Sociology

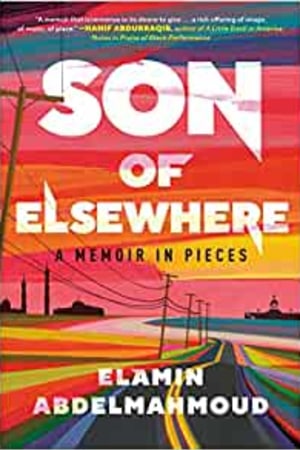

- Publisher : Ballantine Books

- Published : 17 May 2022

- Pages : 288

- ISBN-10 : 059349685X

- ISBN-13 : 9780593496855

- Language : English

Son of Elsewhere: A Memoir in Pieces

An enlightening and deliciously witty collection of essays on Blackness, faith, pop culture, and the challenges-and rewards-of finding one's way in the world, from a BuzzFeed editor and podcast host.

"A memoir that is immense in its desire to give . . . a rich offering of image, of music, of place."-Hanif Abdurraqib, author of A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance

ONE OF THE MOST ANTICIPATED BOOKS OF 2022-The Millions

At twelve years old, Elamin Abdelmahmoud emigrates with his family from his native Sudan to Kingston, Ontario, arguably one of the most homogenous cities in North America. At the airport, he's handed his Blackness like a passport, and realizes that he needs to learn what this identity means in a new country.

Like all teens, Abdelmahmoud spent his adolescence trying to figure out who he was, but he had to do it while learning to balance a new racial identity and all the false assumptions that came with it. Abdelmahmoud learned to fit in, and eventually became "every liberal white dad's favorite person in the room." But after many years spent trying on different personalities, he now must face the parts of himself he's kept suppressed all this time. He asks, "What happens when those identities stage a jailbreak?"

In his debut collection of essays, Abdelmahmoud gives full voice to each and every one of these conflicting selves. Whether reflecting on how The O.C. taught him about falling in love, why watching wrestling allowed him to reinvent himself, or what it was like being a Muslim teen in the aftermath of 9/11, Abdelmahmoud explores how our experiences and our environments help us in the continuing task of defining who we truly are.

With the perfect balance of relatable humor and intellectual ferocity, Son of Elsewhere confronts what we know about ourselves, and most important, what we're still learning.

"A memoir that is immense in its desire to give . . . a rich offering of image, of music, of place."-Hanif Abdurraqib, author of A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance

ONE OF THE MOST ANTICIPATED BOOKS OF 2022-The Millions

At twelve years old, Elamin Abdelmahmoud emigrates with his family from his native Sudan to Kingston, Ontario, arguably one of the most homogenous cities in North America. At the airport, he's handed his Blackness like a passport, and realizes that he needs to learn what this identity means in a new country.

Like all teens, Abdelmahmoud spent his adolescence trying to figure out who he was, but he had to do it while learning to balance a new racial identity and all the false assumptions that came with it. Abdelmahmoud learned to fit in, and eventually became "every liberal white dad's favorite person in the room." But after many years spent trying on different personalities, he now must face the parts of himself he's kept suppressed all this time. He asks, "What happens when those identities stage a jailbreak?"

In his debut collection of essays, Abdelmahmoud gives full voice to each and every one of these conflicting selves. Whether reflecting on how The O.C. taught him about falling in love, why watching wrestling allowed him to reinvent himself, or what it was like being a Muslim teen in the aftermath of 9/11, Abdelmahmoud explores how our experiences and our environments help us in the continuing task of defining who we truly are.

With the perfect balance of relatable humor and intellectual ferocity, Son of Elsewhere confronts what we know about ourselves, and most important, what we're still learning.

Editorial Reviews

"I remember the day Elamin Abdelmahmoud told me he was writing a book called Son of Elsewhere; just the title broke my heart and somehow still drew me in. Abdelmahmoud is one of our generation's most gifted and emotional writers. He takes us on a fascinating journey of self-discovery, from an awkward adolescent immigrant boy trying to fit in to a courageous young man struggling to carve out an identity of his own without severing his roots. Abdelmahmoud reminds us that, while his story is uniquely his own, we can all learn something about ourselves in ‘The Elsewhere.'"-Brandi Carlile, Grammy Award–winning artist and New York Times bestselling author of Broken Horses

"Son of Elsewhere is a profound, tender collection of stories that speaks to those who exist in and out of liminal spaces. It's a narrative that forces readers to interrogate Blackness beyond American borders, American exceptionalism at the expense of Black and Brown people, and identity between separate languages. Abdelmahmoud is a skillful cartographer of place, architecture, and human emotion, blending them together so effortlessly that one will walk away from this debut seeing the symphony-and collision-in the mundane and the extraordinary. With this book, Abdelmahmoud announces that he is here and we should be so thankful for that."-Morgan Jerkins, New York Times bestselling author of This Will Be My Undoing, Wandering in Strange Lands, and Caul Baby

