Americas

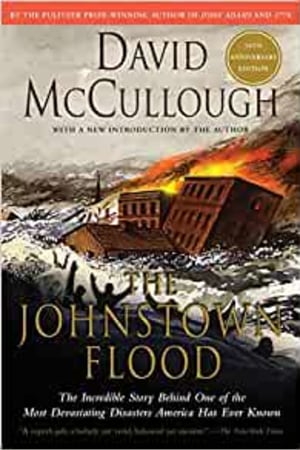

- Publisher : Simon & Schuster; Reprint edition

- Published : 15 Jan 1987

- Pages : 304

- ISBN-10 : 0671207148

- ISBN-13 : 9780671207144

- Language : English

The Johnstown Flood

The stunning story of one of America's great disasters, a preventable tragedy of Gilded Age America, brilliantly told by master historian David McCullough.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Johnstown, Pennsylvania, was a booming coal-and-steel town filled with hardworking families striving for a piece of the nation's burgeoning industrial prosperity. In the mountains above Johnstown, an old earth dam had been hastily rebuilt to create a lake for an exclusive summer resort patronized by the tycoons of that same industrial prosperity, among them Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and Andrew Mellon. Despite repeated warnings of possible danger, nothing was done about the dam. Then came May 31, 1889, when the dam burst, sending a wall of water thundering down the mountain, smashing through Johnstown, and killing more than 2,000 people. It was a tragedy that became a national scandal.

Graced by David McCullough's remarkable gift for writing richly textured, sympathetic social history, The Johnstown Flood is an absorbing, classic portrait of life in nineteenth-century America, of overweening confidence, of energy, and of tragedy. It also offers a powerful historical lesson for our century and all times: the danger of assuming that because people are in positions of responsibility they are necessarily behaving responsibly.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Johnstown, Pennsylvania, was a booming coal-and-steel town filled with hardworking families striving for a piece of the nation's burgeoning industrial prosperity. In the mountains above Johnstown, an old earth dam had been hastily rebuilt to create a lake for an exclusive summer resort patronized by the tycoons of that same industrial prosperity, among them Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and Andrew Mellon. Despite repeated warnings of possible danger, nothing was done about the dam. Then came May 31, 1889, when the dam burst, sending a wall of water thundering down the mountain, smashing through Johnstown, and killing more than 2,000 people. It was a tragedy that became a national scandal.

Graced by David McCullough's remarkable gift for writing richly textured, sympathetic social history, The Johnstown Flood is an absorbing, classic portrait of life in nineteenth-century America, of overweening confidence, of energy, and of tragedy. It also offers a powerful historical lesson for our century and all times: the danger of assuming that because people are in positions of responsibility they are necessarily behaving responsibly.

Editorial Reviews

The New Yorker A first rate example of the documentary method....Mr. McCullough is a good writer and painstaking reporter and he has re-created that now almost mythic cataclysm...with the thoroughness the subject demands.

Book World McCullough has resurrected the flood for a generation that may know it in name only. He proves the subject is still fresh and spectacular.

John Leonard The New York Times We have no better social historian.

Book World McCullough has resurrected the flood for a generation that may know it in name only. He proves the subject is still fresh and spectacular.

John Leonard The New York Times We have no better social historian.

Readers Top Reviews

Doug JayR HelenKi

Probably the least known disaster that has occurred in the USA, the Johnstown flood of 1889 resulted in over 2000 deaths, massive financial loss and the devastation of a thriving Pennsylvania community. Johnstown was located at the bottom of a river valley which made it susceptible to serious but manageable flooding during periods of sustained and heavy rainfall. In 1852, an earth dam was constructed some 15 miles upstream of Johnstown in order to create a lake which would serve to provide top-up water for a canal system which unfortunately was obsolete by the time the dam was completed. Over the next thirty years, the dam and surrounding lands changed ownership several times, maintenance was carried out on an ad hoc basis and the lake was always substantially below the capacity of the dam to retain the waters. However, in 1879 a group of extremely wealthy business men purchased the area and began building an exclusive fishing and hunting facility which would eventually see the lake increase to its full capacity thereby putting the ill-maintained dam under maximum stress. Very little effort was made to establish the strength and underlying condition of the dam and the inhabitants of downstream communities regularly expressed concern that under conditions of heavy rainfall the dam would break with catastrophic results. Such an eventuality was realised in May 1889 when after a prolonged period of storms and heavy rainfall, the dam overtopped and progressively collapsed sending millions of tons of water hurtling down the valley towards Johnstown and intermediate smaller communities. David McCullough in this, his first book, describes in excellent detail the background and consequences of the ensuing inundation that became known as the Johnstown flood as it was that township that suffered the greatest loss of life and property. Any readers already familiar with the author’s later books will not be disappointed with this first publication as it exhibits a profound level of research resulting in a very readable and informative narrative. Well worth reading even if you are not interested in modern American history.

