Literature & Fiction

- Publisher : Ballantine Books

- Published : 25 Apr 2023

- Pages : 352

- ISBN-10 : 0593499530

- ISBN-13 : 9780593499535

- Language : English

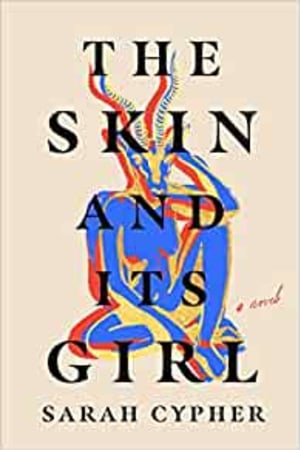

The Skin and Its Girl: A Novel

A young, queer Palestinian American woman pieces together her great-aunt's secrets in this "enchanting, memorable" (Bustle) debut, confronting questions of sexual identity, exile, and lineage.

"As beautifully detailed as a piece of Palestinian embroidery, this bold, vivid novel will speak to readers across genders, cultures, and identities."-Diana Abu-Jaber, author of Fencing with the King

In a Pacific Northwest hospital far from the Rummani family's ancestral home in Palestine, the heart of a stillborn baby begins to beat and her skin turns vibrantly, permanently cobalt blue. On the same day, the Rummanis' centuries-old soap factory in Nablus is destroyed in an air strike. The family matriarch and keeper of their lore, Aunt Nuha, believes that the blue girl embodies their sacred history, harkening back to a time when the Rummanis were among the wealthiest soap-makers and their blue soap was a symbol of a legendary love.

Decades later, Betty returns to Aunt Nuha's gravestone, faced with a difficult decision: Should she stay in the only country she's ever known, or should she follow her heart and the woman she loves, perpetuating her family's cycle of exile? Betty finds her answer in partially translated notebooks that reveal her aunt's complex life and struggle with her own sexuality, which Nuha hid to help the family immigrate to the United States. But, as Betty soon discovers, her aunt hid much more than that.

The Skin and Its Girl is a searing, poetic tale about desire and identity, and a provocative exploration of how we let stories divide, unite, and define us-and wield even the power to restore a broken family. Sarah Cypher is that rare debut novelist who writes with the mastery and flair of a seasoned storyteller.

"As beautifully detailed as a piece of Palestinian embroidery, this bold, vivid novel will speak to readers across genders, cultures, and identities."-Diana Abu-Jaber, author of Fencing with the King

In a Pacific Northwest hospital far from the Rummani family's ancestral home in Palestine, the heart of a stillborn baby begins to beat and her skin turns vibrantly, permanently cobalt blue. On the same day, the Rummanis' centuries-old soap factory in Nablus is destroyed in an air strike. The family matriarch and keeper of their lore, Aunt Nuha, believes that the blue girl embodies their sacred history, harkening back to a time when the Rummanis were among the wealthiest soap-makers and their blue soap was a symbol of a legendary love.

Decades later, Betty returns to Aunt Nuha's gravestone, faced with a difficult decision: Should she stay in the only country she's ever known, or should she follow her heart and the woman she loves, perpetuating her family's cycle of exile? Betty finds her answer in partially translated notebooks that reveal her aunt's complex life and struggle with her own sexuality, which Nuha hid to help the family immigrate to the United States. But, as Betty soon discovers, her aunt hid much more than that.

The Skin and Its Girl is a searing, poetic tale about desire and identity, and a provocative exploration of how we let stories divide, unite, and define us-and wield even the power to restore a broken family. Sarah Cypher is that rare debut novelist who writes with the mastery and flair of a seasoned storyteller.

Editorial Reviews

Postmortem

Imagine this. In the final hour before dawn, the doctor pulls a baby through an incision under a woman's belly. Everyone is doomed to this first unhousing, one way or another. And as he lifts me from the dark warmth of my mother's body and unwraps the cord from around my neck, everyone here begins to work as hard as they can. They work for several minutes, until the outcome is obvious. Someone looks at the clock, announces the time.

My mother might be to blame-she refused to push-or the doctor, so hard on himself, so ready to take responsibility for real and imagined mistakes. All their medical instruments agree: this is not a beginning, but an ending.

When my mother has been taken away, her blood still marks the floor, the room's metal surfaces, and the doctor's gown. He and the nurse, who have stayed behind to clean the body, are angry-at my mother, yes, but mostly at themselves because they made promises to her and to the adoptive parents that my birth would be routine.

