Fantasy

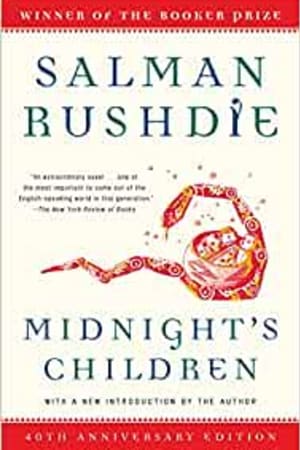

- Publisher : Random House Trade Paperbacks; 25th Anniversary edition

- Published : 04 Apr 2006

- Pages : 536

- ISBN-10 : 0812976533

- ISBN-13 : 9780812976533

- Language : English

Midnight's Children: A Novel (Modern Library 100 Best Novels)

The iconic masterpiece of India that introduced the world to "a glittering novelist-one with startling imaginative and intellectual resources, a master of perpetual storytelling" (The New Yorker)

WINNER OF THE BEST OF THE BOOKERS • SOON TO BE A NETFLIX ORIGINAL SERIES

Selected by the Modern Library as one of the 100 best novels of all time • The fortieth anniversary edition, featuring a new introduction by the author

Saleem Sinai is born at the stroke of midnight on August 15, 1947, the very moment of India's independence. Greeted by fireworks displays, cheering crowds, and Prime Minister Nehru himself, Saleem grows up to learn the ominous consequences of this coincidence. His every act is mirrored and magnified in events that sway the course of national affairs; his health and well-being are inextricably bound to those of his nation; his life is inseparable, at times indistinguishable, from the history of his country. Perhaps most remarkable are the telepathic powers linking him with India's 1,000 other "midnight's children," all born in that initial hour and endowed with magical gifts.

This novel is at once a fascinating family saga and an astonishing evocation of a vast land and its people–a brilliant incarnation of the universal human comedy. Forty years after its publication, Midnight's Children stands apart as both an epochal work of fiction and a brilliant performance by one of the great literary voices of our time.

WINNER OF THE BEST OF THE BOOKERS • SOON TO BE A NETFLIX ORIGINAL SERIES

Selected by the Modern Library as one of the 100 best novels of all time • The fortieth anniversary edition, featuring a new introduction by the author

Saleem Sinai is born at the stroke of midnight on August 15, 1947, the very moment of India's independence. Greeted by fireworks displays, cheering crowds, and Prime Minister Nehru himself, Saleem grows up to learn the ominous consequences of this coincidence. His every act is mirrored and magnified in events that sway the course of national affairs; his health and well-being are inextricably bound to those of his nation; his life is inseparable, at times indistinguishable, from the history of his country. Perhaps most remarkable are the telepathic powers linking him with India's 1,000 other "midnight's children," all born in that initial hour and endowed with magical gifts.

This novel is at once a fascinating family saga and an astonishing evocation of a vast land and its people–a brilliant incarnation of the universal human comedy. Forty years after its publication, Midnight's Children stands apart as both an epochal work of fiction and a brilliant performance by one of the great literary voices of our time.

Editorial Reviews

"Extraordinary . . . one of the most important [novels] to come out of the English-speaking world in this generation."

–The New York Review of Books

"The literary map of India is about to be redrawn. . . . Midnight's Children sounds like a continent finding its voice."

–The New York Times

"In Salman Rushdie, India has produced a glittering novelist– one with startling imaginative and intellectual resources, a master of perpetual storytelling."

–The New Yorker

"A marvelous epic . . . Rushdie's prose snaps into playback and flash-forward . . . stopping on images, vistas, and characters of unforgettable presence. Their range is as rich as India herself."

–Newsweek

"Burgeons with life, with exuberance and fantasy . . . Rushdie is a writer of courage, impressive strength, and sheer stylistic brilliance."

–The Washington Post Book World

"Pure story–an ebullient, wildly clowning, satirical, descriptively witty charge of energy."

–Chicago Sun-Times

–The New York Review of Books

"The literary map of India is about to be redrawn. . . . Midnight's Children sounds like a continent finding its voice."

–The New York Times

"In Salman Rushdie, India has produced a glittering novelist– one with startling imaginative and intellectual resources, a master of perpetual storytelling."

