Genre Fiction

- Publisher : One World

- Published : 28 Mar 2023

- Pages : 304

- ISBN-10 : 052551208X

- ISBN-13 : 9780525512080

- Language : English

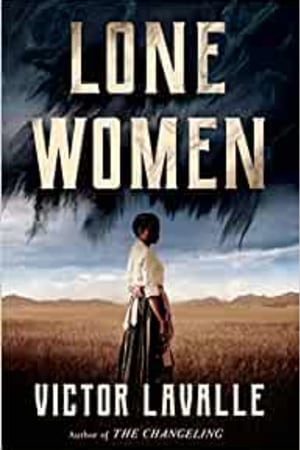

Lone Women: A Novel

Blue skies, empty land-and enough wide-open space to hide a horrifying secret. A woman with a past, a mysterious trunk, a town on the edge of nowhere, and a bracing new vision of the American West, from the award-winning author of The Changeling.

"If the literary gods mixed together Haruki Murakami and Ralph Ellison, the result would be Victor LaValle."-Anthony Doerr, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of All the Light We Cannot See

ONE OF THE MOST ANTICIPATED BOOKS OF 2023: The New York Times, Time, Oprah Daily, Los Angeles Times, Esquire, Essence, Salon, Vulture, Reader's Digest, The Root, LitHub, Paste, PopSugar, Chicago Review of Books, BookPage, Book Riot, Tordotcom, Crime Reads, Kirkus Reviews

Adelaide Henry carries an enormous steamer trunk with her wherever she goes. It's locked at all times. Because when the trunk opens, people around Adelaide start to disappear.

The year is 1915, and Adelaide is in trouble. Her secret sin killed her parents, forcing her to flee California in a hellfire rush and make her way to Montana as a homesteader. Dragging the trunk with her at every stop, she will become one of the "lone women" taking advantage of the government's offer of free land for those who can tame it-except that Adelaide isn't alone. And the secret she's tried so desperately to lock away might be the only thing that will help her survive the harsh territory.

Crafted by a modern master of magical suspense, Lone Women blends shimmering prose, an unforgettable cast of adventurers who find horror and sisterhood in a brutal landscape, and a portrait of early-twentieth-century America like you've never seen. And at its heart is the gripping story of a woman desperate to bury her past-or redeem it.

"If the literary gods mixed together Haruki Murakami and Ralph Ellison, the result would be Victor LaValle."-Anthony Doerr, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of All the Light We Cannot See

ONE OF THE MOST ANTICIPATED BOOKS OF 2023: The New York Times, Time, Oprah Daily, Los Angeles Times, Esquire, Essence, Salon, Vulture, Reader's Digest, The Root, LitHub, Paste, PopSugar, Chicago Review of Books, BookPage, Book Riot, Tordotcom, Crime Reads, Kirkus Reviews

Adelaide Henry carries an enormous steamer trunk with her wherever she goes. It's locked at all times. Because when the trunk opens, people around Adelaide start to disappear.

The year is 1915, and Adelaide is in trouble. Her secret sin killed her parents, forcing her to flee California in a hellfire rush and make her way to Montana as a homesteader. Dragging the trunk with her at every stop, she will become one of the "lone women" taking advantage of the government's offer of free land for those who can tame it-except that Adelaide isn't alone. And the secret she's tried so desperately to lock away might be the only thing that will help her survive the harsh territory.

Crafted by a modern master of magical suspense, Lone Women blends shimmering prose, an unforgettable cast of adventurers who find horror and sisterhood in a brutal landscape, and a portrait of early-twentieth-century America like you've never seen. And at its heart is the gripping story of a woman desperate to bury her past-or redeem it.

Editorial Reviews

1

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who live with shame, and those who die from it. On Tuesday, Adelaide Henry would've called herself the former, but by Wednesday she wasn't as sure. If she was trying to live, then why would she be walking through her family's farmhouse carrying an Atlas jar of gasoline, pouring that gasoline on the kitchen floor, the dining table, dousing the settee in the den? And after she emptied the first Atlas jar, why go back to the kitchen for the other jar, then climb the stairs to the second floor, listening to the splash of gasoline on every step? Was she planning to live, or trying to die?

