Literature & Fiction

- Publisher : One World

- Published : 18 Oct 2022

- Pages : 352

- ISBN-10 : 0593133463

- ISBN-13 : 9780593133460

- Language : English

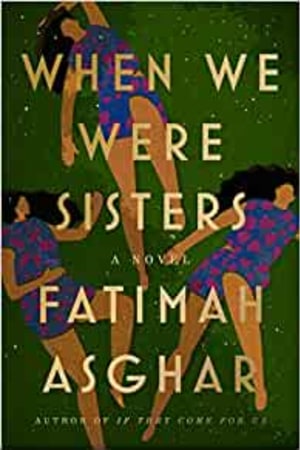

When We Were Sisters: A Novel

LONGLISTED FOR THE NATIONAL BOOK AWARD • An orphan grapples with gender, siblinghood, family, and coming-of-age as a Muslim in America in this lyrical debut novel that "shimmers with love" (Los Angeles Times), from the acclaimed author of If They Come For Us

"Asghar's brilliant coming-of-age story is filled with emotionally raw characters and tender prose."-PopSugar

In this heartrending, lyrical debut work of fiction, Fatimah Asghar traces the intense bond of three orphaned siblings who, after their parents die, are left to raise one another. The youngest, Kausar, grapples with the incomprehensible loss of their parents as she also charts out her own understanding of gender; Aisha, the middle sister, spars with her "crybaby" younger sibling as she desperately tries to hold on to her sense of family in an impossible situation; and Noreen, the eldest, does her best in the role of sister-mother while also trying to create a life for herself, on her own terms.

As Kausar grows up, she must contend with the collision of her private and public worlds, and choose whether to remain in the life of love, sorrow, and codependency that she's known or carve out a new path for herself. When We Were Sisters tenderly examines the bonds and fractures of sisterhood, names the perils of being three Muslim American girls alone against the world, and ultimately illustrates how those who've lost everything might still make homes in one another.

LONGLISTED FOR THE CENTER FOR FICTION FIRST NOVEL PRIZE

"Asghar's brilliant coming-of-age story is filled with emotionally raw characters and tender prose."-PopSugar

In this heartrending, lyrical debut work of fiction, Fatimah Asghar traces the intense bond of three orphaned siblings who, after their parents die, are left to raise one another. The youngest, Kausar, grapples with the incomprehensible loss of their parents as she also charts out her own understanding of gender; Aisha, the middle sister, spars with her "crybaby" younger sibling as she desperately tries to hold on to her sense of family in an impossible situation; and Noreen, the eldest, does her best in the role of sister-mother while also trying to create a life for herself, on her own terms.

As Kausar grows up, she must contend with the collision of her private and public worlds, and choose whether to remain in the life of love, sorrow, and codependency that she's known or carve out a new path for herself. When We Were Sisters tenderly examines the bonds and fractures of sisterhood, names the perils of being three Muslim American girls alone against the world, and ultimately illustrates how those who've lost everything might still make homes in one another.

LONGLISTED FOR THE CENTER FOR FICTION FIRST NOVEL PRIZE

Editorial Reviews

"Pop culture will have us believe that all parentless pain must be channelised into greatness in a Potter world or a Gotham City. Asghar's triumph lies in completely reclaiming identities from any such stereotypical lens. . . . Our complexities are not unidirectional: we have all had experiences where we feel like we've been overlooked. [Fatima] Asghar shows a distinctive aptitude for translating the unsaid in our lives into emotions the characters contend with. Yet, they do it with a lyrical vulnerability that truly captures the world view of the place and the age of their characters."-Vogue India

"Lyrical, heartrending."-Autostraddle

"[A] heartrending and lyrical novel . . . stunning."-She Does the City

"A lyrical Bildungsroman."-The Millions

"When We Were Sisters is a stunning accomplishment in form, storytelling, and heart. This novel works language into its most jeweled form, into characters, sisters, that will stay with me for the rest of my life."-Safia Elhillo, author of Home Is Not a Country and Girls That Never Die

"In this captivating, gorgeously written book, Asghar weaves a tale of sisters in the wake of unspeakable loss. Propulsively readable and experimental in form, this is an unflinching look at family, grief, and reclamation-of self and other."-Hala Alyan, author of Salt Houses and The Arsonists' City

"When We Were Sisters is a beautiful, richly layered exploration of the generosity that is required to raise oneself, to raise others, to build a world where the people you love can feel safe and whole. Fatimah Asghar is an impressive writer precisely because of how she doesn't withhold tenderness, and lets it play and flourish amongst all of the brilliant lyricism, narrative sharpness, and vibrant characters who fill this incredible book."-Hanif Abdurraqib, author of A Little Devil in Americ...