–The New Yorker

"A marvelous epic . . . Rushdie's prose snaps into playback and flash-forward . . . stopping on images, vistas, and characters of unforgettable presence. Their range is as rich as India herself."

–Newsweek

"Burgeons with life, with exuberance and fantasy . . . Rushdie is a writer of courage, impressive strength, and sheer stylistic brilliance."

–The Washington Post Book World

"Pure story–an ebullient, wildly clowning, satirical, descriptively witty charge of energy."

–Chicago Sun-Times

Readers Top Reviews

Hungry SpongeS. Horn

Ok, it is not an easy read but then again its not a hard read, it just happens to be a brilliant work of fiction that requires some perseverance, mainly to accept the magical realism that twines around the historical and personal stories. Rushdie is certainly a Marmite author, in this work his storytelling gifts are outstanding and his language at times elaborate and meandering, but for me thats the challenge and beauty of his style. The display of imagination in structuring the tale is breathtaking and whilst the pace slows at times, it hangs together to keep the pages turning. My advice would be to give it a go, if it works for you then you'll have discovered a gem, if it doesnt then at least you can constructively critique the most famous Booker of them all.

Aravind

This winner of the "Booker of Bookers" is a difficult book to read, and a far more difficult one to rate. It frustrated me to no end with the meandering narrative that required me to re-re-read several paragraphs quite frequently and an unusual literary style that challenged my comprehension. The only motivation for me to persevere with it was the magic Mr. Rushdie has made with the words; almost every sentence from this book is eminently quotable! It certainly demands another reading, which I hope to give it, in the not-far-away future.

Kindle

I read Midnight’s Children as it’s one of those books on all those lists of books one should read. I grew up with this book featuring in the news and in the papers and I think I must have built up some kind of legend around it, thought of it as too weighty, too hard, too important to be a reading experience I could immerse myself in. I’m glad I gave it a go. Yes, it still feels important but it’s a good read. It’s a clever mix of history, magical realism and family saga. It’s true escapism at times and horrifying reality at others. Despite the multitudinous characters and the incredible vocabulary, I followed the narrative, the themes, the imagery and it didn’t feel like hard work. I liked the element of an unreliable narrator and the references to storytelling, whose truth is passed on, what we choose to reveal, what we embellish, what we forget or misremember. Padma’s role was key to grounding things and sometimes speaking my own thoughts out loud. It’s epic and has taken me an absolute age to read, maybe because it’s so dense. Maybe because I’m an idiot. Feeling stupid can be humbling though and there’s value to be found in wading slowly through a well thought out novel rather than zooming through a trashy novel. Was it necessary to use a little used fancy word in place of something that would be more accessible and easy to read? It’s a writer’s book not a marketing brochure or piece of journalism so yes, there is absolutely a place on my bookshelves for work that challenges me, opens my mind, introduces new vocabulary. I often write notes on books as I read them but with Midnight’s Children I just soaked it all up. Knowing it’s often a set text made me wary of over analysing as I read it. Studying English Literature in university momentarily killed my devouring of fiction. Over analysing killed the enjoyment of it and the looming essays tainted my reading time. Not so now. Reading the one star reviews on here I’d say that clearly it’s not for everyone, if you’re looking for a page turning historical romp, this is not it. It’s a different genre. It put me in mind of the Gabriel Garcia Marquez literary vibe.

Sandra Wick

Rushdie's books are always a challenge and this one was the hardest one that I have read. That being said, he gives excellent views on the Asian world from a personal standpoint. His narrative about the birth of Indian and Pakistan were very vivid and revealing to someone who has just read a few lines in a history book about these major events. He had covered living in every place from a well-to-do home to a slum shack. He makes allusions back and forth in time that can be confusing. Despite it being a labor to get through it, after I finished this book, I appreciated it for being an amazing narrative.