"It is astounding how accurately and honestly Elamin Abdelmahmoud manages to map the strange territory between cultures that so many migrants call home. The interlinked essays in this collection, which filter the immigrant experience through everything from country music to professional wrestling fan fiction, manage to pull off a rare trick-at once sincere, ironic, hilarious and profound. Son of Elsewhere is the sort of book that can only come from a writer both incisive and open-hearted. Abdelmahmoud, to our great fortune, is both."-Omar El Akkad, Scotiabank Giller Prize–winning author of What ...

"Son of Elsewhere is a profound, tender collection of stories that speaks to those who exist in and out of liminal spaces. It's a narrative that forces readers to interrogate Blackness beyond American borders, American exceptionalism at the expense of Black and Brown people, and identity between separate languages. Abdelmahmoud is a skillful cartographer of place, architecture, and human emotion, blending them together so effortlessly that one will walk away from this debut seeing the symphony-and collision-in the mundane and the extraordinary. With this book, Abdelmahmoud announces that he is here and we should be so thankful for that."-Morgan Jerkins, New York Times bestselling author of This Will Be My Undoing, Wandering in Strange Lands, and Caul Baby

"It is astounding how accurately and honestly Elamin Abdelmahmoud manages to map the strange territory between cultures that so many migrants call home. The interlinked essays in this collection, which filter the immigrant experience through everything from country music to professional wrestling fan fiction, manage to pull off a rare trick-at once sincere, ironic, hilarious and profound. Son of Elsewhere is the sort of book that can only come from a writer both incisive and open-hearted. Abdelmahmoud, to our great fortune, is both."-Omar El Akkad, Scotiabank Giller Prize–winning author of What ...

Short Excerpt Teaser

ONE

Son of Elsewhere

It took two stopovers and nineteen hours of total flying time for me to become Black.

I left Khartoum as a popular and charming (and modest) preteen, and I landed in Canada with two new identities: immigrant, and Black.

When the friendly customs agent stamped my passport and said, "Welcome to Canada," he left out the "also, you're Black now, figure it out" part. In retrospect, it would've been immensely helpful. Having lived twelve years as a not Black person-which is to say, a person entirely unconcerned with his skin colour-you can imagine it was a jarring transition to make.

Without an instruction manual, I was left to my own devices to figure this whole race thing out. And luckily, I had one thing going for me: the place I had just moved to was one of the whitest cities in Canada. This was going to be great.

Let me tell you some of the boring shit that made my eyes glaze over in history class when I was in Sudan. In the early nineteenth century, Muhammad Ali Pasha, an Albanian Ottoman military commander, was sent by the mighty empire to wrestle Egypt from the grip of French occupation under Napoleon. When Muhammad Ali succeeded, he was made Wali, or viceroy, of the Ottoman empire's newly acquired plaything.

Not satisfied with Egypt's resources and gold, the Wali commanded his son to lead troops into Nubia. As it turned out, plundering is mighty easy when you have an advanced army, so the joyride continued. The Ottoman troops rolled on south and seized the province of Kordofan. Where shall we go from here? they wondered. Eh, how about east? Why not! East it was, to take the Sultanate of Sennar, which surrendered without a fight.

Conflict forges identity, though, and the Ottoman audacity managed to unite disparate tribes that had little reason to unite before. Their union was the birth of modern Sudan, though it took its time gestating: in 1881, sixty years after the Ottoman troops invaded, the Mahdist Revolution exploded in Kordofan.

The revolt was named after the Mahdi, an inspiring religious leader who became its rallying point. An army of farmers and merchants and tribesmen, now under a relatively coherent collective identity, said, You know what, enough of this. And Kordofan inspired the other regions to join in the fight.

These regular people, armed with swords and spears and sticks, began a revolution against the occupiers. It concluded in 1883 with victory for the Mahdists, and Sudan became the first (and only) colonized African nation to expel a colonial army by force.

One tiny hiccup: by the time the Mahdists won, Egypt was a de facto protectorate of the British empire. Which meant Sudan had just de facto handed an asskicking to the mightiest army in the world. And empires de facto don't like that very much.

The British took a deep breath, gathered their wits, and in 1899 retook Sudan and demolished the Mahdist state. Then they established a new framework, whereby Britain and Egypt would rule Sudan together.

