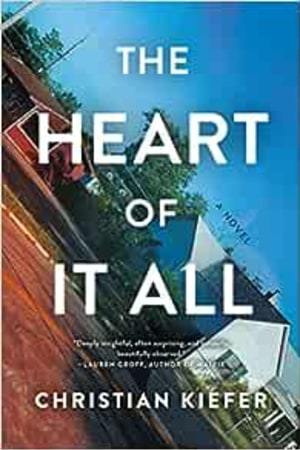

Genre Fiction

- Publisher : Melville House

- Published : 12 Sep 2023

- Pages : 368

- ISBN-10 : 1685890814

- ISBN-13 : 9781685890810

- Language : English

The Heart of It All

"For anyone who believes, as I do, that the best hope for our fractured country is local, not national, Christian Kiefer's new novel The Heart of it All will provide a welcome balm for the spirit. Here are people worth spending time with, not because they're perfect, but because they're not. What's wrong with them isn't nearly as consequential as how hard they fight for a better life, and not just for themselves. You set the book down and think, ‘This is what we're made of.' Or should be."-Richard Russo, author of Somebody's Fool

A small, declining town in Ohio. A family bereaved by terrible loss. A searing narrative about how American lives touch each other across divides both real and imagined...

Set in failing small town in central Ohio, The Heart of It All asks how one manages, in an America of increasing division, to find a sense of family and community.

Focusing on the members of three families: the Baileys, a white family who have put down deep roots in the community; the Marwats, an immigrant family that owns the town's largest employer; and the Shaws, especially young Anthony, an outsider whose very presence gently shakes the town's understanding of itself.

A gorgeous, stirring novel in the classic vein of Richard Ford, Marilynne Robinson, Richard Russo, and Kent Haruf, The Heart of It All asks the reader to consider an America both divided and bound by its differences.

Editorial Reviews

Tom Bailey

Death brought casseroles and Tom took them, every one, his hands numb upon the square glass containers, many warm from the oven, others cold so that their foiled tops wept with moisture. There was nothing to be done but stand and nod and thank people for coming and answer questions about Sarah, yes, she was doing OK, considering, just tired, you know, and nodding again and nodding again and nodding again. He did not even know some of their names, people from church he had seen for years but had never really spoken to. They would tell him how sorry they were, how the Lord works in mysterious ways, how we should all have faith in times of trouble, and if there's anything I can do to help don't hesitate to call, their faces screwed into masks of concern and grief that he knew was real and yet knew also was not their grief to bear but only a mirror of his own. And Sarah's. At least you got to know him for a time before God took him away. At least there was that much. But in the deep well of his heart he wished the baby had died during the pregnancy and that they had not seen him at all, that the six months of his short life were simply erased from his memory and from his wife's memory and from the memories of his two living children. That he had to make such a distinction, to call two of his children living, made him feel a stranger to himself but then he knew that this was who he was now, that this too had been added to the scales.

His mother-in-law bustling by with the latest casserole. Pastor Mitchell in his black clerical garb, head cocked like an intently listening dog before the nearly identical shapes of Tom's neighbors, the Finns. Guests lingering, unsure of how long to stay, but surely wanting to leave, to flee. Did he not want the same? Across the small living room, Sam's head tilted toward the two other members of the bowling team, Betty and Cheryl, the three of them likely engaged in pointless strategizing. Tom desired nothing more than to tell them to grab their gear and meet him at the Bowl-O-Rama; he wanted to watch the machine rack the pins, then that moment of serenity, imperturbable and noiseless, his body simultaneously taught and loose. All there: the release, the skid, that hanging moment just before the frozen ball began to rotate upon its axis, its reflection in the waxed lane, the way it held the gutter's edge before spinning homeward. My God it was perfect. But he was not at the bowling alley. He was in his own living room on a November day in the hours after his infant son's funeral and what kind of man thought of bowling in such a moment? Sam nodded and Betty and Cheryl both opened their mouths in apparent astonishment. And sweet baby James was still in his tiny coffin under the turned soil of the cemetery. This was what was.

Death brought casseroles and Tom took them, every one, his hands numb upon the square glass containers, many warm from the oven, others cold so that their foiled tops wept with moisture. There was nothing to be done but stand and nod and thank people for coming and answer questions about Sarah, yes, she was doing OK, considering, just tired, you know, and nodding again and nodding again and nodding again. He did not even know some of their names, people from church he had seen for years but had never really spoken to. They would tell him how sorry they were, how the Lord works in mysterious ways, how we should all have faith in times of trouble, and if there's anything I can do to help don't hesitate to call, their faces screwed into masks of concern and grief that he knew was real and yet knew also was not their grief to bear but only a mirror of his own. And Sarah's. At least you got to know him for a time before God took him away. At least there was that much. But in the deep well of his heart he wished the baby had died during the pregnancy and that they had not seen him at all, that the six months of his short life were simply erased from his memory and from his wife's memory and from the memories of his two living children. That he had to make such a distinction, to call two of his children living, made him feel a stranger to himself but then he knew that this was who he was now, that this too had been added to the scales.