There were twenty-seven Black farming families in California's Lucerne Valley in 1915. Adelaide and her parents had been one of them. After today there would only be twenty-six.

Adelaide reached the second-floor landing. She hardly smelled the gasoline anymore. Her hands were covered in fresh wounds, but she felt no pain. There were two bedrooms on the second floor: her bedroom and her parents'.

Adelaide's parents were lured west by the promise of land in this valley. The federal government encouraged Americans to homestead California. The native population had been decimated, cleared off the property. Now it was time to give it all away. This invitation was one of the few that the United States extended to even its Negro citizens, and after 1866, the African Society put out a call to "colonize" Southern California. The Henrys were among the hundreds who came. They weren't going to get a fair shot in Arkansas, that was for damn sure. The federal government called this homesteading.

Glenville and Eleanor Henry fled to California and grew alfalfa and wild grass, sold it to cattle owners for feed. Glenville studied the work of Luther Burbank and in 1908 they began growing the botanist's Santa Rosa plums. To Adelaide the fruit tasted of sugar and self-determination. Adelaide had worked the orchards and fields alongside her daddy since she was twelve. Labored in the kitchen and the barn with her mother for even longer. Thirty-one years of life on this farm. Thirty-one.

And now she would burn it all down.

"Ma'am?"

Adelaide startled at the sound of the wagon man.

"Good Lord, what is that smell?"

He stood at the front entrance, separated from the interior by a screen door and nothing more. Adelaide stood upstairs, at the threshold of her parents' bedroom. The half-full Atlas jar wobbled in her grip. She turned and called over the landing.

"Mr. Cole, I will be out in five minutes."

She couldn't see him, but she heard him. The grumble of an old Black man, barely audible but somehow still as loud as a thunderclap. It reminded her of her father.

...

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who live with shame, and those who die from it. On Tuesday, Adelaide Henry would've called herself the former, but by Wednesday she wasn't as sure. If she was trying to live, then why would she be walking through her family's farmhouse carrying an Atlas jar of gasoline, pouring that gasoline on the kitchen floor, the dining table, dousing the settee in the den? And after she emptied the first Atlas jar, why go back to the kitchen for the other jar, then climb the stairs to the second floor, listening to the splash of gasoline on every step? Was she planning to live, or trying to die?

There were twenty-seven Black farming families in California's Lucerne Valley in 1915. Adelaide and her parents had been one of them. After today there would only be twenty-six.

Adelaide reached the second-floor landing. She hardly smelled the gasoline anymore. Her hands were covered in fresh wounds, but she felt no pain. There were two bedrooms on the second floor: her bedroom and her parents'.

Adelaide's parents were lured west by the promise of land in this valley. The federal government encouraged Americans to homestead California. The native population had been decimated, cleared off the property. Now it was time to give it all away. This invitation was one of the few that the United States extended to even its Negro citizens, and after 1866, the African Society put out a call to "colonize" Southern California. The Henrys were among the hundreds who came. They weren't going to get a fair shot in Arkansas, that was for damn sure. The federal government called this homesteading.

Glenville and Eleanor Henry fled to California and grew alfalfa and wild grass, sold it to cattle owners for feed. Glenville studied the work of Luther Burbank and in 1908 they began growing the botanist's Santa Rosa plums. To Adelaide the fruit tasted of sugar and self-determination. Adelaide had worked the orchards and fields alongside her daddy since she was twelve. Labored in the kitchen and the barn with her mother for even longer. Thirty-one years of life on this farm. Thirty-one.

And now she would burn it all down.

"Ma'am?"

Adelaide startled at the sound of the wagon man.

"Good Lord, what is that smell?"

He stood at the front entrance, separated from the interior by a screen door and nothing more. Adelaide stood upstairs, at the threshold of her parents' bedroom. The half-full Atlas jar wobbled in her grip. She turned and called over the landing.

"Mr. Cole, I will be out in five minutes."