"Lyrical, heartrending."-Autostraddle

"[A] heartrending and lyrical novel . . . stunning."-She Does the City

"A lyrical Bildungsroman."-The Millions

"When We Were Sisters is a stunning accomplishment in form, storytelling, and heart. This novel works language into its most jeweled form, into characters, sisters, that will stay with me for the rest of my life."-Safia Elhillo, author of Home Is Not a Country and Girls That Never Die

"In this captivating, gorgeously written book, Asghar weaves a tale of sisters in the wake of unspeakable loss. Propulsively readable and experimental in form, this is an unflinching look at family, grief, and reclamation-of self and other."-Hala Alyan, author of Salt Houses and The Arsonists' City

"When We Were Sisters is a beautiful, richly layered exploration of the generosity that is required to raise oneself, to raise others, to build a world where the people you love can feel safe and whole. Fatimah Asghar is an impressive writer precisely because of how she doesn't withhold tenderness, and lets it play and flourish amongst all of the brilliant lyricism, narrative sharpness, and vibrant characters who fill this incredible book."-Hanif Abdurraqib, author of A Little Devil in Americ...

Short Excerpt Teaser

Chapter 1

1995

In a city, a man dies and all the Aunties who Aunty the neighborhood reach towards their phones. Their brown fingers cradle porcelain, the news spreading fast and careless as a common cold. Ring! [ ] is dead. Ring! Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji'un. Ring! How sad. Ring! Only a few years after his wife. Ring! And his daughters? Ring! Three of them, yes. Ring! Alive. Ring! Ya Allah. Ring! [ ] is dead.

A man dies in a city he was not born in. Murdered. In the street. (Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji'un.) A man dies in a city he only lived in for a handful of years. (How lonely.) A man dies in a city that his children were born in, but a city that will never be theirs, in a country that will never be theirs, on land that will never be theirs. (Ya Allah.) A father dies and the city and his children keep on living, the lights twinkling from apartment building to apartment building. All around the city, breath flows easily. All around the man, breath slows to a stop. The sky, who sees everything, looks down at him. And the moon, who is full, shines her milky dress on his dead body, bedded by the cement street.

In a city, a man dies. In a suburb of a different state, the man's brother-in-law celebrates by adding an extension to his family's house. A new deck spills out into their backyard. The man's brother-in-law renovates the basement: old moldy carpet pulled up and Moroccan marble tiles put in its place. The brother-in-law pores over them at the Home Depot, comparing prices, how happy it will make his wife, white, who he married when he first came to America. A gorra? his mom asked, the brown women in his family looking at each other, confused. She found Islam because of me! he explained, exacerbated, not understanding why people couldn't see how he was going to earn extra points to heaven, his love enough to make someone convert. You went to America and fell out of love with us, his mom sighed, dramatic, as usual.

But brown women were so plentiful. He knew he could have them. White women found every simple thing he did exciting. It opened him. The lota in the bathroom, a marvel. Basic fruit chaat, the spiciest thing they'd ever tasted. How interesting he could become. A gorra? his cousins in Pakistan echoed in disbelief, some whispering mashallah as others turned away from him. Yes, a gorra. His gorra, her slender nose, all her features pulled towards it, her voice fast like lightning. When they first married, she'd take him around to her American friends. Him: so exotic and fun. They had two sons: brown, but fair. For a while it was good. Or maybe never fully good, but bearable. But when the quiet arrived it stayed. Rooted into his bones. The coldness between them, rattling his chest on every inhale. He still gets to see his sons on weekends, lives in an apartment on his own. Her American friends, their selfishness, filling her head with ideas of a divorce.

I divorce you. I divorce you. I-

All the things he's done to keep her from saying it a third time. Divorce. Ya Allah, what people would think. Divorce. He can't even bring himself to think it a third time in a row. So American it bursts his skin to hives, so American it bows his head when he walks by the Pakistani men at the masjid who mutter about his failed business practices: the roofing scheme he tried to start, the gardening venture, the haraam liquor store. His failure is a reputation that clings to him. That clings to his wife. That clings to his sons. Even when he boasted about the great family he comes from. What they were back in Pakistan. Their name, their honor, what they contributed. People would be polite, they listened and nodded. Then they got tired. They would look away. If only he could make more money. Maybe he could see his sons more. Maybe he could see her more. Maybe she'd walk next to him as he entered the masjid.