DavidDoug JayR He

This aspect of culpability, in fact, a lack of culpability, is quite striking throughout David McCullough's well-written and researched narrative. The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, founded in 1879 by Benjamin Ruff, was a private, elitist and highly secretive summer resort for Pittsburgh's leading industrialists and financier's such as Henry Clay Frick, Andrew Carnegie, Andrew Mellon and the like, together with other less well-known personages, albeit still wealthy and influential, with a limited number of other members who were well connected. The club owned the South Fork lake, dam, clubhouse, cottages and some 160 acres of surrounding land. The lake and dam were located at an elevation of 1618 feet (493 metres) above Johnstown on the slopes of the Allegheny Mountain range, a distance of some 15 miles from Johnstown. In 1879, Benjamin Ruff purchased the lake and dam plus other property detailed above and created an exclusive club. A number of significant modifications were made to the dam under Ruff's ownership, most of which were instrumental in its collapse - but you need to read the book to appreciate these. The lake just prior to the dam collapsing was approximately 2 miles in length (3.2 km) and nearly a mile (1.6 km) at its widest point and had a water level of circa 72 feet (22 metres). The dam itself was 931 feet in width (284 metres) made from an earth core with rubble facing. On the 31 May 1889 the dam was holding back some 20 million tons (18,144 metric tonne) of water. Heavy rainfall had swollen the lake such that water was pouring over the top centre section of the dam, gradually eroding the earth until suddenly the dam gave way released the lake water, creating a wall of water travelling at 420,000 cubic feet per second (12,000 cubic metres per second) heading straight for Jamestown. Witnesses said the entire lake emptied in 57 to 65 minutes (estimates vary somewhat), the wall of water some 40 feet (12 metres) in height nearest the ground with the top layer cascading over the lower layer, which was subject to more ground drag resistance, reaching an estimated height of perhaps 100 feet (30.5 metres approximately). The devastation to property, possessions and the loss of life (many of those killed were never found) was catastrophic. But here's the strange part: no one was held accountable. Culpability didn't come into any of the subsequent reports or litigation cases, all of which failed. Why? Well, by the time of the dam collapsed, Benjamin Ruff was dead. The argument being put forward by senior club members was that Ruff was responsible for repairs to the dam and those wealthy members of the club placed their confidence in Ruff's professional experience and knowledge, when in fact, Ruff was not professionally qualified in any shape or form and some of his so-called repairs were nothing short of an amateur bodge, that prove...

hmusgroveDavidDou

For some reason, this David McCullough book wasn't on my radar. Having read many of his others, with my favorite being The Path Between the Seas, I was excited see a McCullough I hadn't read. Then lo and behold, this was the one that began his career! Having never heard of this tragedy, I was immediately intrigued and of course was not disappointed once I dove in, no pun intended. The Johnstown Flood is a detailed tribute and accounting of the victims' life and times, and a timeless story of classism and its consequences. And at 300 pages, it's an excellent, non-intimidating introduction to McCullough's style and level of detail. Highly recommend!

AncientDiscoveryh

This is the book that launched McCullough's career as one of our foremost chroniclers of history. It's a tragic story, and over a century later, is still one of the worst disasters in U.S. history. McCullough gives a voice to those distant victims and survivors (some were still alive when he wrote this book). To read their story makes the Johnstown Flood not seem so distant. That's what good narrative history does: Connects us to our past and brings it forward to the present. We can still learn from the Flood: The neglect of the dam (and the people) by the elite; the hardworking citizens trying to scratch out a living in a country booming full-speed ahead; and how in all that death and destruction, the people rebuilt and moved forward. Even now, the terror is hard to imagine, but equally hard to forget: Many of the dead, never identified some never found. And, sadly, no one was held responsible for all these lives lost.

