World

- Publisher : Random House

- Published : 02 May 2023

- Pages : 336

- ISBN-10 : 0385353987

- ISBN-13 : 9780385353984

- Language : English

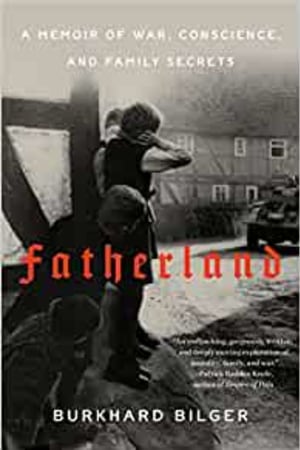

Fatherland: A Memoir of War, Conscience, and Family Secrets

A New Yorker staff writer investigates his grandfather, a Nazi Party Chief, in this "unflinching, gorgeously written, and deeply moving exploration of morality, family, and war" (Patrick Radden Keefe, author of Empire of Pain).

As a boy growing up in Oklahoma, Burkhard Bilger often heard his parents tell stories about the Germany of their youth. Winters in the Black Forest, when the snow piled up to the eaves and haunches of smoked speck hung from the rafters. Springtime along the Rhine, when the storks came home to nest on rooftops. His parents were born in 1935 and had lived through the Second World War, but those stories, vivid as they were, had strange omissions. His mother was a historian, yet she rarely talked about her father's relationship to the Nazis, or his role in the war. Then one day a packet of letters arrived from Germany, yellowed with age, and a secret history began to unfold.

Karl Gönner was an elementary school teacher and father of four when the war began. In 1940, he was posted to a village in Alsace, in occupied France, and ordered to reeducate its children-to turn them into proper Germans. He was a loyal Nazi when he arrived, but as the war went on his allegiance wavered. According to some villagers, he risked his life shielding them from his own party's brutalities. According to others, he ruled the village with an iron fist. After the war, Gönner was charged with giving an order that led police to beat a local farmer to death. Was he guilty or innocent? A war criminal or just an ordinary man, struggling to do right from within a monstrous regime?

Fatherland is the story of Bilger's nearly ten-year quest to uncover the truth. It is a book of gripping suspense and moral inquiry-a tale of chance encounters and serendipitous discoveries in archives and villages across Germany and France. Long admired for his profiles in The New Yorker, Bilger brings the same open-hearted curiosity to his grandfather's story and the questions it raises. What do we owe the past? How can we make peace with it without perpetuating its wrongs? Intimate and far-reaching, Fatherland is an extraordinary odyssey through the great upheavals of the past century.

As a boy growing up in Oklahoma, Burkhard Bilger often heard his parents tell stories about the Germany of their youth. Winters in the Black Forest, when the snow piled up to the eaves and haunches of smoked speck hung from the rafters. Springtime along the Rhine, when the storks came home to nest on rooftops. His parents were born in 1935 and had lived through the Second World War, but those stories, vivid as they were, had strange omissions. His mother was a historian, yet she rarely talked about her father's relationship to the Nazis, or his role in the war. Then one day a packet of letters arrived from Germany, yellowed with age, and a secret history began to unfold.

Karl Gönner was an elementary school teacher and father of four when the war began. In 1940, he was posted to a village in Alsace, in occupied France, and ordered to reeducate its children-to turn them into proper Germans. He was a loyal Nazi when he arrived, but as the war went on his allegiance wavered. According to some villagers, he risked his life shielding them from his own party's brutalities. According to others, he ruled the village with an iron fist. After the war, Gönner was charged with giving an order that led police to beat a local farmer to death. Was he guilty or innocent? A war criminal or just an ordinary man, struggling to do right from within a monstrous regime?

Fatherland is the story of Bilger's nearly ten-year quest to uncover the truth. It is a book of gripping suspense and moral inquiry-a tale of chance encounters and serendipitous discoveries in archives and villages across Germany and France. Long admired for his profiles in The New Yorker, Bilger brings the same open-hearted curiosity to his grandfather's story and the questions it raises. What do we owe the past? How can we make peace with it without perpetuating its wrongs? Intimate and far-reaching, Fatherland is an extraordinary odyssey through the great upheavals of the past century.

Editorial Reviews

"A profoundly haunting work of historical investigation, a reporter's dogged inquiry into the tangled history of his Nazi grandfather . . . Fatherland is an unflinching, gorgeously written, and deeply moving exploration of morality, family, and war."-Patrick Radden Keefe, author of Empire of Pain

"Burkhard Bilger has long been one of our great storytellers: an acute observer, an intrepid reporter, and a writer of unmatched grace. Now he has brought these gifts to his own family story, rummaging through the past to unearth long-kept secrets and to shed light on the nature of war and complicity. Fatherland is that rare book-a finely etched memoir with the powerful sweep of history."-David Grann, author of Killers of the Flower Moon

"Fatherland is the book we need right now. Gripping, gorgeously written, and deeply humane, it's both a moving personal history and a formidable piece of detective work. Bilger wrestles with one of the essential questions of our time: How can we make peace with our ancestors' past?"-Atul Gawande, author of Being Mortal

