Death & Grief

- Publisher : Milkweed Editions; Illustrated edition

- Published : 30 Mar 2021

- Pages : 248

- ISBN-10 : 1571313834

- ISBN-13 : 9781571313836

- Language : English

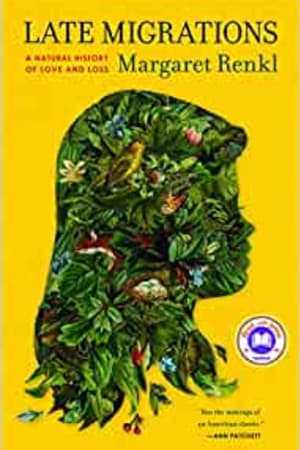

Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss

Selected as a TODAY Show #ReadWithJenna book club pick, Late Migrations is an unusual, captivating portrait of a family―and of the cycles of joy and grief that inscribe human lives within the natural world―from beloved New York Times contributing opinion writer Margaret Renkl.

Growing up in Alabama, Renkl was a devoted reader, an explorer of riverbeds and red-dirt roads, and a fiercely loved daughter. Here, in brief essays, she traces a tender and honest portrait of her complicated parents―her exuberant, creative mother; her steady, supportive father―and of the bittersweet moments that accompany a child's transition to caregiver.

And here, braided into the overall narrative, Renkl offers observations on the world surrounding her suburban Nashville home. Ringing with rapture and heartache, these essays convey the dignity of bluebirds and rat snakes, monarch butterflies and native bees. As these two threads haunt and harmonize with each other, Renkl suggests that there is astonishment to be found in common things: in what seems ordinary, in what we all share. For in both worlds―the natural one and our own―"the shadow side of love is always loss, and grief is only love's own twin."

Gorgeously illustrated by the author's brother, Billy Renkl, Late Migrations is an assured and memorable debut.

Growing up in Alabama, Renkl was a devoted reader, an explorer of riverbeds and red-dirt roads, and a fiercely loved daughter. Here, in brief essays, she traces a tender and honest portrait of her complicated parents―her exuberant, creative mother; her steady, supportive father―and of the bittersweet moments that accompany a child's transition to caregiver.

And here, braided into the overall narrative, Renkl offers observations on the world surrounding her suburban Nashville home. Ringing with rapture and heartache, these essays convey the dignity of bluebirds and rat snakes, monarch butterflies and native bees. As these two threads haunt and harmonize with each other, Renkl suggests that there is astonishment to be found in common things: in what seems ordinary, in what we all share. For in both worlds―the natural one and our own―"the shadow side of love is always loss, and grief is only love's own twin."

Gorgeously illustrated by the author's brother, Billy Renkl, Late Migrations is an assured and memorable debut.

Editorial Reviews

Praise for Late Migrations

A Barnes & Noble Our Monthly Pick selection for April 2021

A TODAY Show #ReadWithJenna Book Club Pick

Winner of 2020 Phillip D. Reed Environmental Writing Award

Finalist for the Southern Book Prize

Named a "Best Book of the Year" by New Statesman, New York Public Library, Chicago Public Library, Foreword Reviews, and Washington Independent Review of Books

An Indie Next Selection, Indies Introduce Selection, and Okra Pick

"Beautifully written, masterfully structured, and brimming with insight into the natural world, Late Migrations can claim its place alongside Pilgrim at Tinker Creek and A Death in the Family. It has the makings of an American classic."―Ann Patchett, author of Commonwealth

"[Renkl] is the most beautiful writer! I love this book. It's about the South, and growing up there, and about her love of nature and animals and her wonderful family."―Reese Witherspoon

"Reflective and gorgeous . . . I have recommended this book to everybody that I know. It is a beautiful book about love, and [how] . . . to find the beauty in the little things."―Jenna Bush Hager, the TODAY Show

"A perfect book to read in the summer . . . This is the kind of writing that makes me just want to stay put, reread and savor everything about that moment."―Maureen Corrigan, NPR's Fresh Air

"Equal parts Annie Dillard and Anne Lamott with a healthy sprinkle of Tennessee dry rub thrown in."―New York Times Book Review

"A compact glory, crosscutting between consummate family memoir and keenly observed backyard natural history. Renkl's deft juxtapositions close up the gap between humans and nonhumans and revive our lost kinship with other living things."―Richard Powers, author of The Overstory

