Literature & Fiction

- Publisher : Ballantine Books; Reissue edition

- Published : 08 Sep 1997

- Pages : 408

- ISBN-10 : 0449912558

- ISBN-13 : 9780449912553

- Language : English

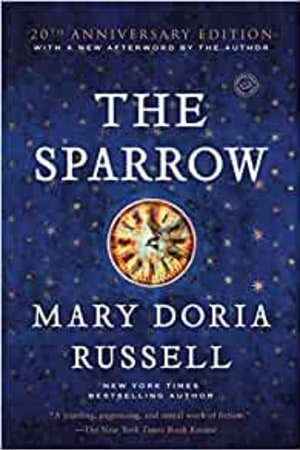

The Sparrow: A Novel (The Sparrow Series)

A visionary work that combines speculative fiction with deep philosophical inquiry, The Sparrow tells the story of a charismatic Jesuit priest and linguist, Emilio Sandoz, who leads a scientific mission entrusted with a profound task: to make first contact with intelligent extraterrestrial life. The mission begins in faith, hope, and beauty, but a series of small misunderstandings brings it to a catastrophic end.

Praise for The Sparrow

"A startling, engrossing, and moral work of fiction."-The New York Times Book Review

"Important novels leave deep cracks in our beliefs, our prejudices, and our blinders. The Sparrow is one of them."-Entertainment Weekly

"Powerful . . . The Sparrow tackles a difficult subject with grace and intelligence."-San Francisco Chronicle

"Provocative, challenging . . . recalls both Arthur C. Clarke and H. G. Wells, with a dash of Ray Bradbury for good measure."-The Dallas Morning News

"[Mary Doria] Russell shows herself to be a skillful storyteller who subtly and expertly builds suspense."-USA Today

Praise for The Sparrow

"A startling, engrossing, and moral work of fiction."-The New York Times Book Review

"Important novels leave deep cracks in our beliefs, our prejudices, and our blinders. The Sparrow is one of them."-Entertainment Weekly

"Powerful . . . The Sparrow tackles a difficult subject with grace and intelligence."-San Francisco Chronicle

"Provocative, challenging . . . recalls both Arthur C. Clarke and H. G. Wells, with a dash of Ray Bradbury for good measure."-The Dallas Morning News

"[Mary Doria] Russell shows herself to be a skillful storyteller who subtly and expertly builds suspense."-USA Today

Editorial Reviews

"A startling, engrossing, and moral work of fiction."-The New York Times Book Review

"Important novels leave deep cracks in our beliefs, our prejudices, and our blinders. The Sparrow is one of them."-Entertainment Weekly

"Powerful . . . The Sparrow tackles a difficult subject with grace and intelligence."-San Francisco Chronicle

"Provocative, challenging . . . recalls both Arthur C. Clarke and H. G. Wells, with a dash of Ray Bradbury for good measure."-The Dallas Morning News

"[Mary Doria] Russell shows herself to be a skillful storyteller who subtly and expertly builds suspense."-USA Today

"Important novels leave deep cracks in our beliefs, our prejudices, and our blinders. The Sparrow is one of them."-Entertainment Weekly

"Powerful . . . The Sparrow tackles a difficult subject with grace and intelligence."-San Francisco Chronicle

"Provocative, challenging . . . recalls both Arthur C. Clarke and H. G. Wells, with a dash of Ray Bradbury for good measure."-The Dallas Morning News

"[Mary Doria] Russell shows herself to be a skillful storyteller who subtly and expertly builds suspense."-USA Today

Readers Top Reviews

Sean McQuilkenDoroth

Well written with a believable, likeable characters, who develop during the story. I like the way to book has two time lines, one chapter on the expedition, the next the aftermath etc., and how one lead to the other was progressively revealed. The downside to this is that you know from the start that all the expedition members bar one die. There are religious aspects to the book, the main theme I suppose is why bad stuff happens to good people if there is a benevolent omnipotent god. I was disappointed that the book did not explain this , (only kidding!). It is nice though that for once religious people aren't portrayed as being idiots or as the bad guys. It is not a "hard" sci-fi book. There is not details for example on how their asteroid spacecraft could be accelerated to near light speed etc. Also landing immediately on the alien planet, the first humans have travelled to, seems very risky. They could have all dies from disease or worst wiped out the alien civilisation.

