Genre Fiction

- Publisher : Modern Library

- Published : 13 Sep 2022

- Pages : 704

- ISBN-10 : 0679643567

- ISBN-13 : 9780679643562

- Language : English

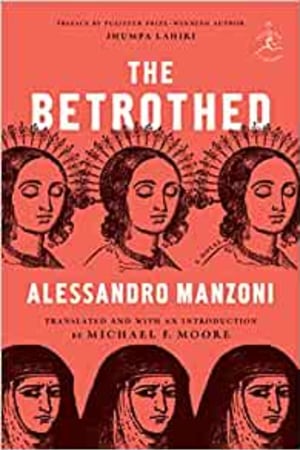

The Betrothed: A Novel

The timeless masterpiece from Alessandro Manzoni, the father of modern Italian literature, in the first new English-language translation in fifty years, hailed as "a landmark literary occasion" by Jhumpa Lahiri in her preface to the edition

The Betrothed is a cornerstone of Italian culture, language, and literature. Published in its final form in 1842, the novel has inspired generations of Italian readers and writers. Giuseppe Verdi composed his majestic Requiem Mass in honor of Manzoni. Italo Calvino called the novel "a classic that has never ceased shaping reality in Italy" while Umberto Eco praised its author as a "most subtle critic and analyst of languages." The Betrothed has been celebrated by Primo Levi and Natalia Ginzburg, and is one of Pope Francis's favorite books. But, until now, it has remained relatively unknown to English readers.

In the fall of 1628, two young lovers are forced to flee their village on the shores of Lake Como after a powerful lord prevents their marriage, plunging them into the maelstrom of history. Manzoni draws on actual people and events to create an unforgettable fresco of Italian life and society. In this greatest of historical novels, he takes the reader on a journey through the Spanish occupation of Milan, the ravages of war, class tensions, social injustice, religious faith, and a plague that devastates northern Italy. But within Manzoni's epic tale, readers will also hear powerful echoes of our own day.

Michael F. Moore's dynamic new translation brings to life Manzoni's timeless literary masterpiece.

The Betrothed is a cornerstone of Italian culture, language, and literature. Published in its final form in 1842, the novel has inspired generations of Italian readers and writers. Giuseppe Verdi composed his majestic Requiem Mass in honor of Manzoni. Italo Calvino called the novel "a classic that has never ceased shaping reality in Italy" while Umberto Eco praised its author as a "most subtle critic and analyst of languages." The Betrothed has been celebrated by Primo Levi and Natalia Ginzburg, and is one of Pope Francis's favorite books. But, until now, it has remained relatively unknown to English readers.

In the fall of 1628, two young lovers are forced to flee their village on the shores of Lake Como after a powerful lord prevents their marriage, plunging them into the maelstrom of history. Manzoni draws on actual people and events to create an unforgettable fresco of Italian life and society. In this greatest of historical novels, he takes the reader on a journey through the Spanish occupation of Milan, the ravages of war, class tensions, social injustice, religious faith, and a plague that devastates northern Italy. But within Manzoni's epic tale, readers will also hear powerful echoes of our own day.

Michael F. Moore's dynamic new translation brings to life Manzoni's timeless literary masterpiece.

Short Excerpt Teaser

Chapter 1

The branch of Lake Como that turns south between two unbroken mountain chains, bordered by coves and inlets that echo the furrowed slopes, suddenly narrows to take the flow and shape of a river, between a promontory on the right and a wide shoreline on the opposite side. The bridge that joins the two sides at this point seems to make this transformation even more visible to the eye and mark the spot where the lake ends and the Adda begins again, to reclaim the name lake where the shores, newly distant, allow the water to spread and slowly pool into fresh inlets and coves. Formed from the sediment of three large streams, the shoreline lies at the foot of two neighboring mountains, the first called San Martino, the second, in Lombard dialect, the "Resegone"-the big saw-after the row of many small peaks that really do make it look like one. So clear is the resemblance that no one-provided they are directly facing it, from the northern walls of Milan, for example-could fail to immediately distinguish this summit from other mountains in that long and vast range with more obscure names and more common shapes. For a good stretch the shore rises upward into a smooth rolling slope. Then it breaks off into small hills and ravines, steep inclines and flat terraces, molded by the contours of the two mountains and the erosion of the waters. The water's edge, cut by the outlets of the streams, is almost all pebbles and stones. The rest is fields and vineyards, dotted with towns, villages, and hamlets. Here and there a woods climbs up the side of the mountain.

Lecco, the capital that lends its name to the province, stands at a short remove from the bridge, and is on and indeed partly inside the lake when the water rises. Nowadays it is a large town well on its way to becoming a city. At the time of the events I am about to relate, this already good-sized village was also fortified, which conferred upon it the honor of a commander in residence, and the benefit of a permanent garrison of Spanish soldiers, who taught modesty to the girls and women of the town, gave an occasional tap on the back to a husband or father, and, at summer's end, never failed to spread out into the vineyards to thin the grapes and relieve the peasants of the trouble of harvesting them.

Roads and footpaths used to run-and still do-from town to town, from summit to shore, from hill to hill. Some are more or less steep; some are level. In places they dip, sinking between two walls, and all you can see when you look up is a patch of sky and a mountaintop. In others they climb to open embankments, where the view encompasses a broader panorama, always rich, always new, depending on the vantage point and how much of the vast expanse can be seen, and on whether the landscape protrudes or recedes, stands out from or disappears into the horizon.

