Literature & Fiction

- Publisher : Anchor; Reprint edition

- Published : 09 Nov 2021

- Pages : 288

- ISBN-10 : 0593311868

- ISBN-13 : 9780593311868

- Language : English

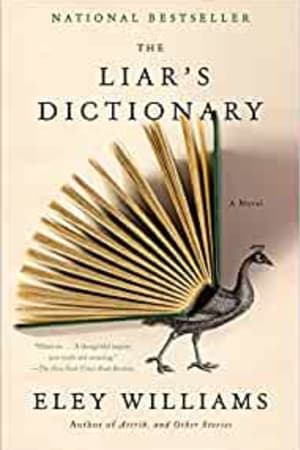

The Liar's Dictionary: A Novel

NATIONAL BESTSELLER • "You wouldn't expect a comic novel about a dictionary to be a thriller too, but this one is. In fact, [it] is also a mystery, love story (two of them) and cliffhanging melodrama." -The New York Times Book Review

An award-winning novel that chronicles the charming misadventures of a lovelorn Victorian lexicographer and the young woman put on his trail a century later to root out his misdeeds while confronting questions of her own sexuality and place in the world.

Mountweazel n. the phenomenon of false entries within dictionaries and works of reference. Often used as a safeguard against copyright infringement.

In the final year of the nineteenth century, Peter Winceworth is toiling away at the letter S for Swansby's multivolume Encyclopaedic Dictionary. But his disaffection with his colleagues compels him to assert some individual purpose and artistic freedom, and he begins inserting unauthorized, fictitious entries. In the present day, Mallory, the publisher's young intern, starts to uncover these mountweazels in the process of digitization and through them senses their creator's motivations, hopes, and desires. More pressingly, she's also been contending with a threatening, anonymous caller who wants Swansby's staff to "burn in hell." As these two narratives coalesce, Winceworth and Mallory, separated by one hundred years, must discover how to negotiate the complexities of life's often untrustworthy, hoax-strewn, and undefinable path. An exhilarating, laugh-out-loud debut, The Liar's Dictionary celebrates the rigidity, fragility, absurdity, and joy of language while peering into questions of identity and finding one's place in the world.

An award-winning novel that chronicles the charming misadventures of a lovelorn Victorian lexicographer and the young woman put on his trail a century later to root out his misdeeds while confronting questions of her own sexuality and place in the world.

Mountweazel n. the phenomenon of false entries within dictionaries and works of reference. Often used as a safeguard against copyright infringement.

In the final year of the nineteenth century, Peter Winceworth is toiling away at the letter S for Swansby's multivolume Encyclopaedic Dictionary. But his disaffection with his colleagues compels him to assert some individual purpose and artistic freedom, and he begins inserting unauthorized, fictitious entries. In the present day, Mallory, the publisher's young intern, starts to uncover these mountweazels in the process of digitization and through them senses their creator's motivations, hopes, and desires. More pressingly, she's also been contending with a threatening, anonymous caller who wants Swansby's staff to "burn in hell." As these two narratives coalesce, Winceworth and Mallory, separated by one hundred years, must discover how to negotiate the complexities of life's often untrustworthy, hoax-strewn, and undefinable path. An exhilarating, laugh-out-loud debut, The Liar's Dictionary celebrates the rigidity, fragility, absurdity, and joy of language while peering into questions of identity and finding one's place in the world.

Editorial Reviews

A is for artful (adj.)

David spoke at me for three minutes without realising I had a whole egg in my mouth.

I had adopted my usual stance to eat my lunch-hunched over in the stationa/ery cupboard between the printer cartridges and stacked columns of parcel tape. Noon. It can be a fine thing to snuffle your lunch and often the highlight of a working day. Many's the time I've stood in Swansby House's cupboard beneath its skylight lapping soup straight from the carton or chase-licking individual grains of leftover rice from a stained piece of Tupperware. This kind of lunch will taste all the better when eaten unobserved.

I popped a hard-boiled egg into my mouth and chewed, reading a dozen words for envelope printed in different languages down the side of some supply boxes. To pass the time I tried memorising each term. Boríték remains the only Hungarian I know apart from Biró and Rubik, named after their inventors-the penman and the human puzzle. I chose a second hard-boiled egg and put it in my mouth.

There was the usual degree of snaffling, face-in-trough rootling when the door opened and editor-in-chief David Swansby sidestepped into the cupboard.

It was only etiquette that gave David this title, really. He came from a great line of Swansby editors-in-chief. I was his only employee.

I stared, egg-bound, as he slipped through the door and pressed it shut behind him.

"Ah, Mallory," David said. "Glad I've caught you. Might I have a word?"

