Literature & Fiction

- Publisher : Scribner

- Published : 03 Jan 2023

- Pages : 400

- ISBN-10 : 1668000830

- ISBN-13 : 9781668000830

- Language : English

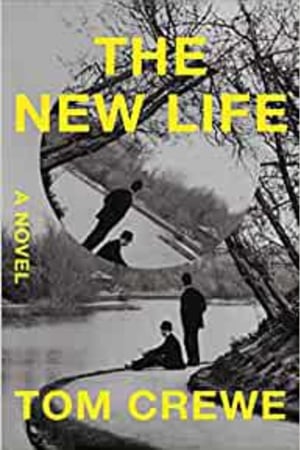

The New Life: A Novel

A brilliant and captivating debut, in the tradition of Alan Hollinghurst and Colm Tóibín, about two marriages, two forbidden love affairs, and the passionate search for social and sexual freedom in late 19th-century London.

In this powerful, visceral novel about love, sex, and the struggle for a better world, two men collaborate on a book in defense of homosexuality, then a crime-risking their old lives in the process.

In the summer of 1894, John Addington and Henry Ellis begin writing a book arguing that what they call "inversion," or homosexuality, is a natural, harmless variation of human sexuality. Though they have never met, John and Henry both live in London with their wives, Catherine and Edith, and in each marriage there is a third party: John has a lover, a working class man named Frank, and Edith spends almost as much time with her friend Angelica as she does with Henry. John and Catherine have three grown daughters and a long, settled marriage, over the course of which Catherine has tried to accept her husband's sexuality and her own role in life; Henry and Edith's marriage is intended to be a revolution in itself, an intellectual partnership that dismantles the traditional understanding of what matrimony means.

Shortly before the book is to be published, Oscar Wilde is arrested. John and Henry must decide whether to go on, risking social ostracism and imprisonment, or to give up the project for their own safety and the safety of the people they love. Is this the right moment to advance their cause? Is publishing bravery or foolishness? And what price is too high to pay for a new way of living?

A richly detailed, insightful, and dramatic debut novel, The New Life is an unforgettable portrait of two men, a city, and a generation discovering the nature and limits of personal freedom as the 20th century comes into view.

In this powerful, visceral novel about love, sex, and the struggle for a better world, two men collaborate on a book in defense of homosexuality, then a crime-risking their old lives in the process.

In the summer of 1894, John Addington and Henry Ellis begin writing a book arguing that what they call "inversion," or homosexuality, is a natural, harmless variation of human sexuality. Though they have never met, John and Henry both live in London with their wives, Catherine and Edith, and in each marriage there is a third party: John has a lover, a working class man named Frank, and Edith spends almost as much time with her friend Angelica as she does with Henry. John and Catherine have three grown daughters and a long, settled marriage, over the course of which Catherine has tried to accept her husband's sexuality and her own role in life; Henry and Edith's marriage is intended to be a revolution in itself, an intellectual partnership that dismantles the traditional understanding of what matrimony means.

Shortly before the book is to be published, Oscar Wilde is arrested. John and Henry must decide whether to go on, risking social ostracism and imprisonment, or to give up the project for their own safety and the safety of the people they love. Is this the right moment to advance their cause? Is publishing bravery or foolishness? And what price is too high to pay for a new way of living?

A richly detailed, insightful, and dramatic debut novel, The New Life is an unforgettable portrait of two men, a city, and a generation discovering the nature and limits of personal freedom as the 20th century comes into view.

Editorial Reviews

Chapter I I

HE WAS CLOSE ENOUGH to smell the hairs on the back of the man's neck. They almost tickled him, and he tried to rear his head, but found that he was wedged too tightly. There were too many bodies pressed heavily around him; he was slotted into a pattern of hats, shoulders, elbows, knees, feet. He could not move his head even an inch. His gaze had been slotted too, broken off at the edges: he could see nothing but the back of this man's head, the white margin of his collar, the span of his shoulders. He was close enough to smell the pomade, streaks of it shining dully at the man's nape; clingings of eau de cologne, a tang of salt. The suit the man was wearing was blue-and-gray check. The white collar bit slightly into his skin, fringed by small whitish hairs. His ears were pink where they curved at the top. His hat-John could see barely higher than the brim-was dark brown, with a band in a lighter shade. His hair was brown too, darker where the pomade was daubed. It had recently been cut: a line traced where the barber had shaped it.