But at this moment, my skin is a pallid version of my mother's wheat-colored complexion, fading to the flat yellow-gray of death. Blood vessels ruptured in my face during asphyxiation by the cord, and now, fine blue filaments around my mouth cause the doctor's hands to shake as he wipes the waxy film from behind my stiff ears. The nurse hands him another rag. When their work is finished, they will swaddle my body and offer my mother and the adoptive parents a chance to speak with the hospital's chaplain.

The doctor checks the time of death with the nurse but gets no answer.

"I said, was it six thirty-eight?"

The nurse is staring at my body with a frown.

Imagine their surprise: a vein pulses on the crown of my head. And imagine, as I have many times, the strangeness of what they see happening to my face. It is turning blue. No, not an airless blue. Like a fine network of roots, cobalt filaments are wiggling outward from lips and eyelids, webbing together under the skin across cheeks and forehead. The broken blood vessels seem to multiply with every branching. They grow in density, too, coloring my face. Down my neck, across my chest, underneath my fingernails, and between my toes. Soon my entire body is an even, lustrous blue like a creature from a fairy tale.

The nurse asks the doctor, "Have you seen anything like this before?"

Later, in his report, he will make a fuller description which will be filed away and forgotten among the handful of other strange cases in the hospital's history, reread only by me a few decades later when the hospital is about to purge its archives. But just now, he can only stare, stranded between curiosity and shock.

The nurse sets the bell of a stethoscope on my bare chest...

Imagine this. In the final hour before dawn, the doctor pulls a baby through an incision under a woman's belly. Everyone is doomed to this first unhousing, one way or another. And as he lifts me from the dark warmth of my mother's body and unwraps the cord from around my neck, everyone here begins to work as hard as they can. They work for several minutes, until the outcome is obvious. Someone looks at the clock, announces the time.

My mother might be to blame-she refused to push-or the doctor, so hard on himself, so ready to take responsibility for real and imagined mistakes. All their medical instruments agree: this is not a beginning, but an ending.

When my mother has been taken away, her blood still marks the floor, the room's metal surfaces, and the doctor's gown. He and the nurse, who have stayed behind to clean the body, are angry-at my mother, yes, but mostly at themselves because they made promises to her and to the adoptive parents that my birth would be routine.

But at this moment, my skin is a pallid version of my mother's wheat-colored complexion, fading to the flat yellow-gray of death. Blood vessels ruptured in my face during asphyxiation by the cord, and now, fine blue filaments around my mouth cause the doctor's hands to shake as he wipes the waxy film from behind my stiff ears. The nurse hands him another rag. When their work is finished, they will swaddle my body and offer my mother and the adoptive parents a chance to speak with the hospital's chaplain.

The doctor checks the time of death with the nurse but gets no answer.

"I said, was it six thirty-eight?"

The nurse is staring at my body with a frown.

Imagine their surprise: a vein pulses on the crown of my head. And imagine, as I have many times, the strangeness of what they see happening to my face. It is turning blue. No, not an airless blue. Like a fine network of roots, cobalt filaments are wiggling outward from lips and eyelids, webbing together under the skin across cheeks and forehead. The broken blood vessels seem to multiply with every branching. They grow in density, too, coloring my face. Down my neck, across my chest, underneath my fingernails, and between my toes. Soon my entire body is an even, lustrous blue like a creature from a fairy tale.

The nurse asks the doctor, "Have you seen anything like this before?"

Later, in his report, he will make a fuller description which will be filed away and forgotten among the handful of other strange cases in the hospital's history, reread only by me a few decades later when the hospital is about to purge its archives. But just now, he can only stare, stranded between curiosity and shock.

The nurse sets the bell of a stethoscope on my bare chest...

Readers Top Reviews

kathleen g

An intriguing tale of family told in the second person by Betty, who is grieving the death of her great aunt Nuha, the only person who understood her. Nuha was in the closet; Betty is both in the closet and her skin is blue. A Palestinian American, she recounts the tales she was told about Palestine and she struggles with where she fits in the world. The writing is both lush and convoluted (the second person gets tiresome) -and it takes patience. I hoped for a more plot driven novel (it's a great set up) but this circles around on itself too much for that. Thanks to Netgalley for the ARC. For fans of literary fiction.