"Magnificent . . . Conjure your favorite place in the natural world: beach, mountain, lake, forest, porch, windowsill rooftop? Precisely there is the best place in which to savor this book."―NPR.org

"Late Migrations has echoes of Annie Dillard's The Writing Life―with grandparents, sons, dogs and birds sharing the spotlight, it's a witty, warm and unaccountably soothing all-American story."―People

"[Renkl] guides us through a South lush with bluebirds, pecan orchards, and glasses of whiskey shared at dusk in this collection of prose in poetry-size bits; as it celebrates bounty, it also mourns the profound losses we face every day."―O, the Oprah Magazine

"Graceful . . . Like a belated answer to [E.B.] White."―Wall Street Journal

"A lovely collection of essays about life, nature, and family. It will...

A Barnes & Noble Our Monthly Pick selection for April 2021

A TODAY Show #ReadWithJenna Book Club Pick

Winner of 2020 Phillip D. Reed Environmental Writing Award

Finalist for the Southern Book Prize

Named a "Best Book of the Year" by New Statesman, New York Public Library, Chicago Public Library, Foreword Reviews, and Washington Independent Review of Books

An Indie Next Selection, Indies Introduce Selection, and Okra Pick

"Beautifully written, masterfully structured, and brimming with insight into the natural world, Late Migrations can claim its place alongside Pilgrim at Tinker Creek and A Death in the Family. It has the makings of an American classic."―Ann Patchett, author of Commonwealth

"[Renkl] is the most beautiful writer! I love this book. It's about the South, and growing up there, and about her love of nature and animals and her wonderful family."―Reese Witherspoon

"Reflective and gorgeous . . . I have recommended this book to everybody that I know. It is a beautiful book about love, and [how] . . . to find the beauty in the little things."―Jenna Bush Hager, the TODAY Show

"A perfect book to read in the summer . . . This is the kind of writing that makes me just want to stay put, reread and savor everything about that moment."―Maureen Corrigan, NPR's Fresh Air

"Equal parts Annie Dillard and Anne Lamott with a healthy sprinkle of Tennessee dry rub thrown in."―New York Times Book Review

"A compact glory, crosscutting between consummate family memoir and keenly observed backyard natural history. Renkl's deft juxtapositions close up the gap between humans and nonhumans and revive our lost kinship with other living things."―Richard Powers, author of The Overstory

"Magnificent . . . Conjure your favorite place in the natural world: beach, mountain, lake, forest, porch, windowsill rooftop? Precisely there is the best place in which to savor this book."―NPR.org

"Late Migrations has echoes of Annie Dillard's The Writing Life―with grandparents, sons, dogs and birds sharing the spotlight, it's a witty, warm and unaccountably soothing all-American story."―People

"[Renkl] guides us through a South lush with bluebirds, pecan orchards, and glasses of whiskey shared at dusk in this collection of prose in poetry-size bits; as it celebrates bounty, it also mourns the profound losses we face every day."―O, the Oprah Magazine

"Graceful . . . Like a belated answer to [E.B.] White."―Wall Street Journal

"A lovely collection of essays about life, nature, and family. It will...

Readers Top Reviews

Kindle Susan

It took me a while to catch on, then the essays were understood to be contributing to a larger narrative of a thoughtful life, life and death braided in the attention of a skilled writer. Verging on cliche, I laughed and cried and grew in spirit.

LetterPress

A book of days, of stories, of wonderful prose and observations, I am intensely glad Ms. Renkl wrote this book. Thank you for a gift I will read again and again.

Krazee Dog Ladydemer

Based upon the recent press and the other 5 star reviews, I really wanted to like and devour this book. No such luck. It's boring and uninteresting, skips around enough to be confusing. And not enough character development to be able to care about any of the characters. I think the author is trying to impress us with her 'intellectual' yet creative writing style, open our eyes to the wonders of nature, the importance of family, blah, blah, blah.... If you enjoy birds, storms and death, you may like it. I couldn't even make it halfway through. Returned it.

Ann Wilson Green

I recently learned of the concept of a "spark bird"--a bird spotting which ignites an interest in birding and profoundly changes the way you think about birds. On a simple level, Margaret Renkl's "Late Migrations" most certainly peaked my interest in birds--and nature in general. But on a deeper level, it does what great writing does--it changed the way I look at loss and life. On a deeper level, then, it is a "spark bird" of a book. It is also a rare sighting of simple prose, effortless to read yet, Renkl's metaphors stop you cold with their depth and beauty. I can't recommend this book more highly.