When his little sister was alive, when they were kids, she looked at him like he could do no wrong. Her eyes big and full of wonder. Bhai. No one else had ever looked at him like that. She grew up and got married, had kids, made her own life. And then she stopped looking at him that way. When she died he buried the pain deep in his stomach. Tried to convince his sons to love him while their mom called him a useless sack of shit behind his back.

It's not until his sister's husband dies that his stomach begins to bubble. He realizes how much he's missed that look from when they were kids, how she was the only one who believed he could do anything. How much he missed someone believing that about him. How, through her eyes, he believed it too.

It's sad business, his nieces orphaned a few states away. Sad business, their girlness. Sad business th...

1995

In a city, a man dies and all the Aunties who Aunty the neighborhood reach towards their phones. Their brown fingers cradle porcelain, the news spreading fast and careless as a common cold. Ring! [ ] is dead. Ring! Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji'un. Ring! How sad. Ring! Only a few years after his wife. Ring! And his daughters? Ring! Three of them, yes. Ring! Alive. Ring! Ya Allah. Ring! [ ] is dead.

A man dies in a city he was not born in. Murdered. In the street. (Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji'un.) A man dies in a city he only lived in for a handful of years. (How lonely.) A man dies in a city that his children were born in, but a city that will never be theirs, in a country that will never be theirs, on land that will never be theirs. (Ya Allah.) A father dies and the city and his children keep on living, the lights twinkling from apartment building to apartment building. All around the city, breath flows easily. All around the man, breath slows to a stop. The sky, who sees everything, looks down at him. And the moon, who is full, shines her milky dress on his dead body, bedded by the cement street.

In a city, a man dies. In a suburb of a different state, the man's brother-in-law celebrates by adding an extension to his family's house. A new deck spills out into their backyard. The man's brother-in-law renovates the basement: old moldy carpet pulled up and Moroccan marble tiles put in its place. The brother-in-law pores over them at the Home Depot, comparing prices, how happy it will make his wife, white, who he married when he first came to America. A gorra? his mom asked, the brown women in his family looking at each other, confused. She found Islam because of me! he explained, exacerbated, not understanding why people couldn't see how he was going to earn extra points to heaven, his love enough to make someone convert. You went to America and fell out of love with us, his mom sighed, dramatic, as usual.

But brown women were so plentiful. He knew he could have them. White women found every simple thing he did exciting. It opened him. The lota in the bathroom, a marvel. Basic fruit chaat, the spiciest thing they'd ever tasted. How interesting he could become. A gorra? his cousins in Pakistan echoed in disbelief, some whispering mashallah as others turned away from him. Yes, a gorra. His gorra, her slender nose, all her features pulled towards it, her voice fast like lightning. When they first married, she'd take him around to her American friends. Him: so exotic and fun. They had two sons: brown, but fair. For a while it was good. Or maybe never fully good, but bearable. But when the quiet arrived it stayed. Rooted into his bones. The coldness between them, rattling his chest on every inhale. He still gets to see his sons on weekends, lives in an apartment on his own. Her American friends, their selfishness, filling her head with ideas of a divorce.

I divorce you. I divorce you. I-

All the things he's done to keep her from saying it a third time. Divorce. Ya Allah, what people would think. Divorce. He can't even bring himself to think it a third time in a row. So American it bursts his skin to hives, so American it bows his head when he walks by the Pakistani men at the masjid who mutter about his failed business practices: the roofing scheme he tried to start, the gardening venture, the haraam liquor store. His failure is a reputation that clings to him. That clings to his wife. That clings to his sons. Even when he boasted about the great family he comes from. What they were back in Pakistan. Their name, their honor, what they contributed. People would be polite, they listened and nodded. Then they got tired. They would look away. If only he could make more money. Maybe he could see his sons more. Maybe he could see her more. Maybe she'd walk next to him as he entered the masjid.

When his little sister was alive, when they were kids, she looked at him like he could do no wrong. Her eyes big and full of wonder. Bhai. No one else had ever looked at him like that. She grew up and got married, had kids, made her own life. And then she stopped looking at him that way. When she died he buried the pain deep in his stomach. Tried to convince his sons to love him while their mom called him a useless sack of shit behind his back.

It's not until his sister's husband dies that his stomach begins to bubble. He realizes how much he's missed that look from when they were kids, how she was the only one who believed he could do anything. How much he missed someone believing that about him. How, through her eyes, he believed it too.

It's sad business, his nieces orphaned a few states away. Sad business, their girlness. Sad business th...