𓅃𓋴𓌬 𓅱 𓈃

This is a good book, not great. For me much of the 'chumminess' was a little nauseating, but I suppose it gave the characters some back story (something my wife hates). Definitely not like Stanislaw Lem. Ignoring the qualities of the book, which have been detailed scrupulously in other reviews, I just wanted to highlight the message I picked up very loud and clear. That message is echoed across the world of sci-fi, although the message is often diluted by the 'fun' of violence (such as 'Independence Day'), etc. In many ways this issues the same sort of warnings given out by the aforementioned Lem in wonderful books such as 'Solaris' (not as good as the Tarkovsky magnum opus however) and 'The Invincible'. We should stop our puny search for life 'out there', because when we find it it will be so alien that we cannot hope to understand it and any belief that we can will simply be a conceit. How could we possible understand an alien life-form any more than we can understand the workings of the universe? The word 'alien' is a clue in itself. In 'Solaris' it is very clear just how alien the alien is - after all, a sentient ocean is not the sort of alien that you could easily hang around with and trade with. However, 'The Sparrow' illustrates the danger of our conceit that we can understand something that looks vaguely similar to us and would appear, on the surface, to have understandable social structures. Clearly the humans were wrong on almost every level. As Lem noted in 'Solaris', 'We don't need other worlds. We need a mirror'. Exactly right, and films like 'Star Wars, et al, bear this out. We don't really want to meet something like the Solarian ocean, we want to meet a nice humanoid alien that we can have a bit of banter with and make ourselves feel better about our own somewhat isolated (in terms of the universe) situation. SETI should end now. Be careful what you wish for, as Kelvin, Snaut, Gibarian and Sartorius will tell you.

Angular Squaremadmar

Abandoned and deleted at 70%. Awful smug characters who seem to sit about laughing hysterically at their own jokes. Ludicrous premise of Catholics in space. The dullest and most unfeasible aliens Very slim plot with lots of jumping about in time. Very limp character- driven sci-fi/ Religious propaganda. Like some self published Kindle Unlimited rubbish.

bookgal

Like at least two others who have read and reviewed this book, I purchased it because I had read something else by Mary Doria Russell and had enjoyed it very much. Then I realized that it had been categorized as science fiction. I don't have a problem with science fiction but I also don't read it often and for some reason I hesitated to begin reading this. Still I eventually reached a point where I reached for it, determined to find out why this author wrote this form of story, when I had so enjoyed a WESTERN by her. And it pretty quickly became evident. It is a book on the future with its very beginnings apropos of today (and the early part of the book does indeed begin almost this year — what a shock!). Simply and most obviously, this is a book about the human spirit and the search that all of us seem to go through for a sense of place, of worth and meaning. So much more than I ever envisioned when I bought the book or began the book. The story kicks off in the year 2059 with a Jesuit priest who has been 'rescued' from a mission to the planet Rakhat. Remember that this is indeed the beginning of the book and as a plot will finish the story, but it really begins with a group of disparate people who slowly come together: the Jesuit Emilio Sandoz who has spent his career in the Society of Jesus, traveling the world as a linguist but never staying for very long until he returns to the place where he grew up, the small village of La Perla in Puerto Rico. It is there that he meets the others: A retired engineer and his physician wife; a technician working at a listening station seeking transmissions from other worlds and Sofia Mendez, an artificial intelligence specialist. They form strong bonds and relationships with each other and it is those ties that bind when the technician hears singing from a distant planet. He shares the discovery with his friends but it most strongly resonates with Sandoz, who has struggled with his faith but sees the songs as a sign that it is God's will that this group of people not only have come together for this moment but that it is for them to travel to the planet and learn about the creators of the songs. Needless to say, the book is told in flashbacks, the report that made it back to Earth and from Sandoz himself, who is the sole survivor of the trip, as a broken man barely holding together mentally, as well as physically. And it is to him to make sense of the trip and the experiences he faced. This is the main focus and what sets this book far from being just — if you can say that without demeaning the genre — science fiction. For ultimately this is a story about a man who in one of the characters words came very close to God, who felt the rapture of belief and then has his faith perhaps irreparably shattered by what happens during the trip he once thought was planned by God. <br...

