Genre Fiction

- Publisher : Ballantine Books

- Published : 15 Mar 2022

- Pages : 384

- ISBN-10 : 0593356012

- ISBN-13 : 9780593356012

- Language : English

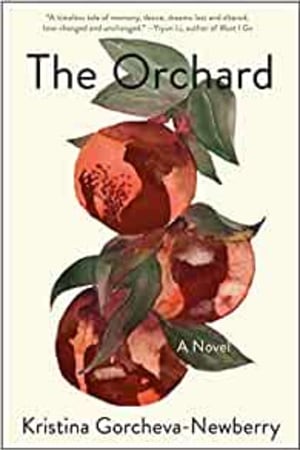

The Orchard: A Novel

Four teenagers grow inseparable in the last days of the Soviet Union-but not all of them will live to see the new world arrive in this powerful debut novel, loosely based on Anton Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard.

"Aching and sexy, clear-eyed and heartbreaking . . . an exquisite, explosive debut."-Julia Phillips, author of Disappearing Earth

Coming of age in the USSR in the 1980s, best friends Anya and Milka try to envision a free and joyful future for themselves. They spend their summers at Anya's dacha just outside of Moscow, lazing in the apple orchard, listening to Queen songs, and fantasizing about trips abroad and the lives of American teenagers. Meanwhile, Anya's parents talk about World War II, the Blockade, and the hardships they have endured.

By the time Anya and Milka are fifteen, the Soviet Empire is on the verge of collapse. They pair up with classmates Trifonov and Lopatin, and the four friends share secrets and desires, argue about history and politics, and discuss forbidden books. But the world is changing, and the fleeting time they have together is cut short by a sudden tragedy.

Years later, Anya returns to Russia from America, where she has chosen a different kind of life, far from her family and childhood friends. When she meets Lopatin again, he is a smug businessman who wants to buy her parents' dacha and cut down the apple orchard. Haunted by the ghosts of her youth, Anya comes to the stark realization that memory does not fade or disappear; rather, it moves us across time, connecting our past to our future, joys to sorrows.

Inspired by Anton Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard, Kristina Gorcheva-Newberry's The Orchard powerfully captures the lives of four Soviet teenagers who are about to lose their country and one another, and who struggle to survive, to save their friendship, to recover all that has been lost.

"Aching and sexy, clear-eyed and heartbreaking . . . an exquisite, explosive debut."-Julia Phillips, author of Disappearing Earth

Coming of age in the USSR in the 1980s, best friends Anya and Milka try to envision a free and joyful future for themselves. They spend their summers at Anya's dacha just outside of Moscow, lazing in the apple orchard, listening to Queen songs, and fantasizing about trips abroad and the lives of American teenagers. Meanwhile, Anya's parents talk about World War II, the Blockade, and the hardships they have endured.

By the time Anya and Milka are fifteen, the Soviet Empire is on the verge of collapse. They pair up with classmates Trifonov and Lopatin, and the four friends share secrets and desires, argue about history and politics, and discuss forbidden books. But the world is changing, and the fleeting time they have together is cut short by a sudden tragedy.

Years later, Anya returns to Russia from America, where she has chosen a different kind of life, far from her family and childhood friends. When she meets Lopatin again, he is a smug businessman who wants to buy her parents' dacha and cut down the apple orchard. Haunted by the ghosts of her youth, Anya comes to the stark realization that memory does not fade or disappear; rather, it moves us across time, connecting our past to our future, joys to sorrows.

Inspired by Anton Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard, Kristina Gorcheva-Newberry's The Orchard powerfully captures the lives of four Soviet teenagers who are about to lose their country and one another, and who struggle to survive, to save their friendship, to recover all that has been lost.

Editorial Reviews

1

Milka Putova and I had been friends since the first grade, which was pretty much for as long as I could remember. She was short and thin like a sprat, and every boy in our class called her exactly that-Sprat. She had small acorn-brown eyes, set too far apart and slanted-a result of one hundred and fifty years of the Tatar-Mongol yoke, as she often joked. Her face was broad and pale, her pulpy lips raspberry red, especially in winter, after we'd been sledding or building forts all afternoon, snow crusted on our knees and elbows, our bangs and eyelashes bleached with frost. We lived on the outskirts of Moscow and tramped to school together, across a vast virgin field sprawled around us like white satin. She'd walk first through knee-deep snow, wearing wool tights and felt boots, threading her legs in and out, and I'd trudge after her, stepping in her footprints. She'd halt and scribble our names in the snow with her gloved finger-Milka + Anya-and on the way back we'd rush to check whether the letters were still there.

