Sociology

- Publisher : Random House Trade Paperbacks; Reprint edition

- Published : 25 Jan 2022

- Pages : 256

- ISBN-10 : 0593243633

- ISBN-13 : 9780593243633

- Language : English

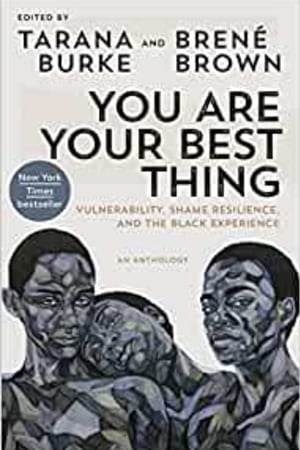

You Are Your Best Thing: Vulnerability, Shame Resilience, and the Black Experience

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • Tarana Burke and Dr. Brené Brown bring together a dynamic group of Black writers, organizers, artists, academics, and cultural figures to discuss the topics the two have dedicated their lives to understanding and teaching: vulnerability and shame resilience.

Contributions by Kiese Laymon, Imani Perry, Laverne Cox, Jason Reynolds, Austin Channing Brown, and more

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY MARIE CLAIRE AND BOOKRIOT

It started as a text between two friends.

Tarana Burke, founder of the ‘me too.' Movement, texted researcher and writer Brené Brown to see if she was free to jump on a call. Brené assumed that Tarana wanted to talk about wallpaper. They had been trading home decorating inspiration boards in their last text conversation so Brené started scrolling to find her latest Pinterest pictures when the phone rang.

But it was immediately clear to Brené that the conversation wasn't going to be about wallpaper. Tarana's hello was serious and she hesitated for a bit before saying, "Brené, you know your work affected me so deeply, but as a Black woman, I've sometimes had to feel like I have to contort myself to fit into some of your words. The core of it rings so true for me, but the application has been harder."

Brené replied, "I'm so glad we're talking about this. It makes sense to me. Especially in terms of vulnerability. How do you take the armor off in a country where you're not physically or emotionally safe?"

Long pause.

"That's why I'm calling," said Tarana. "What do you think about working together on a book about the Black experience with vulnerability and shame resilience?"

There was no hesitation.

Burke and Brown are the perfect pair to usher in this stark, potent collection of essays on Black shame and healing. Along with the anthology contributors, they create a space to recognize and process the trauma of white supremacy, a space to be vulnerable and affirm the fullness of Black love and Black life.

Contributions by Kiese Laymon, Imani Perry, Laverne Cox, Jason Reynolds, Austin Channing Brown, and more

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY MARIE CLAIRE AND BOOKRIOT

It started as a text between two friends.

Tarana Burke, founder of the ‘me too.' Movement, texted researcher and writer Brené Brown to see if she was free to jump on a call. Brené assumed that Tarana wanted to talk about wallpaper. They had been trading home decorating inspiration boards in their last text conversation so Brené started scrolling to find her latest Pinterest pictures when the phone rang.

But it was immediately clear to Brené that the conversation wasn't going to be about wallpaper. Tarana's hello was serious and she hesitated for a bit before saying, "Brené, you know your work affected me so deeply, but as a Black woman, I've sometimes had to feel like I have to contort myself to fit into some of your words. The core of it rings so true for me, but the application has been harder."

Brené replied, "I'm so glad we're talking about this. It makes sense to me. Especially in terms of vulnerability. How do you take the armor off in a country where you're not physically or emotionally safe?"

Long pause.

"That's why I'm calling," said Tarana. "What do you think about working together on a book about the Black experience with vulnerability and shame resilience?"

There was no hesitation.

Burke and Brown are the perfect pair to usher in this stark, potent collection of essays on Black shame and healing. Along with the anthology contributors, they create a space to recognize and process the trauma of white supremacy, a space to be vulnerable and affirm the fullness of Black love and Black life.

Readers Top Reviews

techgirlKatina Horto

Oh my. This was not what I was expecting but so what I needed. The essays written in this book are written from places of vulnerability, strength, courage, and transparency. Wow. Highly recommend!

Misty C

Such an amazing Anthology edited by two powerful and empowering women, showing us that, once again, the lived experiences of Black women & men will lay the foundation for healing for all of us. Shame is at the root of so much of our suffering and while sitting in it feels impossibly hard, these narratives show us how to do it. Thank you for knocking me on my ass to get down to the next layer of healing and work to dismantle oppressive systems in this country and the world (and for an introduction to the discussion of respectability politics- shout out to Tanya Denise Fields for that!).