Joseph SciutoAnci

David McCullough is one of my favorite historians, and along with another dozen historians over the last forty years, they have literally corrected the "history" of the United States and the world and have made almost everything I learned back in school during the seventies and eighties absolute. "The Johnstown Flood" is the first major book published by Mr. McCullough fifty years ago. It is the last of two books by this great author that I had not read... Mainly because the subject matter of which I knew very little about did not seem to interest me like his other books. Naturally, my assumption was wrong and the subject of the great flood that literally destroyed the entire town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania and killed at least two thousand citizens very quickly became a subject of great interest to me. An old earth dam, miles above the town, that was hastily rebuilt to create a lake for fishing and sailing for an exclusive summer resort that catered to industrial tycoons like Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick. Warnings about the safety of the dam had been circulating around the area and the nearby towns for years, but very little was done about it. They simply became rumors, until May 31, 1889, when torrential rains savaged the area and the dam broke and the destruction was a catastrophe, uplifting buildings and homes and hundred year old trees like paper machetes and smashing them to pieces... Along with the remains of thousands of people. The tragedy made headlines throughout the country and there was an outpouring of help from people and organizations from all parts of the country and the world. It was at the time of the industrial revolution in the United States, and as Mr. McCullough carefully details the dam, the clientele belonging to the resort, and the destruction of the natural barriers that would have prevented such a tragedy were all part of the revolution that would transform the United States and the world. It is a chilling reminder of the power of nature and man's disregard of such power and the deadly consequences of such neglect. I highly recommend.

Short Excerpt Teaser

Chapter 1

The sky was red

Again that morning there had been a bright frost in the hollow below the dam, and the sun was not up long before storm clouds rolled in from the southeast.

By late afternoon a sharp, gusty wind was blowing down from the mountains, flattening the long grass along the lakeshore and kicking up tiny whitecaps out in the center of the lake. The big oaks and giant hemlocks, the hickories and black birch and sugar maples that crowded the hillside behind the summer colony began tossing back and forth, creaking and groaning. Broken branches and young leaves whipped through the air, and at the immense frame clubhouse that stood at the water's edge, halfway among the cottages, blue wood smoke trailed from great brick chimneys and vanished in fast swirls, almost as though the whole building, like a splendid yellow ark, were under steam, heading into the wind.

The colony was known as the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. It was a private summer resort located on the western shore of a mountain lake in Cambria County, Pennsylvania, about halfway between the crest of the Allegheny range and the city of Johnstown. On the afternoon of Thursday, May 30, Memorial Day, 1889, the club was not quite ten years old, but with its gaily painted buildings, its neat lawns and well-tended flower beds, it looked spanking new and, in the gray, stormy half-light, slightly out of season.

In three weeks, when the summer season was to start, something like 200 guests were expected. Now the place looked practically deserted. The only people about were a few employees who lived at the clubhouse and some half dozen members who had come up from Pittsburgh for the holiday. D. W. C. Bidwell was there; so were the young Clarke brothers, J. J. Lawrence, and several of the Sheas and Irwins. Every now and then a cottage door slammed, voices called back and forth from the boathouses. Then there would be silence again, except for the sound of the wind.

Sometime not long after dark, it may have been about eight thirty, a young man stepped out onto the long front porch at the clubhouse and walked to the railing to take a look at the weather. His name was John G. Parke, Jr. He was clean-shaven, slight of build, and rather aristocratic-looking. He was the nephew and namesake of General John G. Parke, then superintendent of West Point. But young Parke was a rare item in his own right for that part of the country; he was a college man, having finished three years of civil engineering at the University of Pennsylvania. For the present he was employed by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club as the so-called "resident engineer." He had been on the job just short of three months, seeing to general repairs, looking after the dam, and supervising a crew of some twenty Italian laborers who had been hired to install a new indoor plumbing system, and who were now camped out of sight, back in the woods.

In the pitch dark he could hardly see a thing, so he stepped down the porch stairs and went a short distance along the boardwalk that led through the trees to the cottages. The walk, he noticed, was slightly damp. Apparently, a fine rain had fallen sometime while he was inside having his supper. He also noticed that though the wind was still up, the sky overhead was not so dark as before; indeed, it seemed to be clearing off some. This was not what he had expected. Windstorms on the mountain nearly always meant a heavy downpour almost immediately after -- "thunder-gusts" the local men called them. Parke had been through several already in the time he had been at the lake and knew what to expect.

par

It would be as though the whole sky were laying siege to the burly landscape. The rain would drum down like an unyielding river. Lightning would flash blue-white, again and again across the sky, and thunderclaps would boom back and forth down the valley like a cannonade, rattling every window along the lakeshore.