The population of Kingston, Ontario, is estimated to be about 85 per cent white, which is another way of saying it's like holy shit white. Kingston is so white, way too many people say things like "my Black friend." Kingston is so white (how! white! is it!), it has a town crier who is not only one of its most recognizable faces, he also won a title at the world championship of town criers. Lots of Kingstonians know this fact. They will tell it to you at parties.

All of this is to say: Kingston is not the easiest place to settle as a new immigrant. It's not exactly a gentle introduction to a new land. It's for good reason that most new immigrants to Canada find themselves in a major metropolis-a Toronto or a Montreal or a Vancouver or (if you must) an Edmonton. The idea is, when you have more people who look like you, it's easier to recognize how a place can become home. By contrast, in Kingston the whiteness was overwhelming.

When we arrived in Kingston, Baba made a point of introducing us to the other Sudanese families. All in all, there were eleven families, a small constellation of people who looked like me and could speak like me and were, too, constantly aware that we were far from what we considered home.

I related to the parents better: their Arabic was still instinctive. I could talk to Sudanese parents in K...

Son of Elsewhere

It took two stopovers and nineteen hours of total flying time for me to become Black.

I left Khartoum as a popular and charming (and modest) preteen, and I landed in Canada with two new identities: immigrant, and Black.

When the friendly customs agent stamped my passport and said, "Welcome to Canada," he left out the "also, you're Black now, figure it out" part. In retrospect, it would've been immensely helpful. Having lived twelve years as a not Black person-which is to say, a person entirely unconcerned with his skin colour-you can imagine it was a jarring transition to make.

Without an instruction manual, I was left to my own devices to figure this whole race thing out. And luckily, I had one thing going for me: the place I had just moved to was one of the whitest cities in Canada. This was going to be great.

Let me tell you some of the boring shit that made my eyes glaze over in history class when I was in Sudan. In the early nineteenth century, Muhammad Ali Pasha, an Albanian Ottoman military commander, was sent by the mighty empire to wrestle Egypt from the grip of French occupation under Napoleon. When Muhammad Ali succeeded, he was made Wali, or viceroy, of the Ottoman empire's newly acquired plaything.

Not satisfied with Egypt's resources and gold, the Wali commanded his son to lead troops into Nubia. As it turned out, plundering is mighty easy when you have an advanced army, so the joyride continued. The Ottoman troops rolled on south and seized the province of Kordofan. Where shall we go from here? they wondered. Eh, how about east? Why not! East it was, to take the Sultanate of Sennar, which surrendered without a fight.

Conflict forges identity, though, and the Ottoman audacity managed to unite disparate tribes that had little reason to unite before. Their union was the birth of modern Sudan, though it took its time gestating: in 1881, sixty years after the Ottoman troops invaded, the Mahdist Revolution exploded in Kordofan.

The revolt was named after the Mahdi, an inspiring religious leader who became its rallying point. An army of farmers and merchants and tribesmen, now under a relatively coherent collective identity, said, You know what, enough of this. And Kordofan inspired the other regions to join in the fight.

These regular people, armed with swords and spears and sticks, began a revolution against the occupiers. It concluded in 1883 with victory for the Mahdists, and Sudan became the first (and only) colonized African nation to expel a colonial army by force.

One tiny hiccup: by the time the Mahdists won, Egypt was a de facto protectorate of the British empire. Which meant Sudan had just de facto handed an asskicking to the mightiest army in the world. And empires de facto don't like that very much.

The British took a deep breath, gathered their wits, and in 1899 retook Sudan and demolished the Mahdist state. Then they established a new framework, whereby Britain and Egypt would rule Sudan together.

The population of Kingston, Ontario, is estimated to be about 85 per cent white, which is another way of saying it's like holy shit white. Kingston is so white, way too many people say things like "my Black friend." Kingston is so white (how! white! is it!), it has a town crier who is not only one of its most recognizable faces, he also won a title at the world championship of town criers. Lots of Kingstonians know this fact. They will tell it to you at parties.

All of this is to say: Kingston is not the easiest place to settle as a new immigrant. It's not exactly a gentle introduction to a new land. It's for good reason that most new immigrants to Canada find themselves in a major metropolis-a Toronto or a Montreal or a Vancouver or (if you must) an Edmonton. The idea is, when you have more people who look like you, it's easier to recognize how a place can become home. By contrast, in Kingston the whiteness was overwhelming.

When we arrived in Kingston, Baba made a point of introducing us to the other Sudanese families. All in all, there were eleven families, a small constellation of people who looked like me and could speak like me and were, too, constantly aware that we were far from what we considered home.

I related to the parents better: their Arabic was still instinctive. I could talk to Sudanese parents in K...