One piece, then another, then a long stretch of that vast and varied mirror of water. Over here, the lake-terminating at the far end or vanishing into a cluster, a procession of mountains-slowly growing wider between yet more mountains that unfold before the eyes, one by one, whose image, alongside that of the towns by the lake, is reflected upside down in the water. Over there, a bend in the river, then more lake, then river again disappearing into a shiny ribbon curling between the mountains on either side, and slowly descending to vanish on the horizon.

The place from which you contemplate these varied sights offers its own display on every side. The mountain along whose slopes you walk unfolds its peaks and crags above and around you, distinct, prominent, changing with every step, opening and then circling into ridges where a lone summit had at first appeared. The shapes that were reflected in the lake only minutes before now appear close to the summit. The tame, pleasant foothills temper the wild landscape and enhance the magnificence of the other vistas.

Along one of these footpaths, on the evening of the seventh day of November in 1628, Don Abbondio, the parish priest of one of the villages just mentioned, was making his way home from a leisurely walk. (Neither here nor elsewhere does the manuscript give the name of his parish or family.) He was calmly reciting the Liturgy of the Hours. Occasionally, between one psalm and another, he would close his breviary, keeping his right index finger inside as a bookmark. Clasping his hands together behind his back, he would continue his walk, staring at the ground and kicking toward the wall any stones that got in the way. Then he would look up, let his eyes wander idly, and gaze at the wide and uneven splashes of purple on the cliffs, painted there by the light of the se...

The branch of Lake Como that turns south between two unbroken mountain chains, bordered by coves and inlets that echo the furrowed slopes, suddenly narrows to take the flow and shape of a river, between a promontory on the right and a wide shoreline on the opposite side. The bridge that joins the two sides at this point seems to make this transformation even more visible to the eye and mark the spot where the lake ends and the Adda begins again, to reclaim the name lake where the shores, newly distant, allow the water to spread and slowly pool into fresh inlets and coves. Formed from the sediment of three large streams, the shoreline lies at the foot of two neighboring mountains, the first called San Martino, the second, in Lombard dialect, the "Resegone"-the big saw-after the row of many small peaks that really do make it look like one. So clear is the resemblance that no one-provided they are directly facing it, from the northern walls of Milan, for example-could fail to immediately distinguish this summit from other mountains in that long and vast range with more obscure names and more common shapes. For a good stretch the shore rises upward into a smooth rolling slope. Then it breaks off into small hills and ravines, steep inclines and flat terraces, molded by the contours of the two mountains and the erosion of the waters. The water's edge, cut by the outlets of the streams, is almost all pebbles and stones. The rest is fields and vineyards, dotted with towns, villages, and hamlets. Here and there a woods climbs up the side of the mountain.

Lecco, the capital that lends its name to the province, stands at a short remove from the bridge, and is on and indeed partly inside the lake when the water rises. Nowadays it is a large town well on its way to becoming a city. At the time of the events I am about to relate, this already good-sized village was also fortified, which conferred upon it the honor of a commander in residence, and the benefit of a permanent garrison of Spanish soldiers, who taught modesty to the girls and women of the town, gave an occasional tap on the back to a husband or father, and, at summer's end, never failed to spread out into the vineyards to thin the grapes and relieve the peasants of the trouble of harvesting them.

Roads and footpaths used to run-and still do-from town to town, from summit to shore, from hill to hill. Some are more or less steep; some are level. In places they dip, sinking between two walls, and all you can see when you look up is a patch of sky and a mountaintop. In others they climb to open embankments, where the view encompasses a broader panorama, always rich, always new, depending on the vantage point and how much of the vast expanse can be seen, and on whether the landscape protrudes or recedes, stands out from or disappears into the horizon.

One piece, then another, then a long stretch of that vast and varied mirror of water. Over here, the lake-terminating at the far end or vanishing into a cluster, a procession of mountains-slowly growing wider between yet more mountains that unfold before the eyes, one by one, whose image, alongside that of the towns by the lake, is reflected upside down in the water. Over there, a bend in the river, then more lake, then river again disappearing into a shiny ribbon curling between the mountains on either side, and slowly descending to vanish on the horizon.

The place from which you contemplate these varied sights offers its own display on every side. The mountain along whose slopes you walk unfolds its peaks and crags above and around you, distinct, prominent, changing with every step, opening and then circling into ridges where a lone summit had at first appeared. The shapes that were reflected in the lake only minutes before now appear close to the summit. The tame, pleasant foothills temper the wild landscape and enhance the magnificence of the other vistas.

Along one of these footpaths, on the evening of the seventh day of November in 1628, Don Abbondio, the parish priest of one of the villages just mentioned, was making his way home from a leisurely walk. (Neither here nor elsewhere does the manuscript give the name of his parish or family.) He was calmly reciting the Liturgy of the Hours. Occasionally, between one psalm and another, he would close his breviary, keeping his right index finger inside as a bookmark. Clasping his hands together behind his back, he would continue his walk, staring at the ground and kicking toward the wall any stones that got in the way. Then he would look up, let his eyes wander idly, and gaze at the wide and uneven splashes of purple on the cliffs, painted there by the light of the se...