Terre Greer

The author came to an independent bookstore in my town for a reading and signing and after meeting her and hearing her read from it, I devoured the book in one or two sittings. I found her writing to be lyrical, poetic and oh so beautiful. I found the characters to be so vividly portrayed that I felt I could visualize them and imagine the voices in the conversations. I found the interweaving of the stories of death in the natural world and death in the immediate family of the author to be inspired. The author’s stories and experiences made me feel less afraid, less alone, and less unique in the difficulties of dealing with role reversal in caring for an elderly parent. I have also been enjoying Renkl’s NYT columns. Her piece last summer about menopause was genius. I have purchased a half dozen copies and given them as gifts and plan to give more as gifts when the holidays come around. I can’t wait to read what she writes next.

Short Excerpt Teaser

TWILIGHT

AUBURN, 1982

I went to a land-grant university, a rural school that students at the rival institution dismissed as a cow college, though I was a junior before I ever saw a single cow there. For someone who had spent her childhood almost entirely outdoors, my college life was unacceptably enclosed. Every day I followed the same brick path from crowded dorm to crowded class to crowded office to rowded cafeteria, and then back to the dorm again. A gentler terrain of fields and ponds and piney woods existed less than a mile from the liberal arts high-rise, but I had no time for idle exploring, for poking about in the scaled-down universe where forestry and agriculture students learned their trade.

One afternoon late in the fall of my junior year, I broke. I had stopped at the cafeteria to grab a sandwich before the dinner crowd hit, hoping for a few minutes of quiet in which to read my literature assignment, the poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins, before my evening shift at the dorm desk. But even with few students present, there was nothing resembling quiet in that cavernous room. The loudspeaker blasted John Cougar's ditty about Jack and Diane, and I pressed my fingers into my ears and hunched low over my book. The sound of my own urgent blood thumping through my veins quarreled with the magnificent sprung rhythm of the poem as thoroughly as Jack and Diane did, and I finally snapped the book closed. My heart was still pounding as I stepped into the dorm lobby, ditched my pack, and started walking. I was headed out.

It was a delight to be moving, to feel my body expanding into the larger gestures of the outdoors. What a relief to feel my walk lengthening into a stride and my lungs taking in air by the gulp. I kept walking―past the football stadium, past the sororities―until I came to the red dirt lanes of the agriculture program's experimental fields. Brindled cows turned their unsurprised faces toward me in pastures dotted with hay bales that looked like giant spools of golden thread. The empty bluebird boxes nailed to the fence posts were shining in the slanted light. A red-tailed hawk―the only kind I could name―glided past, calling into the sky.

I caught my breath and walked on, with a rising sense that glory was all around me. Only at twilight can an ordinary mortal walk in light and dark at once―feet plodding through night, eyes turned up toward bright day. It is a glimpse into eternity, that bewildering notion of endless time, where light and dark exist simultaneously.

When the fields gave way to the experimental forest, the wind had picked up, and dogwood leaves were lifting and falling in the light. There are few sights lovelier than leaves being carried on wind. Though that sight was surely common on the campus quad, I had somehow failed to register it. And the swifts wheeling in the sky as evening came on―they would be visible to anyone standing on the sidewalk outside Haley Center, yet I had missed them, too.

There, in that forest, I heard the sound of trees giving themselves over to night. Long after I turned in my paper on Hopkins, long after I was gone myself, this goldengrove unleaving would be releasing its bounty to the wind.

***

BABEL

PHILADELPHIA, 1984

I thought I had escaped the beautiful, benighted South for good when I left Alabama for graduate school in Philadelphia in 1984, though now I can't imagine how this delusion ever took root. At the age of twenty-two, I had never set foot any farther north than Chattanooga, Tennessee. By the time I got to Philadelphia, I was so poorly traveled―and so geographically illiterate―I could not pick out the state of Pennsylvania on an unlabeled weather map on the evening news.

I can't even say why I thought I should get a doctorate in English. The questions that occupy scholars―details of textuality, previously unnoted formative influences, nuances of historical context―held no interest for me. Why hadn't I applied to writing programs instead? Some vague idea about employability, maybe.

