Death & Grief

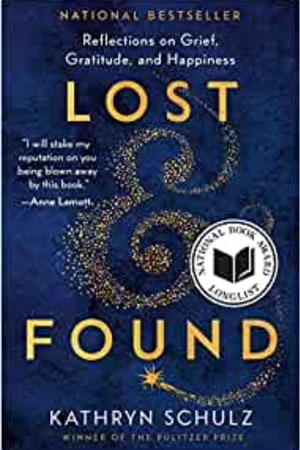

- Publisher : Random House Trade Paperbacks

- Published : 22 Nov 2022

- Pages : 272

- ISBN-10 : 0525512489

- ISBN-13 : 9780525512486

- Language : English

Lost & Found: Reflections on Grief, Gratitude, and Happiness

NATIONAL BESTSELLER • NEW YORK TIMES EDITORS' CHOICE • A "profound and beautiful" (Marilynne Robinson) account of joy and sorrow from one of the great writers of our time, The New Yorker's Kathryn Schulz, winner of the Pulitzer Prize

"I will stake my reputation on you being blown away by Lost & Found."-Anne Lamott, author of Dusk, Night, Dawn and Bird by Bird

LONGLISTED FOR THE NATIONAL BOOK AWARD • LONGLISTED FOR THE ANDREW CARNEGIE MEDAL

ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR: Time, NPR, The Washington Post, Publishers Weekly

One spring morning, Kathryn Schulz went to lunch with a stranger and fell in love. Having spent years looking for the right relationship, she was dazzled by how swiftly everything changed when she finally met her future wife. But as the two of them began building a life together, Schulz's beloved father-a charming, brilliant, absentminded Jewish refugee-went into the hospital with a minor heart condition and never came out. Newly in love yet also newly bereft, Schulz was left contending simultaneously with wild joy and terrible grief.

Those twin experiences form the heart of Lost & Found, a profound meditation on the families that make us and the families we make. But Schulz's book also explores how disappearance and discovery shape us all. On average, we each lose two hundred thousand objects over our lifetime, and Schulz brilliantly illuminates the relationship between those everyday losses and our most devastating ones. Likewise, she explores the importance of seeking, whether for ancient ruins or new ideas, friends, faith, meaning, or love. The resulting book is part memoir, part guidebook to sustaining wonder and gratitude even in the face of loss and grief. A staff writer at The New Yorker and winner of the Pulitzer Prize, Schulz writes with curiosity, tenderness, and humor about the connections between joy and sorrow-and between us all.

"I will stake my reputation on you being blown away by Lost & Found."-Anne Lamott, author of Dusk, Night, Dawn and Bird by Bird

LONGLISTED FOR THE NATIONAL BOOK AWARD • LONGLISTED FOR THE ANDREW CARNEGIE MEDAL

ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR: Time, NPR, The Washington Post, Publishers Weekly

One spring morning, Kathryn Schulz went to lunch with a stranger and fell in love. Having spent years looking for the right relationship, she was dazzled by how swiftly everything changed when she finally met her future wife. But as the two of them began building a life together, Schulz's beloved father-a charming, brilliant, absentminded Jewish refugee-went into the hospital with a minor heart condition and never came out. Newly in love yet also newly bereft, Schulz was left contending simultaneously with wild joy and terrible grief.

Those twin experiences form the heart of Lost & Found, a profound meditation on the families that make us and the families we make. But Schulz's book also explores how disappearance and discovery shape us all. On average, we each lose two hundred thousand objects over our lifetime, and Schulz brilliantly illuminates the relationship between those everyday losses and our most devastating ones. Likewise, she explores the importance of seeking, whether for ancient ruins or new ideas, friends, faith, meaning, or love. The resulting book is part memoir, part guidebook to sustaining wonder and gratitude even in the face of loss and grief. A staff writer at The New Yorker and winner of the Pulitzer Prize, Schulz writes with curiosity, tenderness, and humor about the connections between joy and sorrow-and between us all.