His mother-in-law bustling by with the latest casserole. Pastor Mitchell in his black clerical garb, head cocked like an intently listening dog before the nearly identical shapes of Tom's neighbors, the Finns. Guests lingering, unsure of how long to stay, but surely wanting to leave, to flee. Did he not want the same? Across the small living room, Sam's head tilted toward the two other members of the bowling team, Betty and Cheryl, the three of them likely engaged in pointless strategizing. Tom desired nothing more than to tell them to grab their gear and meet him at the Bowl-O-Rama; he wanted to watch the machine rack the pins, then that moment of serenity, imperturbable and noiseless, his body simultaneously taught and loose. All there: the release, the skid, that hanging moment just before the frozen ball began to rotate upon its axis, its reflection in the waxed lane, the way it held the gutter's edge before spinning homeward. My God it was perfect. But he was not at the bowling alley. He was in his own living room on a November day in the hours after his infant son's funeral and what kind of man thought of bowling in such a moment? Sam nodded and Betty and Cheryl both opened their mouths in apparent astonishment. And sweet baby James was still in his tiny coffin under the turned soil of the cemetery. This was what was.

Short Excerpt Teaser

Tom Bailey

Death brought casseroles and Tom took them, every one, his hands numb upon the square glass containers, many warm from the oven, others cold so that their foiled tops wept with moisture. There was nothing to be done but stand and nod and thank people for coming and answer questions about Sarah, yes, she was doing OK, considering, just tired, you know, and nodding again and nodding again and nodding again. He did not even know some of their names, people from church he had seen for years but had never really spoken to. They would tell him how sorry they were, how the Lord works in mysterious ways, how we should all have faith in times of trouble, and if there's anything I can do to help don't hesitate to call, their faces screwed into masks of concern and grief that he knew was real and yet knew also was not their grief to bear but only a mirror of his own. And Sarah's. At least you got to know him for a time before God took him away. At least there was that much. But in the deep well of his heart he wished the baby had died during the pregnancy and that they had not seen him at all, that the six months of his short life were simply erased from his memory and from his wife's memory and from the memories of his two living children. That he had to make such a distinction, to call two of his children living, made him feel a stranger to himself but then he knew that this was who he was now, that this too had been added to the scales.

His mother-in-law bustling by with the latest casserole. Pastor Mitchell in his black clerical garb, head cocked like an intently listening dog before the nearly identical shapes of Tom's neighbors, the Finns. Guests lingering, unsure of how long to stay, but surely wanting to leave, to flee. Did he not want the same? Across the small living room, Sam's head tilted toward the two other members of the bowling team, Betty and Cheryl, the three of them likely engaged in pointless strategizing. Tom desired nothing more than to tell them to grab their gear and meet him at the Bowl-O-Rama; he wanted to watch the machine rack the pins, then that moment of serenity, imperturbable and noiseless, his body simultaneously taught and loose. All there: the release, the skid, that hanging moment just before the frozen ball began to rotate upon its axis, its reflection in the waxed lane, the way it held the gutter's edge before spinning homeward. My God it was perfect. But he was not at the bowling alley. He was in his own living room on a November day in the hours after his infant son's funeral and what kind of man thought of bowling in such a moment? Sam nodded and Betty and Cheryl both opened their mouths in apparent astonishment. And sweet baby James was still in his tiny coffin under the turned soil of the cemetery. This was what was.

Sam's wife, Amy, was before him now, her hair recently recolored so that the slanting light from the window lit its outline in shades of maroon. "You tell her to call me," she said. "Whatever you need. And I know people say that all the time but really, Tom, whatever you need, you just pick up the phone."

"I appreciate that." He nodded for emphasis.

Amy patting his shoulder as if he were a pet of some kind. "Oh, honey, I can't imagine what you're all going through," and when he said nothing in response, for what could he say, she said: "Well, you just call us if you need anything. Really, Tom. Friends and family. We're both, aren't we?"

"Sure, Amy," he said.

"And make sure Sarah knows that too. I went back there to the bedroom, you know, just to see her, but she's sleeping now and thank God for that. I mean, God knows she needs her rest. So you make sure she knows I'm here for her."

"I'm sure she already knows that, Amy."