Nancy Adair

If you are looking for a plot-driven novel that is an easy read, you can just pass this book by. If you love lush language, deep psychological exploration, a circuitous and slow reveal, and haunting characters, then, yes, this is your book. Employing folk tales and metaphor, and rich with history, this is a remarkable debut novel addressing questions of identity, heritage, love, and loyalty. The Rummani family’s stories were kept by Auntie Nuha. She rescues a newborn from being given up for adoption. The infant’s mother was depressive and separated from a husband who had betrayed her. While the child was being born, the family’s abandoned soap factory oversea in Palestine was being destroyed. The legendary soap had made the family fortune. Auntie told of a blue soap that turned girls blue, giving a heritage to the new baby whose skin was indigo. Now grown, the girl has come to her aunt’s graveside. Both women were constrained by their skin; Auntie taking on another’s identity, and the girl by the blue that set her apart. She is struggling to decide between staying with her mother or leaving with her lover. A decision that Auntie had made upon her birth, when she had planned to leave with her lover but stayed behind to care for her. “There is no truth but in old women’s tales,” the girl is told. Auntie was full of stories. Her stories interpret life and the world: the Tower of Babel, the pursuit of an elusive silver gazelle, a boy on fire saved by a girl’s rope of long hair. An admirable debut novel. I received a free egalley from the publisher through NetGalley. My review is fair and unbiased.

Short Excerpt Teaser

Postmortem

Imagine this. In the final hour before dawn, the doctor pulls a baby through an incision under a woman's belly. Everyone is doomed to this first unhousing, one way or another. And as he lifts me from the dark warmth of my mother's body and unwraps the cord from around my neck, everyone here begins to work as hard as they can. They work for several minutes, until the outcome is obvious. Someone looks at the clock, announces the time.

My mother might be to blame-she refused to push-or the doctor, so hard on himself, so ready to take responsibility for real and imagined mistakes. All their medical instruments agree: this is not a beginning, but an ending.

When my mother has been taken away, her blood still marks the floor, the room's metal surfaces, and the doctor's gown. He and the nurse, who have stayed behind to clean the body, are angry-at my mother, yes, but mostly at themselves because they made promises to her and to the adoptive parents that my birth would be routine.

But at this moment, my skin is a pallid version of my mother's wheat-colored complexion, fading to the flat yellow-gray of death. Blood vessels ruptured in my face during asphyxiation by the cord, and now, fine blue filaments around my mouth cause the doctor's hands to shake as he wipes the waxy film from behind my stiff ears. The nurse hands him another rag. When their work is finished, they will swaddle my body and offer my mother and the adoptive parents a chance to speak with the hospital's chaplain.

The doctor checks the time of death with the nurse but gets no answer.

"I said, was it six thirty-eight?"

The nurse is staring at my body with a frown.

Imagine their surprise: a vein pulses on the crown of my head. And imagine, as I have many times, the strangeness of what they see happening to my face. It is turning blue. No, not an airless blue. Like a fine network of roots, cobalt filaments are wiggling outward from lips and eyelids, webbing together under the skin across cheeks and forehead. The broken blood vessels seem to multiply with every branching. They grow in density, too, coloring my face. Down my neck, across my chest, underneath my fingernails, and between my toes. Soon my entire body is an even, lustrous blue like a creature from a fairy tale.

The nurse asks the doctor, "Have you seen anything like this before?"

Later, in his report, he will make a fuller description which will be filed away and forgotten among the handful of other strange cases in the hospital's history, reread only by me a few decades later when the hospital is about to purge its archives. But just now, he can only stare, stranded between curiosity and shock.

The nurse sets the bell of a stethoscope on my bare chest and says, "There's a heartbeat."

The doctor ignores this observation and gropes for the EEG leads. Yet no doctor in the world needs a machine to prove what anyone's eyes can see. My whole body is alive and blue: the pure cobalt of a gas flame. The color is most brilliant on my thighs, belly, and cheeks. On a normal baby, the pattern would indicate a healthy flush. My blue eyelids twitch, my blue limbs move, and I sneeze.

My birth comes over two centuries after our family first exalted the glories of the color blue, Auntie, but you taught me a few rules of interpretation. Everything depends on context. I will get around to why I am here at your gravestone, but first, let me try again to understand how you came to my bassinet on my first day in this world.

You taught me stories so old they were last repeated when today's aunties' aunties were still small enough to run barefoot around the soap factory. The curse of the despicable woman, they said, is to give birth to stones, to puppies, to a piece of cannibalistic dung. In that world, there are crones and magic rings, red-eyed ogres and water-dwelling djinn. Back then, everybody knew that Aladdin meant the Glory of Religion (Ala' ad-Din, if you want to break it down) and that every tale is an allegory.

To be clear, ours was no longer that world.