Then, almost as suddenly as it had started, the siege would lift, and silent, milky steam would rise from the surface of the water and the rank smell of the sodden forest floor would hang on in the air for hours.

Tonight, however, it appeared there was to be no storm. Parke turned and walked back inside. About nine-thirty he went upstairs, climbed into bed, and went to deep.

About an hour and a half later, very near eleven, the rain began. It came damming through the blackness in huge wind-driven sheets, beating against the clubhouse, the tossing trees, the lake, and the dark, untamed country that stretched off in every direction for miles and miles.

The storm had started out of Kansas and Nebraska, two days be...

The sky was red

Again that morning there had been a bright frost in the hollow below the dam, and the sun was not up long before storm clouds rolled in from the southeast.

By late afternoon a sharp, gusty wind was blowing down from the mountains, flattening the long grass along the lakeshore and kicking up tiny whitecaps out in the center of the lake. The big oaks and giant hemlocks, the hickories and black birch and sugar maples that crowded the hillside behind the summer colony began tossing back and forth, creaking and groaning. Broken branches and young leaves whipped through the air, and at the immense frame clubhouse that stood at the water's edge, halfway among the cottages, blue wood smoke trailed from great brick chimneys and vanished in fast swirls, almost as though the whole building, like a splendid yellow ark, were under steam, heading into the wind.

The colony was known as the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. It was a private summer resort located on the western shore of a mountain lake in Cambria County, Pennsylvania, about halfway between the crest of the Allegheny range and the city of Johnstown. On the afternoon of Thursday, May 30, Memorial Day, 1889, the club was not quite ten years old, but with its gaily painted buildings, its neat lawns and well-tended flower beds, it looked spanking new and, in the gray, stormy half-light, slightly out of season.

In three weeks, when the summer season was to start, something like 200 guests were expected. Now the place looked practically deserted. The only people about were a few employees who lived at the clubhouse and some half dozen members who had come up from Pittsburgh for the holiday. D. W. C. Bidwell was there; so were the young Clarke brothers, J. J. Lawrence, and several of the Sheas and Irwins. Every now and then a cottage door slammed, voices called back and forth from the boathouses. Then there would be silence again, except for the sound of the wind.

Sometime not long after dark, it may have been about eight thirty, a young man stepped out onto the long front porch at the clubhouse and walked to the railing to take a look at the weather. His name was John G. Parke, Jr. He was clean-shaven, slight of build, and rather aristocratic-looking. He was the nephew and namesake of General John G. Parke, then superintendent of West Point. But young Parke was a rare item in his own right for that part of the country; he was a college man, having finished three years of civil engineering at the University of Pennsylvania. For the present he was employed by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club as the so-called "resident engineer." He had been on the job just short of three months, seeing to general repairs, looking after the dam, and supervising a crew of some twenty Italian laborers who had been hired to install a new indoor plumbing system, and who were now camped out of sight, back in the woods.

In the pitch dark he could hardly see a thing, so he stepped down the porch stairs and went a short distance along the boardwalk that led through the trees to the cottages. The walk, he noticed, was slightly damp. Apparently, a fine rain had fallen sometime while he was inside having his supper. He also noticed that though the wind was still up, the sky overhead was not so dark as before; indeed, it seemed to be clearing off some. This was not what he had expected. Windstorms on the mountain nearly always meant a heavy downpour almost immediately after -- "thunder-gusts" the local men called them. Parke had been through several already in the time he had been at the lake and knew what to expect.

par

It would be as though the whole sky were laying siege to the burly landscape. The rain would drum down like an unyielding river. Lightning would flash blue-white, again and again across the sky, and thunderclaps would boom back and forth down the valley like a cannonade, rattling every window along the lakeshore.

Then, almost as suddenly as it had started, the siege would lift, and silent, milky steam would rise from the surface of the water and the rank smell of the sodden forest floor would hang on in the air for hours.

Tonight, however, it appeared there was to be no storm. Parke turned and walked back inside. About nine-thirty he went upstairs, climbed into bed, and went to deep.

About an hour and a half later, very near eleven, the rain began. It came damming through the blackness in huge wind-driven sheets, beating against the clubhouse, the tossing trees, the lake, and the dark, untamed country that stretched off in every direction for miles and miles.

The storm had started out of Kansas and Nebraska, two days be...