She couldn't see him, but she heard him. The grumble of an old Black man, barely audible but somehow still as loud as a thunderclap. It reminded her of her father.

...

Short Excerpt Teaser

1

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who live with shame, and those who die from it. On Tuesday, Adelaide Henry would've called herself the former, but by Wednesday she wasn't as sure. If she was trying to live, then why would she be walking through her family's farmhouse carrying an Atlas jar of gasoline, pouring that gasoline on the kitchen floor, the dining table, dousing the settee in the den? And after she emptied the first Atlas jar, why go back to the kitchen for the other jar, then climb the stairs to the second floor, listening to the splash of gasoline on every step? Was she planning to live, or trying to die?

There were twenty-seven Black farming families in California's Lucerne Valley in 1915. Adelaide and her parents had been one of them. After today there would only be twenty-six.

Adelaide reached the second-floor landing. She hardly smelled the gasoline anymore. Her hands were covered in fresh wounds, but she felt no pain. There were two bedrooms on the second floor: her bedroom and her parents'.

Adelaide's parents were lured west by the promise of land in this valley. The federal government encouraged Americans to homestead California. The native population had been decimated, cleared off the property. Now it was time to give it all away. This invitation was one of the few that the United States extended to even its Negro citizens, and after 1866, the African Society put out a call to "colonize" Southern California. The Henrys were among the hundreds who came. They weren't going to get a fair shot in Arkansas, that was for damn sure. The federal government called this homesteading.

Glenville and Eleanor Henry fled to California and grew alfalfa and wild grass, sold it to cattle owners for feed. Glenville studied the work of Luther Burbank and in 1908 they began growing the botanist's Santa Rosa plums. To Adelaide the fruit tasted of sugar and self-determination. Adelaide had worked the orchards and fields alongside her daddy since she was twelve. Labored in the kitchen and the barn with her mother for even longer. Thirty-one years of life on this farm. Thirty-one.

And now she would burn it all down.

"Ma'am?"

Adelaide startled at the sound of the wagon man.

"Good Lord, what is that smell?"

He stood at the front entrance, separated from the interior by a screen door and nothing more. Adelaide stood upstairs, at the threshold of her parents' bedroom. The half-full Atlas jar wobbled in her grip. She turned and called over the landing.

"Mr. Cole, I will be out in five minutes."

She couldn't see him, but she heard him. The grumble of an old Black man, barely audible but somehow still as loud as a thunderclap. It reminded her of her father.

"That's what you said five minutes ago!"

Adelaide heard the creak of the screen door's springs. A vision flashed before her: Mr. Cole coming to the foot of the stairs and Adelaide dumping the remaining gasoline right onto his head; Adelaide reaching for the matches that were in her pocket; lighting one and dropping it right onto Mr. Cole. Then, combustion.

But she didn't want to kill this old man, so she called out to him instead.

"Have you got my trunk into the wagon yet?" she called.

Quiet, quiet.

Then the sigh of the screen door being released. He hadn't stepped inside. He called to her again from the porch.

"I tried," he said. "But that thing weighs more than my damn horse. What did you pack inside?"

My whole life, she thought. Everything that still matters.

She looked to the door of her parents' bedroom, then called down one more time.

"Five minutes, Mr. Cole. We'll get the trunk in the wagon together."

Another grumble but he didn't curse her and she didn't hear the sound of his wagon's wheels riding off. For a man like Mr. Cole, that was as close to an "okay" as she was going to get.

Would she really have set him on fire? She couldn't say. But it's startling what people will do when they are desperate.

Adelaide Henry turned the handle to her parents' bedroom and stepped inside and shut the door behind her and stood in the silence and the dark. The heavy curtains were pulled shut. She'd done that at dawn. After she'd dragged the bodies of Glenville and Eleanor inside and put them to bed.

They lay together now, in their marriage bed. The same place where Adelaide had been conceived. They were only shapes, because she'd thrown a sheet over their corpses. Their blood had soaked through. The outline of their bodies appeared as red silhouettes.