Editorial Reviews

"In an ocean of churning cynicism and despair, this is a winning bet."-The New York Times

"Sublime, compassionate . . . brilliant."-Minneapolis Star-Tribune

"Lost & Found exemplifies the best of what memoir can do."-Oprah Daily

"An extraordinary gift of a book, a tender, searching meditation on love and loss and what it means to be human. I wept at it, laughed with it, was entirely fascinated by it. I emerged feeling as if the world around me had been made anew."-Helen Macdonald, author of H Is for Hawk and Vesper Flights

"An unfolding astonishment to read."-Alison Bechdel, author of The Secret to Human Strength and Fun Home

"Kathryn Schulz has created a masterpiece of metaphysical insight, at once richly lyrical and piercingly specific."-Andrew Solomon, author of The Noonday Demon and Far from the Tree

"Our lives do indeed deserve and reward the kind of honest, gentle, brilliant scrutiny Schulz brings to bear on her own life. The book is profound and beautiful."-Marilynne Robinson, author of Housekeeping and Gilead

"Lost & Found is the most daring of books: a memoir by a happy person. Deeply felt and exquisitely written, it's an absorbing exploration of love and loss-not to mention meteorites, Dante, and bears. The prodigiously talented Kathryn Schulz has written about her life in a way that will change yours."-Andy Borowitz, of "The Borowitz Report"

"Lost & Found is a deeply moving, richly illuminating exploration of loss and bliss. Schulz is never anything but the very best company, speaking nuanced truths...

"Sublime, compassionate . . . brilliant."-Minneapolis Star-Tribune

"Lost & Found exemplifies the best of what memoir can do."-Oprah Daily

"An extraordinary gift of a book, a tender, searching meditation on love and loss and what it means to be human. I wept at it, laughed with it, was entirely fascinated by it. I emerged feeling as if the world around me had been made anew."-Helen Macdonald, author of H Is for Hawk and Vesper Flights

"An unfolding astonishment to read."-Alison Bechdel, author of The Secret to Human Strength and Fun Home

"Kathryn Schulz has created a masterpiece of metaphysical insight, at once richly lyrical and piercingly specific."-Andrew Solomon, author of The Noonday Demon and Far from the Tree

"Our lives do indeed deserve and reward the kind of honest, gentle, brilliant scrutiny Schulz brings to bear on her own life. The book is profound and beautiful."-Marilynne Robinson, author of Housekeeping and Gilead

"Lost & Found is the most daring of books: a memoir by a happy person. Deeply felt and exquisitely written, it's an absorbing exploration of love and loss-not to mention meteorites, Dante, and bears. The prodigiously talented Kathryn Schulz has written about her life in a way that will change yours."-Andy Borowitz, of "The Borowitz Report"

"Lost & Found is a deeply moving, richly illuminating exploration of loss and bliss. Schulz is never anything but the very best company, speaking nuanced truths...

Readers Top Reviews

Lindsay HurtyMUSA

I loved this book. I listened to it, then bought a copy. Smart, thoughtful, profoundly vulnerable. Beautiful writing.

NancyLindsay Hurt

A beautiful treatise on life and death and the stuff in between. Provokes both smiles and tears, a genuine treasure.

RobNancyLindsay H

I wanted to like this a lot more. The author is a wonderful writer, and the story is heartwarming and hopeful. I bought the book having enjoyed a piece the author wrote in the New Yorker last year, and noting advance blurbs promising "a masterpiece of metaphysical insight." I didn't find it to be quite that. It's a meditation, deeply personal, on the most foundational aspects of human experience. The "And" chapter in particular was unexpected and novel. Drawing from William James, Schultz weaves a pluralistic, contingent, and living ontology in which all things are relational. It's an inspiring vision, far more so than the "atomistic" worldview that James opposed. It's a universe in which the simple union of things creates meaning. Ultimately, however, I didn't find that the book broke any new ground. Insightful and easy, I'd recommend the book for a quick read, but if like me, you were excited by the blurbs, temper your expectations.

writer30033RobNan

KS is a superb writer. Here she takes on broad subjects (loss, death, discovery, love) and makes them intimate and personal. Then throws a meteorite or two into the narrative. Love is particularly difficult to capture well. She goes big and boom, if you have been in love, you are in that stage again, with her and C. We are fortunate to be reading at a time when she is writing. Keep going, KS.