Milka's hair was dark gold, straight and silky, cut in a neat bob around her jaw. She shampooed her hair every day, and I could smell it when we sat next to each other during classes, the delicate scent of apple blossoms resurrecting our summer months at my parents' dacha. How we'd sauntered through a corn maze, the stalks three times taller than we were, fingering green husks, separating soft, luscious silk to check on the size and ripeness of ears. Or how we roamed birch and aspen groves and gathered mushrooms for soup, their fragile trunks buried in grass, their red and orange caps burning under the trees like gems. Or how we swam in the river, racing to the other side and back and then climbing a muddy bank and drying off on towels, motionless like sunbaked frogs-bellies up.

At ten, we hadn't yet begun wearing bikini tops or shying behind bushes while changing swimsuits. We touched each other's faces, and shoulders, and nonexistent breasts, compared hands and feet, the length of our toes and fingers, noses, eyelashes, the color and shape of our nipples. We counted moles and freckles, mosquito bites and scratches, searching for hidden birthmarks, gray hairs, some sign of indisputable distinction. We lazed in a hammock, suspended between the porch railing and a single pine tree, or threaded wild strawberries on long straws and sucked them off in one ravaging movement, our tongues, our mouths magenta foam. We carved our names into birch trunks so fat, so mighty, our arms wouldn't close when we hugged them. We trapped crickets in glass jars or matchboxes, which we placed under pillows for good luck, setting the bugs free in the morning; we made wishes while watching the full moon like an amber brooch pinned low in the sky. We longed for prettier ...

Milka Putova and I had been friends since the first grade, which was pretty much for as long as I could remember. She was short and thin like a sprat, and every boy in our class called her exactly that-Sprat. She had small acorn-brown eyes, set too far apart and slanted-a result of one hundred and fifty years of the Tatar-Mongol yoke, as she often joked. Her face was broad and pale, her pulpy lips raspberry red, especially in winter, after we'd been sledding or building forts all afternoon, snow crusted on our knees and elbows, our bangs and eyelashes bleached with frost. We lived on the outskirts of Moscow and tramped to school together, across a vast virgin field sprawled around us like white satin. She'd walk first through knee-deep snow, wearing wool tights and felt boots, threading her legs in and out, and I'd trudge after her, stepping in her footprints. She'd halt and scribble our names in the snow with her gloved finger-Milka + Anya-and on the way back we'd rush to check whether the letters were still there.

Milka's hair was dark gold, straight and silky, cut in a neat bob around her jaw. She shampooed her hair every day, and I could smell it when we sat next to each other during classes, the delicate scent of apple blossoms resurrecting our summer months at my parents' dacha. How we'd sauntered through a corn maze, the stalks three times taller than we were, fingering green husks, separating soft, luscious silk to check on the size and ripeness of ears. Or how we roamed birch and aspen groves and gathered mushrooms for soup, their fragile trunks buried in grass, their red and orange caps burning under the trees like gems. Or how we swam in the river, racing to the other side and back and then climbing a muddy bank and drying off on towels, motionless like sunbaked frogs-bellies up.

At ten, we hadn't yet begun wearing bikini tops or shying behind bushes while changing swimsuits. We touched each other's faces, and shoulders, and nonexistent breasts, compared hands and feet, the length of our toes and fingers, noses, eyelashes, the color and shape of our nipples. We counted moles and freckles, mosquito bites and scratches, searching for hidden birthmarks, gray hairs, some sign of indisputable distinction. We lazed in a hammock, suspended between the porch railing and a single pine tree, or threaded wild strawberries on long straws and sucked them off in one ravaging movement, our tongues, our mouths magenta foam. We carved our names into birch trunks so fat, so mighty, our arms wouldn't close when we hugged them. We trapped crickets in glass jars or matchboxes, which we placed under pillows for good luck, setting the bugs free in the morning; we made wishes while watching the full moon like an amber brooch pinned low in the sky. We longed for prettier ...