He was a handsome seventy-year-old with a spry demonstrative way of using his hands which was not suited to such a small cupboard. I've heard people say that dog owners often look like their pets, or the pets look like their owners. In many ways David Swansby looked like his handwriting: ludicrously tall, neat, squared off at the edges. Like my handwriting, I was aware that I often looked as though I needed to be tidied away, or ironed, possibly autoclaved. By the time afternoon tugged itself around the clock, both handwriting and I degrade into a big rumpled bundle. I'm being coy in my choice of words: rumpled, like shabby and well-worn, places emphasis on cosiness and affability-I mean that I looked like a mess by the end of the day. Creases seemed to find me and made tally charts against my clothes and my skin as I counted down the hours until home time. This didn't matter too much at Swansby House.

David Swansby was not a physically threatening presence and it would be unfair to say I was cornered by him in the cupboard. The room was not big enough for two people, however, and a corner was involved and certainly in that moment I was directly relevant to that noun becoming a verb.

I waited for my boss to tell me what he needed, but he insisted on small talk. He mentioned something mil...

David spoke at me for three minutes without realising I had a whole egg in my mouth.

I had adopted my usual stance to eat my lunch-hunched over in the stationa/ery cupboard between the printer cartridges and stacked columns of parcel tape. Noon. It can be a fine thing to snuffle your lunch and often the highlight of a working day. Many's the time I've stood in Swansby House's cupboard beneath its skylight lapping soup straight from the carton or chase-licking individual grains of leftover rice from a stained piece of Tupperware. This kind of lunch will taste all the better when eaten unobserved.

I popped a hard-boiled egg into my mouth and chewed, reading a dozen words for envelope printed in different languages down the side of some supply boxes. To pass the time I tried memorising each term. Boríték remains the only Hungarian I know apart from Biró and Rubik, named after their inventors-the penman and the human puzzle. I chose a second hard-boiled egg and put it in my mouth.

There was the usual degree of snaffling, face-in-trough rootling when the door opened and editor-in-chief David Swansby sidestepped into the cupboard.

It was only etiquette that gave David this title, really. He came from a great line of Swansby editors-in-chief. I was his only employee.

I stared, egg-bound, as he slipped through the door and pressed it shut behind him.

"Ah, Mallory," David said. "Glad I've caught you. Might I have a word?"

He was a handsome seventy-year-old with a spry demonstrative way of using his hands which was not suited to such a small cupboard. I've heard people say that dog owners often look like their pets, or the pets look like their owners. In many ways David Swansby looked like his handwriting: ludicrously tall, neat, squared off at the edges. Like my handwriting, I was aware that I often looked as though I needed to be tidied away, or ironed, possibly autoclaved. By the time afternoon tugged itself around the clock, both handwriting and I degrade into a big rumpled bundle. I'm being coy in my choice of words: rumpled, like shabby and well-worn, places emphasis on cosiness and affability-I mean that I looked like a mess by the end of the day. Creases seemed to find me and made tally charts against my clothes and my skin as I counted down the hours until home time. This didn't matter too much at Swansby House.

David Swansby was not a physically threatening presence and it would be unfair to say I was cornered by him in the cupboard. The room was not big enough for two people, however, and a corner was involved and certainly in that moment I was directly relevant to that noun becoming a verb.

I waited for my boss to tell me what he needed, but he insisted on small talk. He mentioned something mil...

Readers Top Reviews

Zannie

This is a book for word nerds. Fortunately I am one. I must admit I was worried it would be a bit too clever for my normal reading and when it arrived I didn’t know if the dust jacket was on upside down as a mistake by the publishers or it was some kind of convoluted initiative test. That aside, I read it slowly and joyously, rereading favourite phrases and cringing in empathy with the awkwardness of the two protagonists whose social gaffs were only too redolent of my own as an intern and in my early career. Although the plot is more pedestrian than the wickedly precise prose, it is not lacking for interest and several of the characters stayed with me far beyond my finishing of the book. A debut novel too marvellous for words. Williams’ short story collection Attrib. is also worth reading.

M. Ross

A unique and captivating writer who deserves to have a very long shelf life. Thoroughly enjoyable book for a lazy weekend with poor weather, devoured in three sittings leaving me very satisfied and wanting more, much more.