"Fatherland is an unforgettable book: a family saga set on a global stage. Bilger's fearless search for the truth about his grandfather's role in World War II-and his willingness to take the reader on the journey, regardless of what he may find-is a testament to his skill as both journalist and storyteller. I could not put it down."-Reza Aslan, author of Zealot and An American Martyr in Persia

"Forget the Third Reich of the movies, Bilger's unblinking yet tender exploration of his own family's experiences and memories brilliantly captures the bewildering reality of a time and place we think we already know. Fatherland is a masterful and riveting weave of the personal and the monumental, of ordinary Germans' struggles with questions of identity, responsibility, and sheer survival in a world gone mad."-Joel F. Harrington, Centennial Professor of History at Vanderbilt University and author of The Faithful Executioner

"<...

"Burkhard Bilger has long been one of our great storytellers: an acute observer, an intrepid reporter, and a writer of unmatched grace. Now he has brought these gifts to his own family story, rummaging through the past to unearth long-kept secrets and to shed light on the nature of war and complicity. Fatherland is that rare book-a finely etched memoir with the powerful sweep of history."-David Grann, author of Killers of the Flower Moon

"Fatherland is the book we need right now. Gripping, gorgeously written, and deeply humane, it's both a moving personal history and a formidable piece of detective work. Bilger wrestles with one of the essential questions of our time: How can we make peace with our ancestors' past?"-Atul Gawande, author of Being Mortal

"Fatherland is an unforgettable book: a family saga set on a global stage. Bilger's fearless search for the truth about his grandfather's role in World War II-and his willingness to take the reader on the journey, regardless of what he may find-is a testament to his skill as both journalist and storyteller. I could not put it down."-Reza Aslan, author of Zealot and An American Martyr in Persia

"Forget the Third Reich of the movies, Bilger's unblinking yet tender exploration of his own family's experiences and memories brilliantly captures the bewildering reality of a time and place we think we already know. Fatherland is a masterful and riveting weave of the personal and the monumental, of ordinary Germans' struggles with questions of identity, responsibility, and sheer survival in a world gone mad."-Joel F. Harrington, Centennial Professor of History at Vanderbilt University and author of The Faithful Executioner

"<...

Readers Top Reviews

Short Excerpt Teaser

1

Suspect

The man in the interrogation room had all the marks of a dangerous fanatic: stiff spine and bony shoulders, lips pinched into a pleat. He wore brass spectacles with round, tortoiseshell rims and his head was shaved along the back and sides, leaving a shock of brown hair to flop around on top, like a toupee. When he posed for his mug shot, his expression was strangely unbalanced. The left eye had a flat, unwavering focus, edged with fear or grief. The right eye was glazed and lifeless.

The French inspector, Otto Baumgartner, paced in front of him reading from a typewritten sheet. "In October of 1940, you moved to Alsace and set yourself the task of converting the inhabitants of Bartenheim to National Socialism," he began. "You established yourself as Ortsgruppenleiter in order to become the town's absolute master. . . . You brought to your duties a zeal and a tyrannical fervor without equal! In the entire district of Mulhouse, you were the most feared and infamous of leaders!"

Baumgartner paused after each charge to let the prisoner respond, while another inspector transcribed the exchange. It had been nearly a year since the German surrender, and these men had heard their share of pleas and denunciations. The countryside seethed with military courts and citizens' militias, lynch mobs and makeshift tribunals. For four years, the Nazi occupation had divided France ever more bitterly against itself, turning neighbor against neighbor and Christian against Jew. Now the days of reckoning had come. More than nine thousand people would be executed as war criminals and collaborators over the next five years, in addition to those denounced and beaten; the women shorn and shaved and paraded through towns for sleeping with German soldiers. L'épuration sauvage, the French called it: the savage purification.

The facts in this case were not in question. They came from a seemingly unimpeachable source: Captain Louis Obrecht, an adjunct controller in the French military government and president of the local Purification Commission. Obrecht was a veteran of the French army and a former prisoner of war. When German forces invaded Alsace in 1940, Obrecht was the school principal in the village of Bartenheim, where the prisoner later became Ortsgruppenleiter, or the town's Nazi Party chief. For four years, Obrecht insisted, the prisoner had been the terror of Bartenheim. "But it was above all in the last year of ‘his reign' that he became menacing and dangerous."

Obrecht went on to accuse the man of crimes ranging from sabotage to using French children as spies. But the investigators zeroed in on a single incident: the murder of a local farmer named Georges Baumann. On the morning of Wednesday, October 4, 1944, a German military police chief named Anton Acker ordered Baumann to report for a work detail, building wooden pallets for the German army. Baumann refused. The war had turned against Germany by then, and the Allies were on their way. He had no intention of working for "those German swine," he said. When Acker tried to arrest him, a scuffle ensued, and Baumann and his family disarmed the officer.