Short Excerpt Teaser

1

Milka Putova and I had been friends since the first grade, which was pretty much for as long as I could remember. She was short and thin like a sprat, and every boy in our class called her exactly that-Sprat. She had small acorn-brown eyes, set too far apart and slanted-a result of one hundred and fifty years of the Tatar-Mongol yoke, as she often joked. Her face was broad and pale, her pulpy lips raspberry red, especially in winter, after we'd been sledding or building forts all afternoon, snow crusted on our knees and elbows, our bangs and eyelashes bleached with frost. We lived on the outskirts of Moscow and tramped to school together, across a vast virgin field sprawled around us like white satin. She'd walk first through knee-deep snow, wearing wool tights and felt boots, threading her legs in and out, and I'd trudge after her, stepping in her footprints. She'd halt and scribble our names in the snow with her gloved finger-Milka + Anya-and on the way back we'd rush to check whether the letters were still there.

Milka's hair was dark gold, straight and silky, cut in a neat bob around her jaw. She shampooed her hair every day, and I could smell it when we sat next to each other during classes, the delicate scent of apple blossoms resurrecting our summer months at my parents' dacha. How we'd sauntered through a corn maze, the stalks three times taller than we were, fingering green husks, separating soft, luscious silk to check on the size and ripeness of ears. Or how we roamed birch and aspen groves and gathered mushrooms for soup, their fragile trunks buried in grass, their red and orange caps burning under the trees like gems. Or how we swam in the river, racing to the other side and back and then climbing a muddy bank and drying off on towels, motionless like sunbaked frogs-bellies up.

At ten, we hadn't yet begun wearing bikini tops or shying behind bushes while changing swimsuits. We touched each other's faces, and shoulders, and nonexistent breasts, compared hands and feet, the length of our toes and fingers, noses, eyelashes, the color and shape of our nipples. We counted moles and freckles, mosquito bites and scratches, searching for hidden birthmarks, gray hairs, some sign of indisputable distinction. We lazed in a hammock, suspended between the porch railing and a single pine tree, or threaded wild strawberries on long straws and sucked them off in one ravaging movement, our tongues, our mouths magenta foam. We carved our names into birch trunks so fat, so mighty, our arms wouldn't close when we hugged them. We trapped crickets in glass jars or matchboxes, which we placed under pillows for good luck, setting the bugs free in the morning; we made wishes while watching the full moon like an amber brooch pinned low in the sky. We longed for prettier dresses and Zolushka's crystal shoes and a fairy godmother to turn our dingy flats into splendid castles. At the dacha, we opened the bedroom window and stared into the darkness coalescing around us. The apple trees were bearing their first tiny sour fruit. The trees swayed their branches and threw trembling shadows on the ground, and we would sprawl halfway out of the window to touch their young tender leaves.

At eleven, we still played with dolls. Some were missing limbs; others had lost lashes and hair; all had patches of skin scraped and dulled by the years of dressing and undressing, incessant bathing. We owned no male dolls but a set of tin soldiers I begged my mother to buy. The soldiers were disproportionally small, which made perfect sense to us because most of the boys in our class were shorter than the girls. We protected the soldiers fiercely, and not because they were fewer in number and cost more, but because they seemed so delicate to us and somehow helpless, in need of nurturing and reassurance. We handled the soldiers with care and stowed them in their box every evening.

Sometimes we pretended that the soldiers had just returned from the war to their wives and girlfriends. Then we would strip them naked and lay their stiff cold bodies on top of the pink plastic ones and rub the figures together as hard as we could.

"Do you think she's pregnant by now?" Milka would ask.

"Maybe. How long does it usually take?"

"Don't know. Let's rub some more," she'd say, and slide her doll back and forth under my soldier.

Oddly, I was always in charge of the males, and Milka the females. My soldier would lean in to kiss Milka's girl doll, his lips so small, so hard against her curvy painted ones. Neither tin nor plastic participant had genitals, of course, but we pretended that they did, and Milka would even take a soldier's hand and touch it to the doll's belly and legs, the thick impenetrable place in between. Or she...

