrow gray house with a skew porch out front.

Every morning, after breakfast and cartoons, my brother and I would leave our father to edit his articles and our mother to dab at her paintings. Wayne and I would change into our still-damp swimsuits and I would pack us Capri Suns and Lunchables from the fridge. We would walk along the roads, cutting through a gap between the fancier houses to reach the beach. My mother had told us that the gap was called No Man's Land, which Wayne misheard and took to mean it belonged to a man named Norman. We'd sneak quietly through Norman's Land, then tromp over the boardwalk, our flipflops knocking against it, and find our favorite spot on the shore, which was marked by clumps of sea grass.

Wayne was a nutty brown, a scrawny creature, a good kid. He played so hard, as if play were work. I was too old to play, so I watched him play, and helped sometimes. That day, I buried him for fun's sake. We dug a shallow trench with cupped hands, like dogs, like gardeners. The topsand was cane sugar, the undersand brown sugar. When the trench was big enough, he tumbled into it and I packed the sand onto his body, patpatting it over his hands and over his bony knees. Under the fluorescent sun, he lay still as a magician's assistant.

He asked me to cover his head with our straw hat and I said, "No, you'll suffocate!" He flinched, as if to grab for it himself, then remembered that his hand was buried. Too late: the mound of sand over it had sprouted a crack. He glanced at it, at me. I patpatted the sand back flat. After a moment he said it again, he mouthed, Cover. My. Head. I touched my sandy finger to his sandy cheek. "Close your eyes, Wayne," I said, and placed the straw hat over his squinching face.

I had stolen that hat from a fruit vendor before Wayne was born, when he was still in the womb. Our mother, pregnant and craving, was buying a pear at a stand at a farmers' market. The hat was rolling at the fruit vendor's feet like tumbleweed. It beckoned me and so I picked it up and put it behind my back, switching it quickly to my front when we turned to leave. My mother didn't notice until a block later. She twisted my earlobe till it stung and hissed, "It's too late to give it back now, you little twit!"

Although our family had owned the straw hat for many years now, it was still too big for either of us kids to wear. We used it for carrying things instead, its leather chinstrap serving as a handle. We had used it today to bring lunch and a towel. Now it swallowed his head completely.

"You're a dead Mexican," I giggled.

"Olé!" he muffled from under the hat.

"I mean cowboy," I said.

"Ahoy!"

"That's a sailor."

There was a pause. "Yeehaw!" he said.

I didn't answer. I didn't laugh. I walked away from his buried body, staggered off into the sand pockets toward the greenish sea, bored but deeply satisfied that he would be surprised to find me gone when he lifted that dumb hat off his face. My turn to trick him for once.

My toes were already wet by the time he realized I was gone. He leapt up and tossed the hat and gangled his way toward me. Yelling pellmell, splummeshing past me into the water. I watched his bronze back vanish, then retreated and sat beside the empty trench with my arms around my knees. There was no one else around. It was bright and hot, the end of summer. Then the clouds came and lowered. The wind rose. The waves rose.

≈

Dear Wayne. You swam into the furrows. At first, you didn't know it because you were under the surface and you faced down as you sw...

≈≈≈

I don't want to tell you what happened. I want to tell you how it felt. When I was twelve, my little brother drowned. He was seven. I was with him. I swam him to shore. His arms were wrapped around my neck from behind, his chest on my back, his knees pummeling my thighs. At first, his small heavy head was on my shoulder, and he breathed in my ear, the occasional snort when water came in. His head bounced. My shoulder ached. His hands were knotted at my collarbone and I held them there with my hand, both so that he wouldn't let go and so that he wouldn't choke me. With my other hand, I pushed the water away.

We had gone to the beach for the day, just the two of us, alone together. This was allowed. This was our whole summer. Our family lived in Baltimore, or in the suburbs really, a place called Pikesville. When June came and set us free from school, and set my father free from his job teaching chemical engineering at Catonsville Community College-my mother was a painter, so she was always free-we would drive three hours down to Delaware, to a town near Bethany Beach, where every year we rented the same narrow gray house with a skew porch out front.

Every morning, after breakfast and cartoons, my brother and I would leave our father to edit his articles and our mother to dab at her paintings. Wayne and I would change into our still-damp swimsuits and I would pack us Capri Suns and Lunchables from the fridge. We would walk along the roads, cutting through a gap between the fancier houses to reach the beach. My mother had told us that the gap was called No Man's Land, which Wayne misheard and took to mean it belonged to a man named Norman. We'd sneak quietly through Norman's Land, then tromp over the boardwalk, our flipflops knocking against it, and find our favorite spot on the shore, which was marked by clumps of sea grass.

Wayne was a nutty brown, a scrawny creature, a good kid. He played so hard, as if play were work. I was too old to play, so I watched him play, and helped sometimes. That day, I buried him for fun's sake. We dug a shallow trench with cupped hands, like dogs, like gardeners. The topsand was cane sugar, the undersand brown sugar. When the trench was big enough, he tumbled into it and I packed the sand onto his body, patpatting it over his hands and over his bony knees. Under the fluorescent sun, he lay still as a magician's assistant.

He asked me to cover his head with our straw hat and I said, "No, you'll suffocate!" He flinched, as if to grab for it himself, then remembered that his hand was buried. Too late: the mound of sand over it had sprouted a crack. He glanced at it, at me. I patpatted the sand back flat. After a moment he said it again, he mouthed, Cover. My. Head. I touched my sandy finger to his sandy cheek. "Close your eyes, Wayne," I said, and placed the straw hat over his squinching face.

I had stolen that hat from a fruit vendor before Wayne was born, when he was still in the womb. Our mother, pregnant and craving, was buying a pear at a stand at a farmers' market. The hat was rolling at the fruit vendor's feet like tumbleweed. It beckoned me and so I picked it up and put it behind my back, switching it quickly to my front when we turned to leave. My mother didn't notice until a block later. She twisted my earlobe till it stung and hissed, "It's too late to give it back now, you little twit!"

Although our family had owned the straw hat for many years now, it was still too big for either of us kids to wear. We used it for carrying things instead, its leather chinstrap serving as a handle. We had used it today to bring lunch and a towel. Now it swallowed his head completely.

"You're a dead Mexican," I giggled.

"Olé!" he muffled from under the hat.

"I mean cowboy," I said.

"Ahoy!"

"That's a sailor."

There was a pause. "Yeehaw!" he said.

I didn't answer. I didn't laugh. I walked away from his buried body, staggered off into the sand pockets toward the greenish sea, bored but deeply satisfied that he would be surprised to find me gone when he lifted that dumb hat off his face. My turn to trick him for once.

My toes were already wet by the time he realized I was gone. He leapt up and tossed the hat and gangled his way toward me. Yelling pellmell, splummeshing past me into the water. I watched his bronze back vanish, then retreated and sat beside the empty trench with my arms around my knees. There was no one else around. It was bright and hot, the end of summer. Then the clouds came and lowered. The wind rose. The waves rose.

≈

Dear Wayne. You swam into the furrows. At first, you didn't know it because you were under the surface and you faced down as you sw...