M. JefferiesR. A. Co

There is considerable hype surrounding this novel and puff after puff from distinguished writers and critics. I really wanted to like it and the premise seemed intriguing, literary and entertaining. However, the writing, for me, is painfully clunky and downright dull. The characters are mere caricatures, the plot non-existent and the pacing is all over the place. There are excruciatingly bad scenes where the pursuit of wit and inventiveness proves fruitless. The Frosham party scene is a good example. The writing here is so bad it grates like fingernails on a blackboard. Unfortunately, the wordplay that assumes the starring role of intelligent prose-making in the novel is laboured and obvious and makes for clunky intrusions rather than the intended delightful artistry. Hysterically overhyped in my opinion. Pick up an Iris Murdoch instead. There are loads of them. Witty, intelligent and entertaining.

aleigh_powersEsperan

The wordplay in this novel is absolutely decadent - delicious even, and I ate up every bit of it. But, if you're looking for story, don't look here. So much of absolutely nothing happens. Or, it begins to FINALLY happen, and the novel ends. The protagonists make absolutely no progress, there is no growth or character arc of note. Mallory does make a small step. At the very end. And that's about it. The characters are full & flat, written in big flourishes like a signature that takes up all of the line for no reason because you can't make it out. There is a wonderful scene in a restaurant between two characters and I thought, "Here we go, here is the start!" The wonderful banter and back and forth is so well written that I can envision the scene in full color and sound and found myself fully engrossed in the conversation being had. And then it's over, and we're back to humdrum characters and a plot that ends and doesn't at the same time. I give this two stars: for the wonderful and witty writing. But I can't give any more for a story that was just ... almost.

Short Excerpt Teaser

A is for artful (adj.)

David spoke at me for three minutes without realising I had a whole egg in my mouth.

I had adopted my usual stance to eat my lunch-hunched over in the stationa/ery cupboard between the printer cartridges and stacked columns of parcel tape. Noon. It can be a fine thing to snuffle your lunch and often the highlight of a working day. Many's the time I've stood in Swansby House's cupboard beneath its skylight lapping soup straight from the carton or chase-licking individual grains of leftover rice from a stained piece of Tupperware. This kind of lunch will taste all the better when eaten unobserved.

I popped a hard-boiled egg into my mouth and chewed, reading a dozen words for envelope printed in different languages down the side of some supply boxes. To pass the time I tried memorising each term. Boríték remains the only Hungarian I know apart from Biró and Rubik, named after their inventors-the penman and the human puzzle. I chose a second hard-boiled egg and put it in my mouth.

There was the usual degree of snaffling, face-in-trough rootling when the door opened and editor-in-chief David Swansby sidestepped into the cupboard.

It was only etiquette that gave David this title, really. He came from a great line of Swansby editors-in-chief. I was his only employee.

I stared, egg-bound, as he slipped through the door and pressed it shut behind him.

"Ah, Mallory," David said. "Glad I've caught you. Might I have a word?"

He was a handsome seventy-year-old with a spry demonstrative way of using his hands which was not suited to such a small cupboard. I've heard people say that dog owners often look like their pets, or the pets look like their owners. In many ways David Swansby looked like his handwriting: ludicrously tall, neat, squared off at the edges. Like my handwriting, I was aware that I often looked as though I needed to be tidied away, or ironed, possibly autoclaved. By the time afternoon tugged itself around the clock, both handwriting and I degrade into a big rumpled bundle. I'm being coy in my choice of words: rumpled, like shabby and well-worn, places emphasis on cosiness and affability-I mean that I looked like a mess by the end of the day. Creases seemed to find me and made tally charts against my clothes and my skin as I counted down the hours until home time. This didn't matter too much at Swansby House.

David Swansby was not a physically threatening presence and it would be unfair to say I was cornered by him in the cupboard. The room was not big enough for two people, however, and a corner was involved and certainly in that moment I was directly relevant to that noun becoming a verb.

I waited for my boss to tell me what he needed, but he insisted on small talk. He mentioned something mild about the weather and recent sporting triumphs and dismays, then mentioned the weather again, and when he had got that out of the way I began to panic, mouth eggfulsome: surely now he must be expecting me to offer some response or to vouchsafe or confess or at the very least contribute a thought of my own? I considered what would happen if I tried to swallow the egg whole or chew it and speak around it, act as if this was normal behaviour. Or should I calmly spit it, gleaming and tooth-notched, into my hand and ask David to spit out what it was he wanted, as if it was the most casual thing in the world?

David twiddled the handle of a label dispenser on a shelf near his eye. He straightened it a touch. This is editorial behaviour, I thought. He glanced up at the skylight.

"I can't get over this light," he said. "Can you? So clear."

I mumbled.

"Just look at that." He switched his gaze from the skylight to his shoes in their weak pool of sunlight.

For my part, appreciative noises.