Dr Danwriter30033

Lost. Found. Lost and Found. The first part of the book is deeply emotional. It connected so deeply to my own experience of loss there were times when I had to put the book down and gather myself. The last section in its reflection of “and” as both connecting and anticipating was equally rich. Though Schultz doesn’t write from an overtly religious, much less Christian, perspective, her closing words on life’s inevitable transitoriness strike me as some of the most evocative theological reflection: “…….we are here above all as caretakers, a role as essential as it is temporary. None of us would be here without what came before us, and none of us can know how much and in what ways everything that will come after us depends upon our being here.” Of note is her insight about consolation in grief: to simply behold the moment in which we have life and breath. This is a quote worthy book comprised of three essays. Lost. And. Found.

Short Excerpt Teaser

Chapter 1

I have always disliked euphemisms for dying. "Passed away," "gone home," "no longer with us," "departed": although language like this is well-intentioned, it has never brought me any solace. In the name of tact, it turns away from death's shocking bluntness; in the name of comfort, it chooses the safe and familiar over the beautiful or evocative. To me, all this feels evasive, like a verbal averting of the eyes. But death is so impossible to avoid-that is the basic, bedrock fact of it-that trying to talk around it seems misguided. As the poet Robert Lowell wrote, "Why not say what happened?"

Yet there is one exception to this preference of mine. "I lost my father": he had barely been dead ten days when I first heard myself use that expression. I was home again by then, after the long unmoored weeks by his side in the hospital, after the death, after the memorial service, thrust back into a life that looked exactly as it had before I left, orderly and daylit, its mundane obligations rendered exhausting by grief. My phone was lodged between my shoulder and my chin. While my father had been in a cardiac unit and then an intensive care unit and then in hospice care, dying, I had received a series of automated messages from the magazine where I work, informing me that I would be locked out of my email if I did not change my password. These arrived with clockwork regularity, reminding me that my access would expire in ten days, in nine days, in eight days, in seven days. It is remarkable how the ordinary and the existential are always stuck together, like the pages in a book so timeworn that the print has transferred from one to the other. I did not fix the password problem. I did lose the access and, with it, any means to solve the problem on my own. And so, after my father died, I found myself on the phone with a customer service representative, explaining, although it was absolutely unnecessary to do so, why I had neglected to address the issue in a timely fashion.

I lost my father last week. Perhaps because I was still in those early, distorted days of mourning, when so much of the familiar world feels alien and inaccessible, I was struck, as I had never been before, by the strangeness of the phrase. Obviously my father hadn't wandered away from me like a toddler at a picnic, or vanished like an important document in a messy office. And yet, unlike other oblique ways of talking about death, this one did not seem cagey or empty. It seemed plain, plaintive, and lonely, like grief itself. From the first time I said it, that day on the phone, it felt like something I could use, as one uses a shovel or a bell-pull: cold and ringing, containing within it both something desperate and something resigned, accurate to the confusion and desolation of bereavement.

Later, when I looked it up, I learned that there was a reason "lost" felt so apt to me. I had always assumed that, if we were referring to the dead we were using the word figuratively-that it had been appropriated by those in mourning and contorted far beyond its original meaning. But that turns out not to be true. The verb "to lose" has its taproot sunk in sorrow; it is related to the "lorn" in "forlorn." It comes from an Old English word meaning to perish, which comes from an even older word meaning to separate or cut apart. The modern sense of misplacing an object only appeared later, in the thirteenth century; a hundred years after that, "to lose" acquired the meaning of failing to win. In the sixteenth century we began to lose our minds; in the seventeenth century, our hearts. The circle of what we can lose, in other words, began with our own lives and each other and has been steadily expanding ever since.

This is how loss felt to me after my father died: like a force that constantly increased its reach, gradually encroaching on more and more terrain. Eventually I found myself keeping a list of all the other things I had lost over time as well, chiefly because they kept coming back to mind. A childhood toy, a childhood friend, a beloved cat who went outside one day and never returned, the letter my grandmother wrote me when I graduated from college, a threadbare but perfect blue plaid shirt, a journal I'd kept for the better part of five years: on and on it went, a kind of anti-collection, a melancholy catalogue of everything of mine that had ever gone missing.