John could not move his head. His arms were trapped at his sides; there were bodies pressing from right and left, from behind, in front. He flexed his fingers-they brushed coats, dresses, satchels, canes, umbrellas. The train carriage rattled in its frame, thudded on the track, underground. The lights wavered, trembling on the cheekbone of the man in front. John hadn't noticed that, hadn't noticed he could see the angle of the man's jaw and the jut of his cheekbone. There was the hint of a moustache. Blackness rushed past the windows. The floor roared beneath his feet.

He was hard. The man had changed position, or John had. Perhaps it was only a jolt of the train. But someone had changed their position. The man's jacket scratched at John's stomach-he felt it as an itch-and his buttocks brushed against John's crotch, once, twice, another time. John was hard. It was far too hot in the train, far too crowded. The man came closer, still just within the realm of accident, his buttocks now pressed against John's crotch. John's erection was cramped flat against his body. The man and he were so close it was cocooned between them. Surely he could feel it? A high, vanishing feeling traveled up from John's groin, tingling in his fingertips and at his temples. He could not get away, could not turn his head, could only smell the hairs on the back of the man's neck, see the neat line of his collar, the redness on the tops of his ears, could only feel himself hard, harder than before, as though his body were concentrating itself, straining in that one spot. Surely he could feel it? John felt panicked; sweat collected in his armpits. He dreaded the man succeeding in pivoting about, skewering the other passengers with his elbows...

HE WAS CLOSE ENOUGH to smell the hairs on the back of the man's neck. They almost tickled him, and he tried to rear his head, but found that he was wedged too tightly. There were too many bodies pressed heavily around him; he was slotted into a pattern of hats, shoulders, elbows, knees, feet. He could not move his head even an inch. His gaze had been slotted too, broken off at the edges: he could see nothing but the back of this man's head, the white margin of his collar, the span of his shoulders. He was close enough to smell the pomade, streaks of it shining dully at the man's nape; clingings of eau de cologne, a tang of salt. The suit the man was wearing was blue-and-gray check. The white collar bit slightly into his skin, fringed by small whitish hairs. His ears were pink where they curved at the top. His hat-John could see barely higher than the brim-was dark brown, with a band in a lighter shade. His hair was brown too, darker where the pomade was daubed. It had recently been cut: a line traced where the barber had shaped it.

John could not move his head. His arms were trapped at his sides; there were bodies pressing from right and left, from behind, in front. He flexed his fingers-they brushed coats, dresses, satchels, canes, umbrellas. The train carriage rattled in its frame, thudded on the track, underground. The lights wavered, trembling on the cheekbone of the man in front. John hadn't noticed that, hadn't noticed he could see the angle of the man's jaw and the jut of his cheekbone. There was the hint of a moustache. Blackness rushed past the windows. The floor roared beneath his feet.

He was hard. The man had changed position, or John had. Perhaps it was only a jolt of the train. But someone had changed their position. The man's jacket scratched at John's stomach-he felt it as an itch-and his buttocks brushed against John's crotch, once, twice, another time. John was hard. It was far too hot in the train, far too crowded. The man came closer, still just within the realm of accident, his buttocks now pressed against John's crotch. John's erection was cramped flat against his body. The man and he were so close it was cocooned between them. Surely he could feel it? A high, vanishing feeling traveled up from John's groin, tingling in his fingertips and at his temples. He could not get away, could not turn his head, could only smell the hairs on the back of the man's neck, see the neat line of his collar, the redness on the tops of his ears, could only feel himself hard, harder than before, as though his body were concentrating itself, straining in that one spot. Surely he could feel it? John felt panicked; sweat collected in his armpits. He dreaded the man succeeding in pivoting about, skewering the other passengers with his elbows...