When I tell people, if it ever comes up, that I once spent a semester in Philadelphia, a knot instantly forms in the back of my throat, a reminder across thirty years of the panic and despair I felt with every step I took on those grimy sidewalks, with every breath of that heavy, exhaust-burdened air. I had moved into a walkup on a main artery of West Philly, and I lay awake that first sweltering night with the windows open to catch what passed for a breeze, waiting for the sounds of traffic to die down. They never did. All night long, the gears of delivery trucks ground at the traffic light on the corner; four floors down, strangers muttered and swore in the darkness.

Everywhere in ...

AUBURN, 1982

I went to a land-grant university, a rural school that students at the rival institution dismissed as a cow college, though I was a junior before I ever saw a single cow there. For someone who had spent her childhood almost entirely outdoors, my college life was unacceptably enclosed. Every day I followed the same brick path from crowded dorm to crowded class to crowded office to rowded cafeteria, and then back to the dorm again. A gentler terrain of fields and ponds and piney woods existed less than a mile from the liberal arts high-rise, but I had no time for idle exploring, for poking about in the scaled-down universe where forestry and agriculture students learned their trade.

One afternoon late in the fall of my junior year, I broke. I had stopped at the cafeteria to grab a sandwich before the dinner crowd hit, hoping for a few minutes of quiet in which to read my literature assignment, the poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins, before my evening shift at the dorm desk. But even with few students present, there was nothing resembling quiet in that cavernous room. The loudspeaker blasted John Cougar's ditty about Jack and Diane, and I pressed my fingers into my ears and hunched low over my book. The sound of my own urgent blood thumping through my veins quarreled with the magnificent sprung rhythm of the poem as thoroughly as Jack and Diane did, and I finally snapped the book closed. My heart was still pounding as I stepped into the dorm lobby, ditched my pack, and started walking. I was headed out.

It was a delight to be moving, to feel my body expanding into the larger gestures of the outdoors. What a relief to feel my walk lengthening into a stride and my lungs taking in air by the gulp. I kept walking―past the football stadium, past the sororities―until I came to the red dirt lanes of the agriculture program's experimental fields. Brindled cows turned their unsurprised faces toward me in pastures dotted with hay bales that looked like giant spools of golden thread. The empty bluebird boxes nailed to the fence posts were shining in the slanted light. A red-tailed hawk―the only kind I could name―glided past, calling into the sky.

I caught my breath and walked on, with a rising sense that glory was all around me. Only at twilight can an ordinary mortal walk in light and dark at once―feet plodding through night, eyes turned up toward bright day. It is a glimpse into eternity, that bewildering notion of endless time, where light and dark exist simultaneously.

When the fields gave way to the experimental forest, the wind had picked up, and dogwood leaves were lifting and falling in the light. There are few sights lovelier than leaves being carried on wind. Though that sight was surely common on the campus quad, I had somehow failed to register it. And the swifts wheeling in the sky as evening came on―they would be visible to anyone standing on the sidewalk outside Haley Center, yet I had missed them, too.

There, in that forest, I heard the sound of trees giving themselves over to night. Long after I turned in my paper on Hopkins, long after I was gone myself, this goldengrove unleaving would be releasing its bounty to the wind.

***

BABEL

PHILADELPHIA, 1984

I thought I had escaped the beautiful, benighted South for good when I left Alabama for graduate school in Philadelphia in 1984, though now I can't imagine how this delusion ever took root. At the age of twenty-two, I had never set foot any farther north than Chattanooga, Tennessee. By the time I got to Philadelphia, I was so poorly traveled―and so geographically illiterate―I could not pick out the state of Pennsylvania on an unlabeled weather map on the evening news.

I can't even say why I thought I should get a doctorate in English. The questions that occupy scholars―details of textuality, previously unnoted formative influences, nuances of historical context―held no interest for me. Why hadn't I applied to writing programs instead? Some vague idea about employability, maybe.

When I tell people, if it ever comes up, that I once spent a semester in Philadelphia, a knot instantly forms in the back of my throat, a reminder across thirty years of the panic and despair I felt with every step I took on those grimy sidewalks, with every breath of that heavy, exhaust-burdened air. I had moved into a walkup on a main artery of West Philly, and I lay awake that first sweltering night with the windows open to catch what passed for a breeze, waiting for the sounds of traffic to die down. They never did. All night long, the gears of delivery trucks ground at the traffic light on the corner; four floors down, strangers muttered and swore in the darkness.

Everywhere in ...