Jason Galbraith

At over 500 pages counting the Afterword and appendices, "The Sparrow" is too thick for me to find room for it on my shelves, so I am sending it to a beloved (and celibate) ex-girlfriend who years ago sent me Martin Scorsese's passion project "Silence," about Jesuits in Japan in the seventeenth century. I couldn't think of a person who would more want to read a story about the first Jesuits to go to Alpha Centauri. The aliens on a planet orbiting the smallest of the three suns that make up the Centauri system are very different from those in "The Three-Body Problem," another very popular novel in which it turns out there is intelligent life there. They are just beginning to see what radio can be used for and one of the first transmissions of their music is picked up by an astronomer at the Arecibio Radio Telescope in Puerto Rico. One of the first people he tells that he has picked up an extraterrestrial signal is the hero of the book, Jesuit priest Emilio Sandoz, who has recently returned home to the island after years of short-term missions to deprived people all over Earth. He immediately recruits the astronomer, his three other closest friends, and three other Jesuits to travel to the planet, named Rakhat by its inhabitants, in a hollowed-out asteroid at an average of 25% of c. Mary Doria Russell's only mistake with this book was setting it within her own lifetime (it starts in the mid-2010s). It will probably be the 2110s before we have Australians on Mars and miners throughout the asteroid belt (assuming we can avoid a Third World War or comprehensive environmental collapse). The book ends in 2060, when as one character observes the population of Earth is nearly 16 billion (which isn't going to happen by then, or probably ever). Even in the 2010s the technological singularity is approaching; you pretty much need to have a Ph.D. to have a job. Most other jobs are being handed over to AIs taught by the last humans to do those jobs and set up by indentured servants like Sofia Mendes, the second-most compelling character in the book. I caught myself doing something that these days, I only do for the best novels: casting the movie version in my head. The thing is, like "Dune," this book is too sprawling to be told with a single two- or even three-hour movie. It is divided into 3 acts, each of which should be its own movie. The first act is Sandoz's life and friendships on Earth and on the (from their perspective brief) journey inside the asteroid to Rakhat. The second act is Rakhat itself. These two acts are told in flashback through the memory of Sandoz, who in the third act is the only human who makes it back alive (though horribly maimed) to Earth. The first movie could be named "Scientists," the second could be "Missionaries" and the third could only be "Priests" since literally everyone Sandoz interacts with...

Short Excerpt Teaser

Ballantine Reader's Circle: The Sparrow (Excerpt)

Chapter 1

ROME: DECEMBER 2059

On December 7, 2059, Emilio Sandoz was released from the isolation ward of Salvator Mundi Hospital in the middle of the night and transported in a bread van to the Jesuit Residence at Number 5 Borgo Santo Spìrito, a few minutes' walk across St. Peter's Square from the Vatican. The next day, ignoring shouted questions and howls of journalistic outrage as he read, a Jesuit spokesman issued a short statement to the frustrated and angry media mob that had gathered outside Number 5's massive front door.

"To the best of our knowledge, Father Emilio Sandoz is the sole survivor of the Jesuit mission to Rakhat. Once again, we extend our thanks to the U.N., to the Contact Consortium and to the Asteroid Mining Division of Ohbayashi Corporation for making the return of Father Sandoz possible. We have no additional information regarding the fate of the Contact Consortium's crew members; they are in our prayers. Father Sandoz is too ill to question at this time and his recovery is expected to take months. Until then, there can be no further comment on the Jesuit mission or on the Contact Consortium's allegations regarding Father Sandoz's conduct on Rakhat."

This was simply to buy time.

It was true, of course, that Sandoz was ill. The man's whole body was bruised by the blooms of spontaneous hemorrhages where tiny blood vessel walls had breached and spilled their contents under his skin. His gums had stopped bleeding, but it would be a long while before he could eat normally. Eventually, something would have to be done about his hands.

Now, however, the combined effects of scurvy, anemia and exhaustion kept him asleep twenty hours out of the day. When awake, he lay motionless, coiled like a fetus and almost as helpless.

The door to his small room was nearly always left open in those early weeks. One afternoon, thinking to prevent Father Sandoz from being disturbed while the hallway floor was polished, Brother Edward Behr closed it, despite warnings about this from the Salvator Mundi staff. Sandoz happened to wake up and found himself shut in. Brother Edward did not repeat the mistake.

Vincenzo Giuliani, the Father General of the Society of Jesus, went each morning to look in on the man. He had no idea if Sandoz was aware of being observed; it was a familiar feeling. When very young, when the Father General was just plain Vince Giuliani, he had been fascinated by Emilio Sandoz, who was a year ahead of Giuliani during the decade-long process of priestly formation. A strange boy, Sandoz. A puzzling man. Vincenzo Giuliani had made a statesman's career of understanding other men, but he had never understood this one.

Gazing at Emilio, sick now and almost mute, Giuliani knew that Sandoz was unlikely to give up his secrets any time soon. This did not distress him. Vincenzo Giuliani was a patient man. One had to be patient to thrive in Rome, where time is measured not in centuries but in millennia, where patience and the long view have always distinguished political life. The city gave its name to the power of patience--Romanità. Romanità excludes emotion, hurry, doubt. Romanità waits, sees the moment and moves ruthlessly when the time is right. Romanità rests on an absolute conviction of ultimate success and arises from a single principle, Cunctando regitur mundis: Waiting, one conquers all.

So, even after sixty years, Vincenzo Giuliani felt no sense of impatience with his inability to understand Emilio Sandoz, only a sense of how satisfying it would be when the wait paid off.

The Father General's private secretary contacted Father John Candotti on the Feast of the Holy Innocents, three weeks after Emilio's arrival at Number 5. "Sandoz is well enough to see you now," Johannes Voelker informed Candotti. "Be here by two."