Bill from PhillySara

I had to give it up after 45 pages. From the awards and reviews I was expecting a serious book about a serious country in a serious time. If you don't know, this book is mostly whimsy, odd humor, farce and inability to move the story. I'm sure Rushdie was in stitches as he wrote each page but his humor escapes me. If you want to read about a doctor with a huge nose, a hypochondriac woman who for modesty's sake must be examined through a hole in a draped sheet, a boatman who never bathes and a group of elders that use a spittoon from great distances, then this is your book. It isn't mine. If you want to read a very good book with Muslim mysticism try "Alif the Unseen."

Short Excerpt Teaser

The Perforated Sheet

I WAS BORN in the city of Bombay … once upon a time. No, that won't do, there's no getting away from the date: I was born in Doctor Narlikar's Nursing Home on August 15th, 1947. And the time? The time matters, too. Well then: at night. No, it's important to be more … On the stroke of midnight, as a matter of fact. Clock-hands joined palms in respectful greeting as I came. Oh, spell it out, spell it out: at the precise instant of India's arrival at independence, I tumbled forth into the world. There were gasps. And, outside the window, fireworks and crowds. A few seconds later, my father broke his big toe; but his accident was a mere trifle when set beside what had befallen me in that benighted moment, because thanks to the occult tyrannies of those blandly saluting clocks I had been mysteriously handcuffed to history, my destinies indissolubly chained to those of my country. For the next three decades, there was to be no escape. Soothsayers had prophesied me, newspapers celebrated my arrival, politicos ratified my authenticity. I was left entirely without a say in the matter. I, Saleem Sinai, later variously called Snotnose, Stainface, Baldy, Sniffer, Buddha and even Piece-of-the-Moon, had become heavily embroiled in Fate-at the best of times a dangerous sort of involvement. And I couldn't even wipe my own nose at the time.

Now, however, time (having no further use for me) is running out. I will soon be thirty-one years old. Perhaps. If my crumbling, overused body permits. But I have no hope of saving my life, nor can I count on having even a thousand nights and a night. I must work fast, faster than Scheherazade, if I am to end up meaning-yes, meaning- something. I admit it: above all things, I fear absurdity.

And there are so many stories to tell, too many, such an excess of intertwined lives events miracles places rumors, so dense a commingling of the improbable and the mundane! I have been a swallower of lives; and to know me, just the one of me, you'll have to swallow the lot as well. Consumed multitudes are jostling and shoving inside me; and guided only by the memory of a large white bedsheet with a roughly circular hole some seven inches in diameter cut into the center, clutching at the dream of that holey, mutilated square of linen, which is my talisman, my open-sesame, I must commence the business of remaking my life from the point at which it really began, some thirty-two years before anything as obvious, as present, as my clock-ridden, crime-stained birth.

(The sheet, incidentally, is stained too, with three drops of old, faded redness. As the Quran tells us: Recite, in the name of the Lord thy Creator, who created Man from clots of blood.)

One Kashmiri morning in the early spring of 1915, my grandfather Aadam Aziz hit his nose against a frost-hardened tussock of earth while attempting to pray. Three drops of blood plopped out of his left nostril, hardened instantly in the brittle air and lay before his eyes on the prayer-mat, transformed into rubies. Lurching back until he knelt with his head once more upright, he found that the tears which had sprung to his eyes had solidified, too; and at that moment, as he brushed diamonds contemptuously from his lashes, he resolved never again to kiss earth for any god or man. This decision, however, made a hole in him, a vacancy in a vital inner chamber, leaving him vulnerable to women and history. Unaware of this at first, despite his recently completed medical training, he stood up, rolled the prayer-mat into a thick cheroot, and holding it under his right arm surveyed the valley through clear, diamond-free eyes.

The world was new again. After a winter's gestation in its eggshell of ice, the valley had beaked its way out into the open, moist and yellow. The new grass bided its time underground; the mountains were retreating to their hill-stations for the warm season. (In the winter, when the valley shrank under the ice, the mountains closed in and snarled like angry jaws around the city on the lake.)

In those days the radio mast had not been built and the temple of Sankara Acharya, a little black blister on a khaki hill, still dominated the streets and lake of Srinagar. In those days there was no army camp at the lakeside, no endless snakes of camouflaged trucks and jeeps clogged the narrow mountain roads, no soldiers hid behind the crests of the mountains past Baramulla and Gulmarg. In those days travellers were not shot as spies if they took photographs of bridges, and apart from the Englishmen's houseboats on the lake, the valley had hardly changed since the Mughal Empire, for all its springtime renewals; but my grandfather's eyes-which were, like the rest o...