Their victory was short-lived. Within the hour, Acker returned with five other policemen. Baumann was arrested, as were his wife and daughter later that day, while his son fled into the fields. The three prisoners were taken to a police station, where they were detained and beaten. By that evening, Baumann lay half dead. "I found him on the floor of the station, unconscious, his hair, cheeks, and forehead covered in blood," a local doctor later told investigators. "His scalp was split open, without a doubt from blows of a rifle butt, and he also had a bullet wound in his pelvis, with tears in his intestines and probably an artery as well." Baumann died in the hospital that night. By then, bruises from the bludgeoning had begun to appear all over his body.

The death of Georges Baumann could be traced back to one man, Obrecht believed. It was set in motion by a direct order from the prisoner in the interrogation room. "For four years, he made thousands of innocent people suffer," Obrecht said, and the inspectors had no reason to doubt him. The war had been over for nearly a year and fresh horrors were still being unearthed in mass graves and killing fields and concentration camps across Europe. There was more than enough guilt to go around.

Yet the inspectors had also heard rumors of a different sort. There was talk that this gaunt, bespectacled bureaucrat-this "perfect Nazi," as some people described him-was the opposite of what Obrecht claimed. That far from terrorizing two villages, he had shielded them from the worst Nazi excesses during the occupation. That withou...

Suspect

The man in the interrogation room had all the marks of a dangerous fanatic: stiff spine and bony shoulders, lips pinched into a pleat. He wore brass spectacles with round, tortoiseshell rims and his head was shaved along the back and sides, leaving a shock of brown hair to flop around on top, like a toupee. When he posed for his mug shot, his expression was strangely unbalanced. The left eye had a flat, unwavering focus, edged with fear or grief. The right eye was glazed and lifeless.

The French inspector, Otto Baumgartner, paced in front of him reading from a typewritten sheet. "In October of 1940, you moved to Alsace and set yourself the task of converting the inhabitants of Bartenheim to National Socialism," he began. "You established yourself as Ortsgruppenleiter in order to become the town's absolute master. . . . You brought to your duties a zeal and a tyrannical fervor without equal! In the entire district of Mulhouse, you were the most feared and infamous of leaders!"

Baumgartner paused after each charge to let the prisoner respond, while another inspector transcribed the exchange. It had been nearly a year since the German surrender, and these men had heard their share of pleas and denunciations. The countryside seethed with military courts and citizens' militias, lynch mobs and makeshift tribunals. For four years, the Nazi occupation had divided France ever more bitterly against itself, turning neighbor against neighbor and Christian against Jew. Now the days of reckoning had come. More than nine thousand people would be executed as war criminals and collaborators over the next five years, in addition to those denounced and beaten; the women shorn and shaved and paraded through towns for sleeping with German soldiers. L'épuration sauvage, the French called it: the savage purification.

The facts in this case were not in question. They came from a seemingly unimpeachable source: Captain Louis Obrecht, an adjunct controller in the French military government and president of the local Purification Commission. Obrecht was a veteran of the French army and a former prisoner of war. When German forces invaded Alsace in 1940, Obrecht was the school principal in the village of Bartenheim, where the prisoner later became Ortsgruppenleiter, or the town's Nazi Party chief. For four years, Obrecht insisted, the prisoner had been the terror of Bartenheim. "But it was above all in the last year of ‘his reign' that he became menacing and dangerous."

Obrecht went on to accuse the man of crimes ranging from sabotage to using French children as spies. But the investigators zeroed in on a single incident: the murder of a local farmer named Georges Baumann. On the morning of Wednesday, October 4, 1944, a German military police chief named Anton Acker ordered Baumann to report for a work detail, building wooden pallets for the German army. Baumann refused. The war had turned against Germany by then, and the Allies were on their way. He had no intention of working for "those German swine," he said. When Acker tried to arrest him, a scuffle ensued, and Baumann and his family disarmed the officer.

Their victory was short-lived. Within the hour, Acker returned with five other policemen. Baumann was arrested, as were his wife and daughter later that day, while his son fled into the fields. The three prisoners were taken to a police station, where they were detained and beaten. By that evening, Baumann lay half dead. "I found him on the floor of the station, unconscious, his hair, cheeks, and forehead covered in blood," a local doctor later told investigators. "His scalp was split open, without a doubt from blows of a rifle butt, and he also had a bullet wound in his pelvis, with tears in his intestines and probably an artery as well." Baumann died in the hospital that night. By then, bruises from the bludgeoning had begun to appear all over his body.

The death of Georges Baumann could be traced back to one man, Obrecht believed. It was set in motion by a direct order from the prisoner in the interrogation room. "For four years, he made thousands of innocent people suffer," Obrecht said, and the inspectors had no reason to doubt him. The war had been over for nearly a year and fresh horrors were still being unearthed in mass graves and killing fields and concentration camps across Europe. There was more than enough guilt to go around.

Yet the inspectors had also heard rumors of a different sort. There was talk that this gaunt, bespectacled bureaucrat-this "perfect Nazi," as some people described him-was the opposite of what Obrecht claimed. That far from terrorizing two villages, he had shielded them from the worst Nazi excesses during the occupation. That withou...