Short Excerpt Teaser

Chapter I I

HE WAS CLOSE ENOUGH to smell the hairs on the back of the man's neck. They almost tickled him, and he tried to rear his head, but found that he was wedged too tightly. There were too many bodies pressed heavily around him; he was slotted into a pattern of hats, shoulders, elbows, knees, feet. He could not move his head even an inch. His gaze had been slotted too, broken off at the edges: he could see nothing but the back of this man's head, the white margin of his collar, the span of his shoulders. He was close enough to smell the pomade, streaks of it shining dully at the man's nape; clingings of eau de cologne, a tang of salt. The suit the man was wearing was blue-and-gray check. The white collar bit slightly into his skin, fringed by small whitish hairs. His ears were pink where they curved at the top. His hat-John could see barely higher than the brim-was dark brown, with a band in a lighter shade. His hair was brown too, darker where the pomade was daubed. It had recently been cut: a line traced where the barber had shaped it.

John could not move his head. His arms were trapped at his sides; there were bodies pressing from right and left, from behind, in front. He flexed his fingers-they brushed coats, dresses, satchels, canes, umbrellas. The train carriage rattled in its frame, thudded on the track, underground. The lights wavered, trembling on the cheekbone of the man in front. John hadn't noticed that, hadn't noticed he could see the angle of the man's jaw and the jut of his cheekbone. There was the hint of a moustache. Blackness rushed past the windows. The floor roared beneath his feet.

He was hard. The man had changed position, or John had. Perhaps it was only a jolt of the train. But someone had changed their position. The man's jacket scratched at John's stomach-he felt it as an itch-and his buttocks brushed against John's crotch, once, twice, another time. John was hard. It was far too hot in the train, far too crowded. The man came closer, still just within the realm of accident, his buttocks now pressed against John's crotch. John's erection was cramped flat against his body. The man and he were so close it was cocooned between them. Surely he could feel it? A high, vanishing feeling traveled up from John's groin, tingling in his fingertips and at his temples. He could not get away, could not turn his head, could only smell the hairs on the back of the man's neck, see the neat line of his collar, the redness on the tops of his ears, could only feel himself hard, harder than before, as though his body were concentrating itself, straining in that one spot. Surely he could feel it? John felt panicked; sweat collected in his armpits. He dreaded the man succeeding in pivoting about, skewering the other passengers with his elbows, shouting something, the carriage turning its eyes, a gap opening round his telltale shame. And yet he knew that he did not want it to stop, that he could not escape the grip of this terrible excitement.

The man began to move. At first John was not certain, he thought again that it might be the jolting of the train. He had been willing the hardness away, counting from a hundred in his head, breathing slowly through his teeth, when he felt the slightest movement, as though the man were pushing back against his erection, as though he were gently tilting against it, rising and falling on his toes. John's first sensation was a rush of dread, followed quickly by a rush of something else, that same high, vanishing feeling running through his fingers and up to his temples. He had no control. He was crowded on all sides-he was fixed at the center of a mass of bodies, his entire consciousness constricted, committed to this small circle of subtle movement. This man's buttocks, pressed so tightly against him it almost hurt, moving up and down. A bead of sweat, released from his armpit, ran quickly and coldly down his side. He tried to look about him, at the other passengers, but could not: instead he gazed frantically, surrenderingly, at the man's collar, the redness on his ears. Was that a smile, creeping to the edge of the moustache? And still it went on, unmistakable now, the rising and falling, the pressure, almost painful, moving up the length of him, to the tip and down again. He breathed heavily through his nose, breathed heavily onto the man's neck. He wished he could move his arms, that he could move anything at all: that his whole being were not bent so terrifyingly on this sensation, this experience, that he could for a moment place himself outside it. He breathed heavily again, saw how his breath flattened the whitish hairs on the back of the man's neck. His face hurt. He felt a strange pressure under his ears. He swallowed, took another breath. Pomade and...