Tasnim McCormick Ben

Generous truth-telling, beauty - compelling relevance. Don't miss this one. A very important read for all of us - now - and as we move forward. A gift of a book, a rare gift.

Kindle

This book is an important compliment to Brene Browns work. Black vulnerability is different from white vulnerability and deserves to be a unique focus. The essays were good and it would be good to have a scholar!y discussion about the issue too.

GigiMystic Elf

I am a HUGE fan of Brene Brown and a Black woman, so when I heard about this book, I was thrilled. I did not read the description carefully. This book is a collection of essays. It is not typical of Brene Brown's work. I hoped for research about the experience of Black people. I hoped for Brene Brown's sharp attention to the data accompanied by her ability to narrow to the marrow. Instead I got essays. The essays described painful personal experiences and I commend each and every contributor for sharing his/her/their story. Thank you. It was crazy brave. It just wasn't the work I expected from Brene Brown. It felt hollow and like a commercial expoit instead of a genuine, hard earned, data driven effort. I can't imagine the effort it takes to create the revolutionary and absorbing books that Brene Brown has produced. Still I hope one day she will honor people of color with a book of the same caliber as her others. It would be such a gift.

Short Excerpt Teaser

Introduction: A Conversation

Brené Brown: We could start the story of this book when you texted me to ask if we could talk, and I thought you wanted to continue our ongoing conversation about wallpaper and landscaping-but what came before that? When did the idea for this book come to you?

Tarana Burke: It was after we did SharetheMic on social media, in the summer of 2020. There had been this intense public unrest happening in the country after George Floyd and Breonna Taylor were murdered. In private, I was having these really heartfelt conversations with Black folks who were just struggling: I can't watch any more of this. I can't take this anymore. I cannot . . . And in public, the conversation was, How can we get white people to be better? How can we get white people to be antiracist? Antiracism became the order of the day. But there was no focus on Black humanity. I kept thinking, Where's the space for us to talk about what this does to us, how this affects our lives? And so I was thinking to myself that I really wanted to have a conversation with you.

At first, I struggled to text you. I kept asking myself, Why am I hesitating to reach out to her? We have a close enough friendship to talk about anything. Your work is so important to me and my experience as a human being, but as a Black woman, I often felt like I had to contort myself to fit into the work and see myself in it. I wanted to talk to you about adding to it: "What is the Black experience with shame resilience?" Because white supremacy has added another layer to the kind of shame we have to deal with, and the kind of resilience we have to build, and the kind of vulnerability that we are constantly subjected to whether we choose it or not.

So, yeah, I called and said all of that-but I was not as eloquent [laughter] at the time. I will never forget that phone call. I texted, Can we talk? and you texted back, Sure. Once we got on the phone and I shared the idea, the first thing you said was "Oh, hell yeah. Oh, absolutely! Yes, I want to talk about that. Yes, I want to do this." At that point I was just thinking, Oh, and here I was worrying about offending you and wanting to have a real conversation. So, that was the beginning from my side. What was happening on your side?

Brené: From my side, well, admittedly, I'd probably do anything you ask me to do. But the timing was bigger than us. I had really been grappling over the last couple of years with trying to figure out how to be more inclusive-how to present the work in a way that invited more people to see themselves. The last thing I ever wanted to do was put work in the world around shame, vulnerability, and courage, then make people feel like they had to do something extra to find themselves in it. I thought I had controlled for that with my sample, because I've always been hypervigilant about diversity in the people I interview and in data sources. In fact, one of the early criticisms of my work was that the sample population actually overindexed around Black women and Latinx folks. But I started to get comments, especially from Black women and men: "I had to work at it more to see myself in it than I would have preferred or I would have liked to or than I even should have had to." Finally, it was the combination of a conversation with you and a conversation with Austin Channing Brown on her TV show, where I thought, The problem isn't the research. The research resonates with a diverse group of people because it's based on a diverse sample. But the way I present my research to the world does not always resonate because I often use myself and my stories as examples, and I have a very privileged white experience. That was the huge aha for me.

Tarana: Yeah, that makes sense.