Yet we found ourselves one day with an uncanny pure thing on the top floor of a middling Portland hospital. Here we had, somehow, me-a blue baby-and, soon, three fairy godmothers.

Births in the Rummani family had always been newsworthy, so it was unusual, that morning, for only one blood relative to attend: my maternal grandmother, Saeeda Rummani. During my nine months in utero there had been a divorce, the resurgence of a mental illness, the decision to give a baby away, even a lie about a miscarriage-nothing to be proud of. The birth deserved no pomp, and Saeeda had left her husband in the care of his home nurse and gone, without muc...

Imagine this. In the final hour before dawn, the doctor pulls a baby through an incision under a woman's belly. Everyone is doomed to this first unhousing, one way or another. And as he lifts me from the dark warmth of my mother's body and unwraps the cord from around my neck, everyone here begins to work as hard as they can. They work for several minutes, until the outcome is obvious. Someone looks at the clock, announces the time.

My mother might be to blame-she refused to push-or the doctor, so hard on himself, so ready to take responsibility for real and imagined mistakes. All their medical instruments agree: this is not a beginning, but an ending.

When my mother has been taken away, her blood still marks the floor, the room's metal surfaces, and the doctor's gown. He and the nurse, who have stayed behind to clean the body, are angry-at my mother, yes, but mostly at themselves because they made promises to her and to the adoptive parents that my birth would be routine.

But at this moment, my skin is a pallid version of my mother's wheat-colored complexion, fading to the flat yellow-gray of death. Blood vessels ruptured in my face during asphyxiation by the cord, and now, fine blue filaments around my mouth cause the doctor's hands to shake as he wipes the waxy film from behind my stiff ears. The nurse hands him another rag. When their work is finished, they will swaddle my body and offer my mother and the adoptive parents a chance to speak with the hospital's chaplain.

The doctor checks the time of death with the nurse but gets no answer.

"I said, was it six thirty-eight?"

The nurse is staring at my body with a frown.

Imagine their surprise: a vein pulses on the crown of my head. And imagine, as I have many times, the strangeness of what they see happening to my face. It is turning blue. No, not an airless blue. Like a fine network of roots, cobalt filaments are wiggling outward from lips and eyelids, webbing together under the skin across cheeks and forehead. The broken blood vessels seem to multiply with every branching. They grow in density, too, coloring my face. Down my neck, across my chest, underneath my fingernails, and between my toes. Soon my entire body is an even, lustrous blue like a creature from a fairy tale.

The nurse asks the doctor, "Have you seen anything like this before?"

Later, in his report, he will make a fuller description which will be filed away and forgotten among the handful of other strange cases in the hospital's history, reread only by me a few decades later when the hospital is about to purge its archives. But just now, he can only stare, stranded between curiosity and shock.

The nurse sets the bell of a stethoscope on my bare chest and says, "There's a heartbeat."

The doctor ignores this observation and gropes for the EEG leads. Yet no doctor in the world needs a machine to prove what anyone's eyes can see. My whole body is alive and blue: the pure cobalt of a gas flame. The color is most brilliant on my thighs, belly, and cheeks. On a normal baby, the pattern would indicate a healthy flush. My blue eyelids twitch, my blue limbs move, and I sneeze.

My birth comes over two centuries after our family first exalted the glories of the color blue, Auntie, but you taught me a few rules of interpretation. Everything depends on context. I will get around to why I am here at your gravestone, but first, let me try again to understand how you came to my bassinet on my first day in this world.

You taught me stories so old they were last repeated when today's aunties' aunties were still small enough to run barefoot around the soap factory. The curse of the despicable woman, they said, is to give birth to stones, to puppies, to a piece of cannibalistic dung. In that world, there are crones and magic rings, red-eyed ogres and water-dwelling djinn. Back then, everybody knew that Aladdin meant the Glory of Religion (Ala' ad-Din, if you want to break it down) and that every tale is an allegory.

To be clear, ours was no longer that world.

Yet we found ourselves one day with an uncanny pure thing on the top floor of a middling Portland hospital. Here we had, somehow, me-a blue baby-and, soon, three fairy godmothers.

Births in the Rummani family had always been newsworthy, so it was unusual, that morning, for only one blood relative to attend: my maternal grandmother, Saeeda Rummani. During my nine months in utero there had been a divorce, the resurgence of a mental illness, the decision to give a baby away, even a lie about a miscarriage-nothing to be proud of. The birth deserved no pomp, and Saeeda had left her husband in the care of his home nurse and gone, without muc...