Any list like this-and all of us have one-quickly reveals the strangeness of the category of loss: how enormous and awkward it is, how little else its contents have in common. I was surprised to realize, when I first began thinking about it, that some kinds of loss are actually positive. We can lose our self-consciousness and our fear, and although it is fr...

I have always disliked euphemisms for dying. "Passed away," "gone home," "no longer with us," "departed": although language like this is well-intentioned, it has never brought me any solace. In the name of tact, it turns away from death's shocking bluntness; in the name of comfort, it chooses the safe and familiar over the beautiful or evocative. To me, all this feels evasive, like a verbal averting of the eyes. But death is so impossible to avoid-that is the basic, bedrock fact of it-that trying to talk around it seems misguided. As the poet Robert Lowell wrote, "Why not say what happened?"

Yet there is one exception to this preference of mine. "I lost my father": he had barely been dead ten days when I first heard myself use that expression. I was home again by then, after the long unmoored weeks by his side in the hospital, after the death, after the memorial service, thrust back into a life that looked exactly as it had before I left, orderly and daylit, its mundane obligations rendered exhausting by grief. My phone was lodged between my shoulder and my chin. While my father had been in a cardiac unit and then an intensive care unit and then in hospice care, dying, I had received a series of automated messages from the magazine where I work, informing me that I would be locked out of my email if I did not change my password. These arrived with clockwork regularity, reminding me that my access would expire in ten days, in nine days, in eight days, in seven days. It is remarkable how the ordinary and the existential are always stuck together, like the pages in a book so timeworn that the print has transferred from one to the other. I did not fix the password problem. I did lose the access and, with it, any means to solve the problem on my own. And so, after my father died, I found myself on the phone with a customer service representative, explaining, although it was absolutely unnecessary to do so, why I had neglected to address the issue in a timely fashion.

I lost my father last week. Perhaps because I was still in those early, distorted days of mourning, when so much of the familiar world feels alien and inaccessible, I was struck, as I had never been before, by the strangeness of the phrase. Obviously my father hadn't wandered away from me like a toddler at a picnic, or vanished like an important document in a messy office. And yet, unlike other oblique ways of talking about death, this one did not seem cagey or empty. It seemed plain, plaintive, and lonely, like grief itself. From the first time I said it, that day on the phone, it felt like something I could use, as one uses a shovel or a bell-pull: cold and ringing, containing within it both something desperate and something resigned, accurate to the confusion and desolation of bereavement.

Later, when I looked it up, I learned that there was a reason "lost" felt so apt to me. I had always assumed that, if we were referring to the dead we were using the word figuratively-that it had been appropriated by those in mourning and contorted far beyond its original meaning. But that turns out not to be true. The verb "to lose" has its taproot sunk in sorrow; it is related to the "lorn" in "forlorn." It comes from an Old English word meaning to perish, which comes from an even older word meaning to separate or cut apart. The modern sense of misplacing an object only appeared later, in the thirteenth century; a hundred years after that, "to lose" acquired the meaning of failing to win. In the sixteenth century we began to lose our minds; in the seventeenth century, our hearts. The circle of what we can lose, in other words, began with our own lives and each other and has been steadily expanding ever since.

This is how loss felt to me after my father died: like a force that constantly increased its reach, gradually encroaching on more and more terrain. Eventually I found myself keeping a list of all the other things I had lost over time as well, chiefly because they kept coming back to mind. A childhood toy, a childhood friend, a beloved cat who went outside one day and never returned, the letter my grandmother wrote me when I graduated from college, a threadbare but perfect blue plaid shirt, a journal I'd kept for the better part of five years: on and on it went, a kind of anti-collection, a melancholy catalogue of everything of mine that had ever gone missing.

Any list like this-and all of us have one-quickly reveals the strangeness of the category of loss: how enormous and awkward it is, how little else its contents have in common. I was surprised to realize, when I first began thinking about it, that some kinds of loss are actually positive. We can lose our self-consciousness and our fear, and although it is fr...