I WAS BORN in the city of Bombay … once upon a time. No, that won't do, there's no getting away from the date: I was born in Doctor Narlikar's Nursing Home on August 15th, 1947. And the time? The time matters, too. Well then: at night. No, it's important to be more … On the stroke of midnight, as a matter of fact. Clock-hands joined palms in respectful greeting as I came. Oh, spell it out, spell it out: at the precise instant of India's arrival at independence, I tumbled forth into the world. There were gasps. And, outside the window, fireworks and crowds. A few seconds later, my father broke his big toe; but his accident was a mere trifle when set beside what had befallen me in that benighted moment, because thanks to the occult tyrannies of those blandly saluting clocks I had been mysteriously handcuffed to history, my destinies indissolubly chained to those of my country. For the next three decades, there was to be no escape. Soothsayers had prophesied me, newspapers celebrated my arrival, politicos ratified my authenticity. I was left entirely without a say in the matter. I, Saleem Sinai, later variously called Snotnose, Stainface, Baldy, Sniffer, Buddha and even Piece-of-the-Moon, had become heavily embroiled in Fate-at the best of times a dangerous sort of involvement. And I couldn't even wipe my own nose at the time.

Now, however, time (having no further use for me) is running out. I will soon be thirty-one years old. Perhaps. If my crumbling, overused body permits. But I have no hope of saving my life, nor can I count on having even a thousand nights and a night. I must work fast, faster than Scheherazade, if I am to end up meaning-yes, meaning- something. I admit it: above all things, I fear absurdity.

And there are so many stories to tell, too many, such an excess of intertwined lives events miracles places rumors, so dense a commingling of the improbable and the mundane! I have been a swallower of lives; and to know me, just the one of me, you'll have to swallow the lot as well. Consumed multitudes are jostling and shoving inside me; and guided only by the memory of a large white bedsheet with a roughly circular hole some seven inches in diameter cut into the center, clutching at the dream of that holey, mutilated square of linen, which is my talisman, my open-sesame, I must commence the business of remaking my life from the point at which it really began, some thirty-two years before anything as obvious, as present, as my clock-ridden, crime-stained birth.

(The sheet, incidentally, is stained too, with three drops of old, faded redness. As the Quran tells us: Recite, in the name of the Lord thy Creator, who created Man from clots of blood.)

One Kashmiri morning in the early spring of 1915, my grandfather Aadam Aziz hit his nose against a frost-hardened tussock of earth while attempting to pray. Three drops of blood plopped out of his left nostril, hardened instantly in the brittle air and lay before his eyes on the prayer-mat, transformed into rubies. Lurching back until he knelt with his head once more upright, he found that the tears which had sprung to his eyes had solidified, too; and at that moment, as he brushed diamonds contemptuously from his lashes, he resolved never again to kiss earth for any god or man. This decision, however, made a hole in him, a vacancy in a vital inner chamber, leaving him vulnerable to women and history. Unaware of this at first, despite his recently completed medical training, he stood up, rolled the prayer-mat into a thick cheroot, and holding it under his right arm surveyed the valley through clear, diamond-free eyes.

The world was new again. After a winter's gestation in its eggshell of ice, the valley had beaked its way out into the open, moist and yellow. The new grass bided its time underground; the mountains were retreating to their hill-stations for the warm season. (In the winter, when the valley shrank under the ice, the mountains closed in and snarled like angry jaws around the city on the lake.)

In those days the radio mast had not been built and the temple of Sankara Acharya, a little black blister on a khaki hill, still dominated the streets and lake of Srinagar. In those days there was no army camp at the lakeside, no endless snakes of camouflaged trucks and jeeps clogged the narrow mountain roads, no soldiers hid behind the crests of the mountains past Baramulla and Gulmarg. In those days travellers were not shot as spies if they took photographs of bridges, and apart from the Englishmen's houseboats on the lake, the valley had hardly changed since the Mughal Empire, for all its springtime renewals; but my grandfather's eyes-which were, like the rest o...