"Apricide," David said. He pronounced it with fervour. People who work with words like to do this: enunciate with admiring flourishes as if a connoisseur and to show that here was someone who knew the value of a good word, the terroir of its etymology and the rarity of its vintage. Then he frowned, paused. He did not correct himself, but unfortunately I remembered this word from Vol. I of Swansby's New Encyclopaedic Dictionary. David meant apricity (n.), the warmness of the sun in winter. Apricide (n.) means the ceremonial slaughter of pigs.

You might spot a volume of Swansby's New Encyclopaedic Dictionary mouldering somewhere as a prop book on a gastropub mantelpiece or occasionally see one being passed from church fete bookstall to charity shop to hamster-bedding manufacturer in your local area. Not the first nor the best and certainly not the most famous dictionary of the English language, Swansby's has always been a poor shadow of its com...

David spoke at me for three minutes without realising I had a whole egg in my mouth.

I had adopted my usual stance to eat my lunch-hunched over in the stationa/ery cupboard between the printer cartridges and stacked columns of parcel tape. Noon. It can be a fine thing to snuffle your lunch and often the highlight of a working day. Many's the time I've stood in Swansby House's cupboard beneath its skylight lapping soup straight from the carton or chase-licking individual grains of leftover rice from a stained piece of Tupperware. This kind of lunch will taste all the better when eaten unobserved.

I popped a hard-boiled egg into my mouth and chewed, reading a dozen words for envelope printed in different languages down the side of some supply boxes. To pass the time I tried memorising each term. Boríték remains the only Hungarian I know apart from Biró and Rubik, named after their inventors-the penman and the human puzzle. I chose a second hard-boiled egg and put it in my mouth.

There was the usual degree of snaffling, face-in-trough rootling when the door opened and editor-in-chief David Swansby sidestepped into the cupboard.

It was only etiquette that gave David this title, really. He came from a great line of Swansby editors-in-chief. I was his only employee.

I stared, egg-bound, as he slipped through the door and pressed it shut behind him.

"Ah, Mallory," David said. "Glad I've caught you. Might I have a word?"

He was a handsome seventy-year-old with a spry demonstrative way of using his hands which was not suited to such a small cupboard. I've heard people say that dog owners often look like their pets, or the pets look like their owners. In many ways David Swansby looked like his handwriting: ludicrously tall, neat, squared off at the edges. Like my handwriting, I was aware that I often looked as though I needed to be tidied away, or ironed, possibly autoclaved. By the time afternoon tugged itself around the clock, both handwriting and I degrade into a big rumpled bundle. I'm being coy in my choice of words: rumpled, like shabby and well-worn, places emphasis on cosiness and affability-I mean that I looked like a mess by the end of the day. Creases seemed to find me and made tally charts against my clothes and my skin as I counted down the hours until home time. This didn't matter too much at Swansby House.

David Swansby was not a physically threatening presence and it would be unfair to say I was cornered by him in the cupboard. The room was not big enough for two people, however, and a corner was involved and certainly in that moment I was directly relevant to that noun becoming a verb.

I waited for my boss to tell me what he needed, but he insisted on small talk. He mentioned something mild about the weather and recent sporting triumphs and dismays, then mentioned the weather again, and when he had got that out of the way I began to panic, mouth eggfulsome: surely now he must be expecting me to offer some response or to vouchsafe or confess or at the very least contribute a thought of my own? I considered what would happen if I tried to swallow the egg whole or chew it and speak around it, act as if this was normal behaviour. Or should I calmly spit it, gleaming and tooth-notched, into my hand and ask David to spit out what it was he wanted, as if it was the most casual thing in the world?

David twiddled the handle of a label dispenser on a shelf near his eye. He straightened it a touch. This is editorial behaviour, I thought. He glanced up at the skylight.

"I can't get over this light," he said. "Can you? So clear."

I mumbled.

"Just look at that." He switched his gaze from the skylight to his shoes in their weak pool of sunlight.

For my part, appreciative noises.

"Apricide," David said. He pronounced it with fervour. People who work with words like to do this: enunciate with admiring flourishes as if a connoisseur and to show that here was someone who knew the value of a good word, the terroir of its etymology and the rarity of its vintage. Then he frowned, paused. He did not correct himself, but unfortunately I remembered this word from Vol. I of Swansby's New Encyclopaedic Dictionary. David meant apricity (n.), the warmness of the sun in winter. Apricide (n.) means the ceremonial slaughter of pigs.

You might spot a volume of Swansby's New Encyclopaedic Dictionary mouldering somewhere as a prop book on a gastropub mantelpiece or occasionally see one being passed from church fete bookstall to charity shop to hamster-bedding manufacturer in your local area. Not the first nor the best and certainly not the most famous dictionary of the English language, Swansby's has always been a poor shadow of its com...