HE WAS CLOSE ENOUGH to smell the hairs on the back of the man's neck. They almost tickled him, and he tried to rear his head, but found that he was wedged too tightly. There were too many bodies pressed heavily around him; he was slotted into a pattern of hats, shoulders, elbows, knees, feet. He could not move his head even an inch. His gaze had been slotted too, broken off at the edges: he could see nothing but the back of this man's head, the white margin of his collar, the span of his shoulders. He was close enough to smell the pomade, streaks of it shining dully at the man's nape; clingings of eau de cologne, a tang of salt. The suit the man was wearing was blue-and-gray check. The white collar bit slightly into his skin, fringed by small whitish hairs. His ears were pink where they curved at the top. His hat-John could see barely higher than the brim-was dark brown, with a band in a lighter shade. His hair was brown too, darker where the pomade was daubed. It had recently been cut: a line traced where the barber had shaped it.

John could not move his head. His arms were trapped at his sides; there were bodies pressing from right and left, from behind, in front. He flexed his fingers-they brushed coats, dresses, satchels, canes, umbrellas. The train carriage rattled in its frame, thudded on the track, underground. The lights wavered, trembling on the cheekbone of the man in front. John hadn't noticed that, hadn't noticed he could see the angle of the man's jaw and the jut of his cheekbone. There was the hint of a moustache. Blackness rushed past the windows. The floor roared beneath his feet.

He was hard. The man had changed position, or John had. Perhaps it was only a jolt of the train. But someone had changed their position. The man's jacket scratched at John's stomach-he felt it as an itch-and his buttocks brushed against John's crotch, once, twice, another time. John was hard. It was far too hot in the train, far too crowded. The man came closer, still just within the realm of accident, his buttocks now pressed against John's crotch. John's erection was cramped flat against his body. The man and he were so close it was cocooned between them. Surely he could feel it? A high, vanishing feeling traveled up from John's groin, tingling in his fingertips and at his temples. He could not get away, could not turn his head, could only smell the hairs on the back of the man's neck, see the neat line of his collar, the redness on the tops of his ears, could only feel himself hard, harder than before, as though his body were concentrating itself, straining in that one spot. Surely he could feel it? John felt panicked; sweat collected in his armpits. He dreaded the man succeeding in pivoting about, skewering the other passengers with his elbows, shouting something, the carriage turning its eyes, a gap opening round his telltale shame. And yet he knew that he did not want it to stop, that he could not escape the grip of this terrible excitement.

The man began to move. At first John was not certain, he thought again that it might be the jolting of the train. He had been willing the hardness away, counting from a hundred in his head, breathing slowly through his teeth, when he felt the slightest movement, as though the man were pushing back against his erection, as though he were gently tilting against it, rising and falling on his toes. John's first sensation was a rush of dread, followed quickly by a rush of something else, that same high, vanishing feeling running through his fingers and up to his temples. He had no control. He was crowded on all sides-he was fixed at the center of a mass of bodies, his entire consciousness constricted, committed to this small circle of subtle movement. This man's buttocks, pressed so tightly against him it almost hurt, moving up and down. A bead of sweat, released from his armpit, ran quickly and coldly down his side. He tried to look about him, at the other passengers, but could not: instead he gazed frantically, surrenderingly, at the man's collar, the redness on his ears. Was that a smile, creeping to the edge of the moustache? And still it went on, unmistakable now, the rising and falling, the pressure, almost painful, moving up the length of him, to the tip and down again. He breathed heavily through his nose, breathed heavily onto the man's neck. He wished he could move his arms, that he could move anything at all: that his whole being were not bent so terrifyingly on this sensation, this experience, that he could for a moment place himself outside it. He breathed heavily again, saw how his breath flattened the whitish hairs on the back of the man's neck. His face hurt. He felt a strange pressure under his ears. He swallowed, took another breath. Pomade and...