Milka Putova and I had been friends since the first grade, which was pretty much for as long as I could remember. She was short and thin like a sprat, and every boy in our class called her exactly that-Sprat. She had small acorn-brown eyes, set too far apart and slanted-a result of one hundred and fifty years of the Tatar-Mongol yoke, as she often joked. Her face was broad and pale, her pulpy lips raspberry red, especially in winter, after we'd been sledding or building forts all afternoon, snow crusted on our knees and elbows, our bangs and eyelashes bleached with frost. We lived on the outskirts of Moscow and tramped to school together, across a vast virgin field sprawled around us like white satin. She'd walk first through knee-deep snow, wearing wool tights and felt boots, threading her legs in and out, and I'd trudge after her, stepping in her footprints. She'd halt and scribble our names in the snow with her gloved finger-Milka + Anya-and on the way back we'd rush to check whether the letters were still there.

Milka's hair was dark gold, straight and silky, cut in a neat bob around her jaw. She shampooed her hair every day, and I could smell it when we sat next to each other during classes, the delicate scent of apple blossoms resurrecting our summer months at my parents' dacha. How we'd sauntered through a corn maze, the stalks three times taller than we were, fingering green husks, separating soft, luscious silk to check on the size and ripeness of ears. Or how we roamed birch and aspen groves and gathered mushrooms for soup, their fragile trunks buried in grass, their red and orange caps burning under the trees like gems. Or how we swam in the river, racing to the other side and back and then climbing a muddy bank and drying off on towels, motionless like sunbaked frogs-bellies up.

At ten, we hadn't yet begun wearing bikini tops or shying behind bushes while changing swimsuits. We touched each other's faces, and shoulders, and nonexistent breasts, compared hands and feet, the length of our toes and fingers, noses, eyelashes, the color and shape of our nipples. We counted moles and freckles, mosquito bites and scratches, searching for hidden birthmarks, gray hairs, some sign of indisputable distinction. We lazed in a hammock, suspended between the porch railing and a single pine tree, or threaded wild strawberries on long straws and sucked them off in one ravaging movement, our tongues, our mouths magenta foam. We carved our names into birch trunks so fat, so mighty, our arms wouldn't close when we hugged them. We trapped crickets in glass jars or matchboxes, which we placed under pillows for good luck, setting the bugs free in the morning; we made wishes while watching the full moon like an amber brooch pinned low in the sky. We longed for prettier dresses and Zolushka's crystal shoes and a fairy godmother to turn our dingy flats into splendid castles. At the dacha, we opened the bedroom window and stared into the darkness coalescing around us. The apple trees were bearing their first tiny sour fruit. The trees swayed their branches and threw trembling shadows on the ground, and we would sprawl halfway out of the window to touch their young tender leaves.

At eleven, we still played with dolls. Some were missing limbs; others had lost lashes and hair; all had patches of skin scraped and dulled by the years of dressing and undressing, incessant bathing. We owned no male dolls but a set of tin soldiers I begged my mother to buy. The soldiers were disproportionally small, which made perfect sense to us because most of the boys in our class were shorter than the girls. We protected the soldiers fiercely, and not because they were fewer in number and cost more, but because they seemed so delicate to us and somehow helpless, in need of nurturing and reassurance. We handled the soldiers with care and stowed them in their box every evening.

Sometimes we pretended that the soldiers had just returned from the war to their wives and girlfriends. Then we would strip them naked and lay their stiff cold bodies on top of the pink plastic ones and rub the figures together as hard as we could.

"Do you think she's pregnant by now?" Milka would ask.

"Maybe. How long does it usually take?"

"Don't know. Let's rub some more," she'd say, and slide her doll back and forth under my soldier.

Oddly, I was always in charge of the males, and Milka the females. My soldier would lean in to kiss Milka's girl doll, his lips so small, so hard against her curvy painted ones. Neither tin nor plastic participant had genitals, of course, but we pretended that they did, and Milka would even take a soldier's hand and touch it to the doll's belly and legs, the thick impenetrable place in between. Or she...