She went to her father's side. The fabric had adhered to his skin when the blood dried. She'd pulled the sheet up over his head...

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who live with shame, and those who die from it. On Tuesday, Adelaide Henry would've called herself the former, but by Wednesday she wasn't as sure. If she was trying to live, then why would she be walking through her family's farmhouse carrying an Atlas jar of gasoline, pouring that gasoline on the kitchen floor, the dining table, dousing the settee in the den? And after she emptied the first Atlas jar, why go back to the kitchen for the other jar, then climb the stairs to the second floor, listening to the splash of gasoline on every step? Was she planning to live, or trying to die?

There were twenty-seven Black farming families in California's Lucerne Valley in 1915. Adelaide and her parents had been one of them. After today there would only be twenty-six.

Adelaide reached the second-floor landing. She hardly smelled the gasoline anymore. Her hands were covered in fresh wounds, but she felt no pain. There were two bedrooms on the second floor: her bedroom and her parents'.

Adelaide's parents were lured west by the promise of land in this valley. The federal government encouraged Americans to homestead California. The native population had been decimated, cleared off the property. Now it was time to give it all away. This invitation was one of the few that the United States extended to even its Negro citizens, and after 1866, the African Society put out a call to "colonize" Southern California. The Henrys were among the hundreds who came. They weren't going to get a fair shot in Arkansas, that was for damn sure. The federal government called this homesteading.

Glenville and Eleanor Henry fled to California and grew alfalfa and wild grass, sold it to cattle owners for feed. Glenville studied the work of Luther Burbank and in 1908 they began growing the botanist's Santa Rosa plums. To Adelaide the fruit tasted of sugar and self-determination. Adelaide had worked the orchards and fields alongside her daddy since she was twelve. Labored in the kitchen and the barn with her mother for even longer. Thirty-one years of life on this farm. Thirty-one.

And now she would burn it all down.

"Ma'am?"

Adelaide startled at the sound of the wagon man.

"Good Lord, what is that smell?"

He stood at the front entrance, separated from the interior by a screen door and nothing more. Adelaide stood upstairs, at the threshold of her parents' bedroom. The half-full Atlas jar wobbled in her grip. She turned and called over the landing.

"Mr. Cole, I will be out in five minutes."

She couldn't see him, but she heard him. The grumble of an old Black man, barely audible but somehow still as loud as a thunderclap. It reminded her of her father.

"That's what you said five minutes ago!"

Adelaide heard the creak of the screen door's springs. A vision flashed before her: Mr. Cole coming to the foot of the stairs and Adelaide dumping the remaining gasoline right onto his head; Adelaide reaching for the matches that were in her pocket; lighting one and dropping it right onto Mr. Cole. Then, combustion.

But she didn't want to kill this old man, so she called out to him instead.

"Have you got my trunk into the wagon yet?" she called.

Quiet, quiet.

Then the sigh of the screen door being released. He hadn't stepped inside. He called to her again from the porch.

"I tried," he said. "But that thing weighs more than my damn horse. What did you pack inside?"

My whole life, she thought. Everything that still matters.

She looked to the door of her parents' bedroom, then called down one more time.

"Five minutes, Mr. Cole. We'll get the trunk in the wagon together."

Another grumble but he didn't curse her and she didn't hear the sound of his wagon's wheels riding off. For a man like Mr. Cole, that was as close to an "okay" as she was going to get.

Would she really have set him on fire? She couldn't say. But it's startling what people will do when they are desperate.

Adelaide Henry turned the handle to her parents' bedroom and stepped inside and shut the door behind her and stood in the silence and the dark. The heavy curtains were pulled shut. She'd done that at dawn. After she'd dragged the bodies of Glenville and Eleanor inside and put them to bed.

They lay together now, in their marriage bed. The same place where Adelaide had been conceived. They were only shapes, because she'd thrown a sheet over their corpses. Their blood had soaked through. The outline of their bodies appeared as red silhouettes.

She went to her father's side. The fabric had adhered to his skin when the blood dried. She'd pulled the sheet up over his head...