"I know she does but tell her anyway."

He told her he would. He knew she meant well, that she was-despite what Sam sometimes said about her-a good person, or was trying to be a good person, was trying, that is, in the way we all try and fail to be what we are not, to be better than who we actually are.

From somewhere toward the kitchen: his mother-in-law's voice. She had driven down from Wisconsin a week before, had set up the funeral arrangements, and had insisted on this reception, or whatever it was. He did not know what he wanted except that it was not this but Sarah had said nothing, nothing at all, and so, in the end, he had acquiesced, meeting her silence with his own, his mother-in-law's bustling energy both welcome and unwelcome, achieving things that he simply did not have the heart to do himself. Yes there was to be a funeral. For a baby. For his baby. James. How strange to think of such a thing. The coffin had been so small. Like a toy. Sarah like crushed paper. Her moth...

Death brought casseroles and Tom took them, every one, his hands numb upon the square glass containers, many warm from the oven, others cold so that their foiled tops wept with moisture. There was nothing to be done but stand and nod and thank people for coming and answer questions about Sarah, yes, she was doing OK, considering, just tired, you know, and nodding again and nodding again and nodding again. He did not even know some of their names, people from church he had seen for years but had never really spoken to. They would tell him how sorry they were, how the Lord works in mysterious ways, how we should all have faith in times of trouble, and if there's anything I can do to help don't hesitate to call, their faces screwed into masks of concern and grief that he knew was real and yet knew also was not their grief to bear but only a mirror of his own. And Sarah's. At least you got to know him for a time before God took him away. At least there was that much. But in the deep well of his heart he wished the baby had died during the pregnancy and that they had not seen him at all, that the six months of his short life were simply erased from his memory and from his wife's memory and from the memories of his two living children. That he had to make such a distinction, to call two of his children living, made him feel a stranger to himself but then he knew that this was who he was now, that this too had been added to the scales.

His mother-in-law bustling by with the latest casserole. Pastor Mitchell in his black clerical garb, head cocked like an intently listening dog before the nearly identical shapes of Tom's neighbors, the Finns. Guests lingering, unsure of how long to stay, but surely wanting to leave, to flee. Did he not want the same? Across the small living room, Sam's head tilted toward the two other members of the bowling team, Betty and Cheryl, the three of them likely engaged in pointless strategizing. Tom desired nothing more than to tell them to grab their gear and meet him at the Bowl-O-Rama; he wanted to watch the machine rack the pins, then that moment of serenity, imperturbable and noiseless, his body simultaneously taught and loose. All there: the release, the skid, that hanging moment just before the frozen ball began to rotate upon its axis, its reflection in the waxed lane, the way it held the gutter's edge before spinning homeward. My God it was perfect. But he was not at the bowling alley. He was in his own living room on a November day in the hours after his infant son's funeral and what kind of man thought of bowling in such a moment? Sam nodded and Betty and Cheryl both opened their mouths in apparent astonishment. And sweet baby James was still in his tiny coffin under the turned soil of the cemetery. This was what was.

Sam's wife, Amy, was before him now, her hair recently recolored so that the slanting light from the window lit its outline in shades of maroon. "You tell her to call me," she said. "Whatever you need. And I know people say that all the time but really, Tom, whatever you need, you just pick up the phone."

"I appreciate that." He nodded for emphasis.

Amy patting his shoulder as if he were a pet of some kind. "Oh, honey, I can't imagine what you're all going through," and when he said nothing in response, for what could he say, she said: "Well, you just call us if you need anything. Really, Tom. Friends and family. We're both, aren't we?"

"Sure, Amy," he said.

"And make sure Sarah knows that too. I went back there to the bedroom, you know, just to see her, but she's sleeping now and thank God for that. I mean, God knows she needs her rest. So you make sure she knows I'm here for her."

"I'm sure she already knows that, Amy."

"I know she does but tell her anyway."

He told her he would. He knew she meant well, that she was-despite what Sam sometimes said about her-a good person, or was trying to be a good person, was trying, that is, in the way we all try and fail to be what we are not, to be better than who we actually are.

From somewhere toward the kitchen: his mother-in-law's voice. She had driven down from Wisconsin a week before, had set up the funeral arrangements, and had insisted on this reception, or whatever it was. He did not know what he wanted except that it was not this but Sarah had said nothing, nothing at all, and so, in the end, he had acquiesced, meeting her silence with his own, his mother-in-law's bustling energy both welcome and unwelcome, achieving things that he simply did not have the heart to do himself. Yes there was to be a funeral. For a baby. For his baby. James. How strange to think of such a thing. The coffin had been so small. Like a toy. Sarah like crushed paper. Her moth...