Be here by two! John thought irritably, marching along toward Vatican City from the retreat house where he'd just been assigned a stuffy little room with a view of Roman walls--the stone only inches from his pointless window. Candotti had dealt with Voelker a couple of times since arriving and had taken a dislike to the Austrian from the start. In fact, John Candotti disliked everything about his present situation.

For one thing, he didn't understand why he'd been brought into this business. Neither a lawyer nor an academic, John Candotti was content to have come out on the less prestigious end of the Jesuit dictum, Publish or parish, and he was hip-deep in preparations for the grammar school Christmas program when his superior contacted him and told him to fly to Rome at the end of the week. "The ...

Chapter 1

ROME: DECEMBER 2059

On December 7, 2059, Emilio Sandoz was released from the isolation ward of Salvator Mundi Hospital in the middle of the night and transported in a bread van to the Jesuit Residence at Number 5 Borgo Santo Spìrito, a few minutes' walk across St. Peter's Square from the Vatican. The next day, ignoring shouted questions and howls of journalistic outrage as he read, a Jesuit spokesman issued a short statement to the frustrated and angry media mob that had gathered outside Number 5's massive front door.

"To the best of our knowledge, Father Emilio Sandoz is the sole survivor of the Jesuit mission to Rakhat. Once again, we extend our thanks to the U.N., to the Contact Consortium and to the Asteroid Mining Division of Ohbayashi Corporation for making the return of Father Sandoz possible. We have no additional information regarding the fate of the Contact Consortium's crew members; they are in our prayers. Father Sandoz is too ill to question at this time and his recovery is expected to take months. Until then, there can be no further comment on the Jesuit mission or on the Contact Consortium's allegations regarding Father Sandoz's conduct on Rakhat."

This was simply to buy time.

It was true, of course, that Sandoz was ill. The man's whole body was bruised by the blooms of spontaneous hemorrhages where tiny blood vessel walls had breached and spilled their contents under his skin. His gums had stopped bleeding, but it would be a long while before he could eat normally. Eventually, something would have to be done about his hands.

Now, however, the combined effects of scurvy, anemia and exhaustion kept him asleep twenty hours out of the day. When awake, he lay motionless, coiled like a fetus and almost as helpless.

The door to his small room was nearly always left open in those early weeks. One afternoon, thinking to prevent Father Sandoz from being disturbed while the hallway floor was polished, Brother Edward Behr closed it, despite warnings about this from the Salvator Mundi staff. Sandoz happened to wake up and found himself shut in. Brother Edward did not repeat the mistake.

Vincenzo Giuliani, the Father General of the Society of Jesus, went each morning to look in on the man. He had no idea if Sandoz was aware of being observed; it was a familiar feeling. When very young, when the Father General was just plain Vince Giuliani, he had been fascinated by Emilio Sandoz, who was a year ahead of Giuliani during the decade-long process of priestly formation. A strange boy, Sandoz. A puzzling man. Vincenzo Giuliani had made a statesman's career of understanding other men, but he had never understood this one.

Gazing at Emilio, sick now and almost mute, Giuliani knew that Sandoz was unlikely to give up his secrets any time soon. This did not distress him. Vincenzo Giuliani was a patient man. One had to be patient to thrive in Rome, where time is measured not in centuries but in millennia, where patience and the long view have always distinguished political life. The city gave its name to the power of patience--Romanità. Romanità excludes emotion, hurry, doubt. Romanità waits, sees the moment and moves ruthlessly when the time is right. Romanità rests on an absolute conviction of ultimate success and arises from a single principle, Cunctando regitur mundis: Waiting, one conquers all.

So, even after sixty years, Vincenzo Giuliani felt no sense of impatience with his inability to understand Emilio Sandoz, only a sense of how satisfying it would be when the wait paid off.

The Father General's private secretary contacted Father John Candotti on the Feast of the Holy Innocents, three weeks after Emilio's arrival at Number 5. "Sandoz is well enough to see you now," Johannes Voelker informed Candotti. "Be here by two."

Be here by two! John thought irritably, marching along toward Vatican City from the retreat house where he'd just been assigned a stuffy little room with a view of Roman walls--the stone only inches from his pointless window. Candotti had dealt with Voelker a couple of times since arriving and had taken a dislike to the Austrian from the start. In fact, John Candotti disliked everything about his present situation.

For one thing, he didn't understand why he'd been brought into this business. Neither a lawyer nor an academic, John Candotti was content to have come out on the less prestigious end of the Jesuit dictum, Publish or parish, and he was hip-deep in preparations for the grammar school Christmas program when his superior contacted him and told him to fly to Rome at the end of the week. "The ...