Brené: One of the things that struck me was, in The Gifts of Imperfection, there's a scene where I'm in sweats and have dirty hair and I'm running up the Nordstrom escalator with my daughter to exchange some shoes that her grandmother bought her. Immediately, I'm overwhelmed because I look and feel like shit, and there's all these perfect-looking people giving me the side-eye. Just as I start to go into some shame, a pop song starts playing and Ellen breaks out into the robot. I mean full-on, unfiltered, unaware-just sheer joy. As the perfect people start staring at her, I'm reduced to this moment where I have to decide, Am I going to betray her and roll my eyes and say, "Ellen, settle down," or am I just going to let her do her thing-let her be joyful and unashamed? I end up choosing her and actually dancing with her. It's a great story about choosing my daughter over acceptance by strangers, but I've shopped with enough Bla...

Brené Brown: We could start the story of this book when you texted me to ask if we could talk, and I thought you wanted to continue our ongoing conversation about wallpaper and landscaping-but what came before that? When did the idea for this book come to you?

Tarana Burke: It was after we did SharetheMic on social media, in the summer of 2020. There had been this intense public unrest happening in the country after George Floyd and Breonna Taylor were murdered. In private, I was having these really heartfelt conversations with Black folks who were just struggling: I can't watch any more of this. I can't take this anymore. I cannot . . . And in public, the conversation was, How can we get white people to be better? How can we get white people to be antiracist? Antiracism became the order of the day. But there was no focus on Black humanity. I kept thinking, Where's the space for us to talk about what this does to us, how this affects our lives? And so I was thinking to myself that I really wanted to have a conversation with you.

At first, I struggled to text you. I kept asking myself, Why am I hesitating to reach out to her? We have a close enough friendship to talk about anything. Your work is so important to me and my experience as a human being, but as a Black woman, I often felt like I had to contort myself to fit into the work and see myself in it. I wanted to talk to you about adding to it: "What is the Black experience with shame resilience?" Because white supremacy has added another layer to the kind of shame we have to deal with, and the kind of resilience we have to build, and the kind of vulnerability that we are constantly subjected to whether we choose it or not.

So, yeah, I called and said all of that-but I was not as eloquent [laughter] at the time. I will never forget that phone call. I texted, Can we talk? and you texted back, Sure. Once we got on the phone and I shared the idea, the first thing you said was "Oh, hell yeah. Oh, absolutely! Yes, I want to talk about that. Yes, I want to do this." At that point I was just thinking, Oh, and here I was worrying about offending you and wanting to have a real conversation. So, that was the beginning from my side. What was happening on your side?

Brené: From my side, well, admittedly, I'd probably do anything you ask me to do. But the timing was bigger than us. I had really been grappling over the last couple of years with trying to figure out how to be more inclusive-how to present the work in a way that invited more people to see themselves. The last thing I ever wanted to do was put work in the world around shame, vulnerability, and courage, then make people feel like they had to do something extra to find themselves in it. I thought I had controlled for that with my sample, because I've always been hypervigilant about diversity in the people I interview and in data sources. In fact, one of the early criticisms of my work was that the sample population actually overindexed around Black women and Latinx folks. But I started to get comments, especially from Black women and men: "I had to work at it more to see myself in it than I would have preferred or I would have liked to or than I even should have had to." Finally, it was the combination of a conversation with you and a conversation with Austin Channing Brown on her TV show, where I thought, The problem isn't the research. The research resonates with a diverse group of people because it's based on a diverse sample. But the way I present my research to the world does not always resonate because I often use myself and my stories as examples, and I have a very privileged white experience. That was the huge aha for me.

Tarana: Yeah, that makes sense.

Brené: One of the things that struck me was, in The Gifts of Imperfection, there's a scene where I'm in sweats and have dirty hair and I'm running up the Nordstrom escalator with my daughter to exchange some shoes that her grandmother bought her. Immediately, I'm overwhelmed because I look and feel like shit, and there's all these perfect-looking people giving me the side-eye. Just as I start to go into some shame, a pop song starts playing and Ellen breaks out into the robot. I mean full-on, unfiltered, unaware-just sheer joy. As the perfect people start staring at her, I'm reduced to this moment where I have to decide, Am I going to betray her and roll my eyes and say, "Ellen, settle down," or am I just going to let her do her thing-let her be joyful and unashamed? I end up choosing her and actually dancing with her. It's a great story about choosing my daughter over acceptance by strangers, but I've shopped with enough Bla...